Review: Maquia – When the Promised Flower Blooms

Mari Okada’s directorial debut successfully merges high fantasy with a multigenerational family drama

The queen of emotionally charged anime screenplays, Mari Okada, has graduated to director. At first glance, her debut, Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms (now at the tail end of its limited US theatrical run), seems a little outside her wheelhouse — it has a Western high fantasy aesthetic, a far cry from the modern Japanese settings of series like Anohana and Hanasaku Iroha. But its narrative core is pure Okada: raw emotions explode between characters in indulgent “cry jam sessions” (as my podcast co-host David is fond of saying), and yes, sometimes the script is a little corny and on the nose. Nevertheless, it’s an ambitious, visually stunning, and (dare I say) moving exploration of love and family.

The fantasy world of Maquia has no elves or dwarves, but its closest equivalent are the Iorph, a race of blonde-haired mystics who live for hundreds of years and weave their life stories into cloth. When the nearby kingdom sends soldiers to pillage the Iorph’s homeland and kidnap their women, the 15-year-old Maquia manages to escape, but finds herself adrift in the mortal world with not a cent to her name. What keeps her going is the abandoned human baby she finds in the woods; she’s determined to be a good mother to him, though he will age and die while she will look exactly the same for centuries.

That conflict, Maquia’s struggle to protect and care for her son despite their unique and precarious situation, forms the bedrock of the story, and it’s impressive how much mileage the film gets out of it. Maquia’s uncertain embrace of motherhood is placed against the backdrop of roughly four different subplots all revolving around mothers and their children. One strong-willed human mother raises her two boys alone on a farm. A member of the Iorph is kidnapped and made to bear children for the prince, but spends her life locked away from her own daughter. And as the film goes on, it even crosses generations, making a statement about the marks we leave on the world through the relationships we build and the stories we tell.

Running through it all is Okada’s unfortunate tendency for melodrama, but in the fantasy setting, this particular proclivity feels surprisingly at home. In a larger-than-life world of dragons and near-immortal beings, there’s a sense that Okada finally has the emotional breathing room she needs for the kind of intensity she’s so fond of. A scene where Maquia and her son bury a dog feels blatantly manipulative at first, but it’s used as the basis of a heart-wrenching scene where it dawns on Maquia that she will one day have to bury her own short-lived son. It’s the kind of cosmic tragedy that would be literally impossible in a more realistic film.

This dovetails nicely with a parallel theme about living life to the fullest. The Iorph come from a culture of stability and unity, but in their exile they find themselves on different paths. Some choose, as Maquia does, to build a new life disconnected from their past. Others try to recreate everything that they lost. Still others get no choice at all, and find themselves exploited and discarded by their imperialist masters. The message at the end of it all isn’t particularly novel, but there’s a remarkable clarity and sincerity to it. It’s not hard to connect these stories of parents and children, immigrants and exiles to both our own personal lives and the politics of our times.

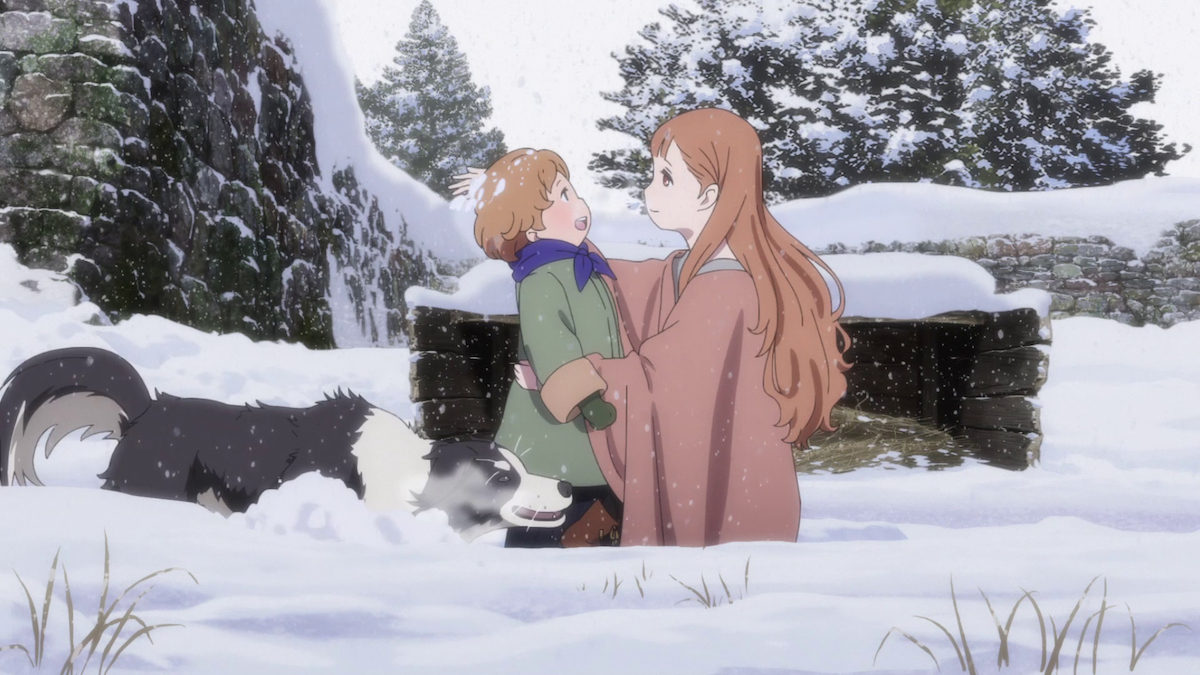

Then there’s the visuals. P.A. Works are already known for the attention to detail in their productions, but Maquia might be some of their best work yet. The backgrounds from Kazuki Higashiji (Hanasaku Iroha, A Lull in the Sea) do a great job establishing the varied fantasy locations of the film — they’re beautifully textured and have a crispness that has become the trademark of background studio Bamboo.

The character animation, led by legendary animator Toshiyuki Inoue (Akira, Kiki’s Delivery Service), is full of charming moments of playfulness and vulnerability, whether it’s a little hand gesture while a character is talking or a subtle expression that plays across their face. At times Maquia’s doe-eyed fifteen-year-old design feels a bit too close to the cloying sweetness of Kyoto Animation, but the script sends her to such heights of joy and depths of despair that she feels far more substantial than her looks would imply.

It’s hard to tell how much of the directing comes from Okada herself; while she’s credited as “Director,” Gainax vet and Yuri!!! on Ice character designer Tadashi Hiramatsu has the unusual title of “Core Director,” implying that he might have handled a lot of the day-to-day directorial duties. Either way, the pacing feels just right, leaving enough time for emotional moments to sink in without dwelling too long in any one scene or location. And though in our interview Okada said she tried not to focus too much on making directorial choices for the sake of making things beautiful, there are tons of sweeping vistas and establishing shots that show off Higashiji’s excellent background work.

In the past I’ve found Mari Okada’s emotional extremism tiring and self-indulgent, but Maquia has me genuinely impressed. It’s still very much the same Okada, and there are still the occasional eye roll-inducing bawling sessions and emotional telegraphing. But the setting and themes speak to something far beyond high school angst and first loves, and deliver moments of profound pain and exquisite beauty.