I Can't Stop Lovin' You

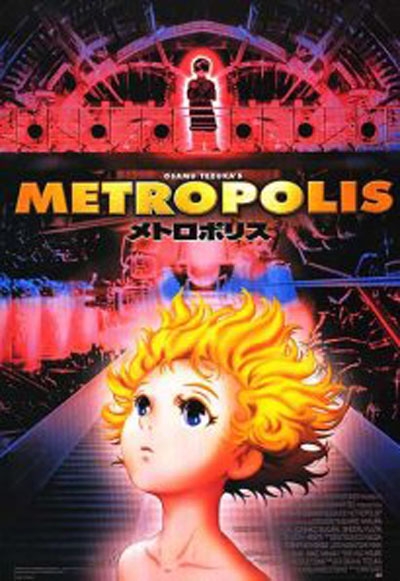

<cite>Metropolis</cite> (2001)

It’s nice to rediscover a classic that you liked only to find that you love it the second time around. I’ve owned the 2001 animated version of Osamu Tezuka’s Metropolis for the better part of a decade now but I’ve not watched it for the same amount of time. Finding it on Netflix, I was curious to see if it still held up. Directed by Rintaro and written by Katsuhiro Otomo, the film is both a departure from and reaffirmation of the original manga and the sci-fi classic from which it takes its inspiration.

It’s nice to rediscover a classic that you liked only to find that you love it the second time around. I’ve owned the 2001 animated version of Osamu Tezuka’s Metropolis for the better part of a decade now but I’ve not watched it for the same amount of time. Finding it on Netflix, I was curious to see if it still held up. Directed by Rintaro and written by Katsuhiro Otomo, the film is both a departure from and reaffirmation of the original manga and the sci-fi classic from which it takes its inspiration.

Set in the future city of Metropolis, the story revolves around the construction of an enormous Ziggurat—a multi level mega-skyscraper, built and under the control of the ruling alpha oligarch, Duke Red, who is shadowed and helped by his adopted heir, Rock, along with the Marduke Party (Duke Red is financially supporting them and is the defacto leader). On the surface, the people celebrate this magnificent marvel of engineering, but below the surface, even during the Mayor’s speech during the opening of the building, tensions are reaching a boiling point. Ostensibly, the main problem which lives below in Zone 3, the lowest level of the city, is a simmering resentment on the part of the working class humans—those who are so unwanted that machines and robots have completely assumed their purpose in Metropolis. Couple that with the fact that the machines themselves are starting to resent that they can’t go into certain areas of the city and are trodden on by their masters and shot in the streets and alleys like dogs, and things are not as rosy as they appear. Detective Shinsaku Ban arrives in Metropolis on the night of the dedication of the Ziggurat along with his nephew, Kenichi, tracking the illegal activities of Dr. Laughton, a robotics expert with an amoral streak. Of course, Laughton is in the employment of Duke Red building a robot girl named Tima. Tima is special in ways that only Laughton and Duke Red know. Rock, following his father, fatally shoots Laughton and tries to kill Tima and destroy Laughton’s lab before she can awaken. Before he can, a crowd gathers, including Ban, Kenichi, and their robotic Pero, and Rock retreats into the shadows. Kenichi finds Tima after Ban finds Laughton. Now everyone is either trying to find out the truth behind Tima’s existence or trying to bury it. The stage is set.

Words don’t do Metropolis justice as a cinematic tour de force. At its heart is a fundamental choice to stand up for the decency of the human spirit. The human workforce is being treated poorly, and while the more desperate elements would love nothing more than to burn it all to the ground, there are people who just want a measure of dignity. Far from the glamour of the alabaster towers, the people can only look up at the sunlight and dream of a better life. The robots are happy to work the truly terrible jobs they are given, but the sheer contempt they are held in by their creators makes their existence hell. Rock is the ultimate expression of the paranoia and fear of humankind toward their own creations. He dispassionately murders them in the street as vermin, all in the hope of his “father’s” approval. Duke Red is a man driven mad with grief and consumed with the need to control everything in his eminent domain. This need to replace what he has lost causes him to alienate a boy, Rock, who genuinely loves him and sets him on a path that will destroy his enemies, his allies, and innocent people alike. Shinsaku Ban is the pure, distilled essence of the practical gumshoe: he always gets his man, sees the evil that men do and laments that he cannot do more, and does what is required that justice might prevail. Central to the story is Kenichi and Tima and how Kenichi finds out just how far he will go to save the girl he just met. Tima doesn’t deserve the reason for which she was created, but she has the full treatment as a robot that learns the awesome and terrible truth behind choosing between life and death. As she grows as a person, Tima gently breaks free from Kenichi and becomes a being in her own right. All these people are going to collide, and every hope, dream, madness, fear, impulse, and self-destructive feeling is heading their way.

The film also introduces a serious power struggle between the Mayor, the President, and Duke Red. Red’s building something awesome and evil atop the Ziggurat, and the Mayor and President of Metropolis are scared witless of it. They think they can outsmart Duke Red and still maintain a mask of civility. Little do they realize that Duke Red is not just worrying about the political fallout from the outside world but them as well. As the film works its way to the end, the elements of the original 1929 Fritz Lang version are worked into the fabric: the workers revolution, the oligarch’s need to wipe out dissent, and the simple robot becoming a great and terrible axe to sweep over the people of Metropolis. After reading the original manga by Tezuka, from which he claimed he took only the basic idea and the still image of Maria the robot from the original film, I can understand why Otomo chose the elements he did to use in the update. The original would have made an interesting long form series but not a very good film. By fusing both films together, Rintaro and Otomo allow Tezuka’s world to shape events but not the characters.

The art and direction on show—with an emphasis on vast, open areas and shots of characters lost in the sprawling city—is superb. The down-below of the lower Zones is a shantytown of cobbled shacks, disorganized alleys, loading docks, and warehouses where the unobserved and unseen proletariat meet in secret commune. Zone 2 is where the robots live automated and regulated lives and humans seldom tread. All the dangerous energies and substances that no flesh-and-blood creature could handle are innocently and faithfully dealt with by the machines. Here, deals are made in secret and obsessive bodyguards hunt down innocents against a neo-noir, industrial design nightmare. Zone 1 is the light, the ideal and cause of all jealousies in Metropolis. It’s a fan of Art Deco’s Shangri-La: huge German style halls, stations, and buildings and Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired air corridors and building-spanning domes. Here, mansions set atop buildings with greedy and expectant eyes turn upward to the Ziggurat which dominates even in this rarified air. Rintaro takes the time to show his cast caught in these places in misé-en-scene where the background, crowds, sounds, shapes, and colors all blur so that viewers see only the person in the scene with a purpose and dialog. Each crowd scene, lovingly, has individual character designs so that no two crowd members are the same. The same attention to detail makes characters like Fifi the robot, who looks the same as other robot models, stand out because of damage, patina colouring, and personality traits. These distinguishing aspects all serve to bring the performance out from behind the neat visuals. Rintaro also adds Twenties-style scene wipes that shrink circles on a point of action and reopen in the same scene at a later moment.

The cast in both languages (Japanese and English) nail their characters, and I’m happy to see people like Barbara Goodson, Rebecca Forstadt, Steve Blum, and Doug Stone heading the English cast while Kōsei Tomita, Norio Wakamoto, and Taro Ishida give the original audio everything to keep the audience there and in the moment. I still grin when Duke Red approaches his podium at the start of the film, gives a speech, and therein proclaims “May it stand forever! Our Ziggurat!!” to start the story.

Finally, the score by Toshiyuki Honda seals the deal as the universal nature of the film and the correct balance between the past versions of Metropolis and this latest incarnation. A mixture of Jazz and Dixieland, the Roaring Twenties, is the DNA of Metropolis’ aural experience. The feel of depression and listless nature of life in “Going To “Zone” and “El Bombero” smashes over your ears as people run across halls, streets, and squares to meet the latest crisis. Somber and eloquent tracks like “Sympathy” flesh out a more orchestral view throughout the film. A rendition of “St James Infirmary” allows Rintaro to show Tima how far from the light she is. Finally, I get emotional every time I hear “There’ll Never Be Goodbye”, the ending theme of the film. It’s so jazzy, so sad and filled with the memories of people and loves long gone but not forgotten. It’s the capstone for the whole endeavour. In fact, the only way to survive the ending is to listen to the other ending song: Ray Charles’ “I Can’t Stop Loving You.” Both themes are Kenichi and Tima’s theme. It’s up to you which suits them better. Here’s a link to the soundtrack for you to enjoy.

Apparently, there is a final moment at the end of the credits in the Japanese blu ray release and the original theatrical version where the formal ending is not as final as we are led to believe. If that’s the case, then the film’s creators really have gotten the mix of anime and German Expressionist films right. I’m just annoyed that the US/UK DVD omits this ending. In an interview on the DVD I have somewhere around here, Rintaro and Otomo both agree that Tezuka would not have OK’d Metropolis as an animated project. I would hope they meant that he would have not have chosen to do the original manga, as the film stands as an amazing tribute to Dr. Tezuka and to animated filmmaking in general. A visual treat, a compelling, if oft-repeated, story, and a brilliant ending, the film not only escapes the Trap Door, it flies out to find more people to enjoy it.

On the 25th of every month in “The Trap Door,” Phillip O’Connor tackles one forgotten anime title to find out whether it deserves to be rediscovered by the anime community. Click here to check out previous entries in the column.