Ever have just a little too much to drink and, due to the kindness or mischief of friends, wake up in some other place than you remember being last? Well, I have to give a big thanks to Evan Minto here at Ani-Gamers for giving Drunken Otaku, a silly drinking-based anime blog I started during the Ani-Gamers lull, a new home as a regular column! You’ll still be exposed to the Great Drinkers (profiles), Great Moments in Drinking (more or less), and Beer Goggles (reviews) you may have come to love, but you’ll see them in a much more … blue … environment and on a regular schedule (once a month, blackouts permitting). House Rules still apply, so with those in mind: kanpai!

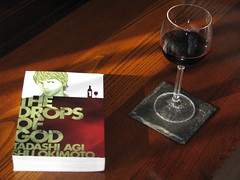

Varietal: Seinen Manga (Chapters 1-18)

Vinter: Tadashi Agi (Yuko & Shin Kibayashi)

Label Artist: Shu Okimoto

Sommelier: Vertical, Inc. (US)

Cellar: Weekly Morning (JP)

Vintage: November 2004 – Present (JP)

Age Rating: 21+ (or younger with convincing fake I.D.)

Created and written by a brother-sister pair using the pseudonym Tadashi Agi and illustrated by Shu Okimoto, The Drops of God follows Taiyo Beer salesman Kanzaki Shizuku as he tries to prove himself the rightful inheritor of his late father’s estate: a mansion with a wine cellar worth roughly two billion yen. Shizuku’s father, Kanzaki Yutaka, was a world-renowned wine critic and collector who devoted what seems to be the entirety of the time spent with his son to delivering an intricate education on the ways of the vine. Like most children force-fed any kind of topic, Shizuku rejects wine due to the fervor of his father’s obsession (thus the job at Taiyo Beer) and really couldn’t care less about the inheritance … that is until it’s contested by one Tomine Issei. One week before Shizuku’s father passed, Issei, a celebrated wine critic, was adopted as Yutaka’s son. To determine which of Yutaka’s sons will inherit the estate, Shizuku and Issei have to describe, in the same descriptive vein of their father, the essence of 13 specific bottles of wine within one year’s time via blind taste tests.

While the plot is certainly centered around the struggle between Shizuku and Issei, the real struggle of the story is the exploration of self through which Shizuku has to go in order to be able to relate to his late father. Shizuku has had an in-depth education on the ways of wine but has never drank any, putting him at a severe disadvantage at a blind tasting. Issei has had a lifetime and celebrated career as a wine taster, but only one week as Yutaka’s son. As the plot progresses, Issei doesn’t try to be any more a son to the departed, but Shizuku (with help from apprentice sommelier Shinohara Miyabi) goes through various trials that bring him further and further down into the cellar of the subject that was his father’s passion.

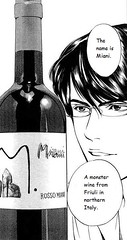

The aforementioned trials are the bulk of this manga, and the wines they center around (all 100% authentic) are the respective heft of the chapters. This is made most obvious via the attention paid to the visual rendering of any panel featuring bottles or wine. Character designs and settings are distinguished but rather average in most instances, while any scene involving wine, wine bottles, or the various visual metaphors employed for the euphoric experience of tasting wine (a Queen concert, a maiden in a field, a merry-go-round, a scene from Strauss’s Salome) come across not as photorealistic but as lovingly crafted portraiture. Any serious wine drinker will love this manga for this aspect alone. To all readers, the alternation betwixt what I’ll call character and bottle style imbues this 424-page volume with a diversity of visuals that whets appetites for the next feast.

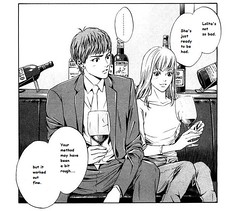

There is also a LOT of textual description within these pages: vinter lineages, wine taste, wine smell, how to drink wine, how to pour wine, when to pour wine, wine origin and similarity … you get the gist. Casual readers would probably find the material a bit too dry for their tastes were it not for the almost beguiling charm derived from the pacing of Shizuku and Miyabi’s adventures as well as humor written a little too perfectly via extended metaphors exploiting similarities in terminology between manga and wine (such as the conversation pictured on the right). So that, combined with the almost laughably yet convincingly applied left-field taste analogies (did I mention the Queen concert?) and their culmination, actually makes the manga a proverbial page-turner. The same characteristics contribute to readability for those in the know. Being shoveled information on decanting, vintages, vineyards, etc. can be downright tedious, but it is the mix of storytelling techniques and art that will elicit interest and propel wine connoisseurs through the book. While outright descriptions attempt to fill readers in on the wines as well as the experience of drinking them, the authors and illustrator do a fantastic job defining Shizuku and Issei via glimpses into their preparations for the upcoming battles.

Shizuku, whose first musical wine metaphor involves Queen, describes the wine admiringly as “somehow like classical” but not quite, with “a melting sweetness and a sharp rush of sourness.” Altogether not the most poignant of descriptions, but it is a Romantic one. Later on, readers get a taste of Issei’s musical leanings: Richard Strauss’s opera, Salome, which Issei associates with a “blood scented sensuality born of decadence.” If one sets aside the obvious sweet vs. evil leanings of those descriptions, the context in which they are delivered is as subtle delivery mechanism as any for showing a major difference between the main characters.

The perpetual learner, Shizuku mostly listens to others. When he does speak, usually to elaborate upon the characteristics of a wine at hand or demonstrate a wine-related technique, his flowery meditations are written such that they are more Zen moments of sensory exploration that seem identifiable to those surrounding Shizuku. Even the way he gives advice to people shows him to be a genuine helping hand — a person who keeps in mind exactly who he is reaching out to as opposed to showing off transcendent talent of taste/technique. The latter is more applicable to Issei’s preachy tone. A lecturer at heart, Issei often talks as though no one else is in the room … even when it’s part of a dialogue. I wager readers can take everyone else out of a scene involving Issei describing wine and that scene would have the same effect. By the end of the volume, the main characters’ choices of musical allusions reflect not only how personable they are but their sense of modernity as well. So far, Shizuku involves the recent present (as much as 70s Queen is recent) and Issei invokes a century-old opera. As wine is consistently referred to as a living thing (temperamental), how closely each critic can pull similarities from their own near history is an indication of who keeps wine closer and who put it upon a pedestal of distance.

Not everything in The Drops of God is great. The pacing can seem laborious depending on personal experience with and interest in wine, and there are a few minor instances where clichés border on offensive and overly convenient: why must the wine wisdom and saving grace in one arc come from a homeless person … who then ends up knowing the main characters and acting as a judge?! But even if I found myself getting angry at situations like that, keep in mind that I was getting angry because it wasn’t perfect. Why? Because this manga is just that good, and I wanted it to be perfect. This graphic novel has actually influenced countries’ wine sales and purchases fer chris’ sake. If nothing else, to quote Evan Minto, “it’s almost frustrating how compelling it is!”