Getting In, Getting Out

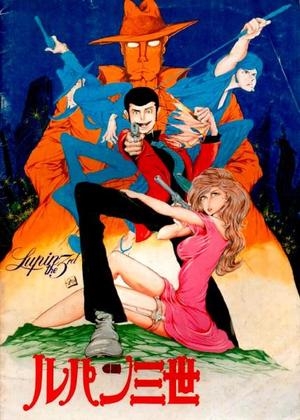

<i>Lupin III: The Secret of Mamo</i> (1978)

Hi all! Welcome to my new column, “The Trap Door,” where I hope to explore the titles that have been released to little fanfare, gotten old, or gone out of print. Some I will have watched before and some I’ll only have heard of once or twice. In The Trap Door, I want to communicate my personal thoughts on titles, rather than speak about whether or not they are necessarily “good” or “bad.” I want to see where they sit in the great hallways of media we find ourselves in these days. Do they deserve to escape the trap door that audiences have dropped them into, or should they remain there, imprisioned and forgotten? Now, just so you know, I won’t be covering evergreen titles like Neon Genesis Evangelion or Dragonball Z. They keep being reprinted so they don’t count in my book. Not every title will be available from places like Amazon, Best Buy, Barnes & Noble, or Right Stuf (but I will try and put links up where I find them). Right, with that in mind, let’s do this!

Hi all! Welcome to my new column, “The Trap Door,” where I hope to explore the titles that have been released to little fanfare, gotten old, or gone out of print. Some I will have watched before and some I’ll only have heard of once or twice. In The Trap Door, I want to communicate my personal thoughts on titles, rather than speak about whether or not they are necessarily “good” or “bad.” I want to see where they sit in the great hallways of media we find ourselves in these days. Do they deserve to escape the trap door that audiences have dropped them into, or should they remain there, imprisioned and forgotten? Now, just so you know, I won’t be covering evergreen titles like Neon Genesis Evangelion or Dragonball Z. They keep being reprinted so they don’t count in my book. Not every title will be available from places like Amazon, Best Buy, Barnes & Noble, or Right Stuf (but I will try and put links up where I find them). Right, with that in mind, let’s do this!

Lupin III: The Secret of Mamo (or the Mystery of Mamo in some territories) was released theatrically in 1978 and is one of the Lupin III films as opposed to one of the myriad specials or TV series. How does it differ from the rest? Couldn’t tell you, I haven’t have the foggiest; my experience with Lupin consists only of this and The Castle of Cagliostro. So why include this in The Trap Door? Well, I have to tackle what I feel is a neglected title, and I see no love for Mamo. And it really is a blast. Imagine if you will, a James Bond movie where the villain’s right-hand man is the main character, they aren’t that villainous, and they stay badass. This is Lupin for me. Created by manga artist Monkey Punch (Kazuhiko Katō) in 1968, Lupin III — pronounced “Lupahn the Third” — is the grandson of famed fictional thief Arsene Lupin (which the estate of original Lupin creator Maurice Leblanc has never been happy with). In his exploits as the world’s greatest thief, he traverses the globe with his partners in crime: Jigen, gun master, and Goemon Ishikawa XIII (referred by all as simply Goemon), sword wielding warrior. Along the way, they frequently cross paths with Detective Zenigata (OF INTERPOL!!!) and, of course, team up with or find themselves in competition with beautiful fellow thief Fujiko.

Also, from a scriptwriting angle, having Lupin die in the opening moments and then be alive five minutes later sets up a payoff that I didn’t fully expect them to pay out. Some writers do remember to go back to that sort of thing and others just say “Oh, sugar! I forgot I used that idea at the start! Quick, Courier font! Stat!” Mamo pays off with this subplot at the halfway point and repeats the payoff again at the end. Am I reading too much into this? Possibly, but at least this comes from an era in filmmaking when writers and directors worried how their audiences would interpret their choices in character and plot arcs.

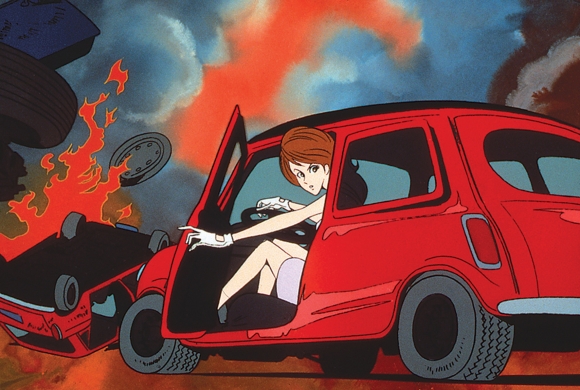

Returning to the film, it’s interesting that this movie introduces Fujiko being buck-ass naked. Contrast how Miyazaki portrays Fujiko in Castle Of Cagliostro and you can begin to see my confusion as to which tone is correct. (I’ve been told that the way Lupin is portrayed in the manga and how it’s portrayed in the moving image version are totally different.) So, is the Fujiko in this movie an undervalued and over-sexualized character? Well, yes and no. We constantly see her in either a state of undress or being hit on by Lupin. I know Lupin really likes Fujiko, despite the amount of times she casually betrays him, but this movie shows Lupin being both sleazy and gentlemanly toward her. Watch as he breaks into a locked room in nothing but underwear looking for a semi-naked Fujiko. (Hint: It isn’t to ask her would she like a cup of tea.) Then as the plot unravels around them, watch as he protects Fujiko again and again from Mamo, going to the ends of the earth to get her. It’s a strange law of extremes on display here. But a quick glance at Wikipedia tells me the writing duties were handled by director Soji Yoshikawa and Atsushi Yamatoya. The latter is known for writing and directing pink films, racy Japanese films popular in the 60’s. C’mon, his credits include Alleycat Rock: Female Boss, Banned Book: Flesh Futon and Inflatable Sex Doll of the Wastelands! I dare you to say he was the more conservative one on the Lupin writing team!

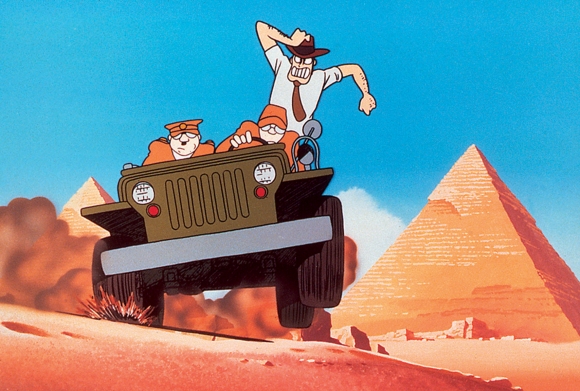

I like Lupin himself, and I suspect they’d have to do a radical overhaul of the character for me not to like him. He’s got that lust for life. Robbing people and institutions blind is fun and all, but for Lupin it’s the thrill — the chase — that’s more exciting. Take the opening of the movie. Detective Zenigata has Lupin and Jigen cornered in a pyramid (Cornered? Pyramid? Get it? Huh? Huh?), and Zenigata is going crazy directing the Egyptian police all over the site trying get Lupin. Does this bother our boy? Nope, he takes it in stride. On a motorcycle. And down a rope. While on a motorcycle. I think if Lupin were on his own with no Jigen and no Goeman, he’d probably get along fine. But if there were no Zenigata, or Fujiko for that matter, then his life would have no meaning.

And at this stage in their respective careers, Lupin and Zenigata know each other too well. Zenigata never believes that Lupin has died. Without missing a beat, he goes to a castle straight out of Dracula to find Lupin. Lupin escapes but then he can anticipate Zenigata’s every move, and for his part, the detective has started to plan for every eventuality. The threat posed by a good villain causes heroes to up their game and in Mamo, Lupin has a ball fighting with the title character. A diminutive man, Mamo’s strength as a character lies in his absolute belief that he is THE most important player on this stage. Whether it’s ordering the indiscriminate killing of helpless people to get Lupin or threatening the US President, it’s all in a day’s work for our resident madman. At the end, you’re still not certain what Mamo is, even after all the speeches, exposition and tricks. That’s a good villain.

Speaking generally of the film, the design work on display from art director Yukio Abe is amazing. From the streets of Paris to the wastes of Spain, from the towns of Columbia to Mamo’s invincible fortress island, it’s all amazing. This isn’t a Ghibli level of detail, but it’s really good nevertheless. I especially like the details in the café scene, where a machine gun-toting helicopter descends just to kill Lupin and co. All hell breaks loose. People die, bullets fly, and cars explode in elaborate slo-mo. Plus Jigen keeps the same amount of wine in his glass while running away from the mayhem. It’s a cornucopia of movement and sound. Equally impressive, even if we don’t get to see it for long, is Mamo’s fortress. On the surface, it’s an elegant affair, but underground, it’s a maze of Roman and Greek gardens and architecture, high arch corridors, tubes, hatches, machinery, labs and endless rooms. But the things I notice are the little touches here and there, like the enormous truck sent to kill Lupin, Goemon, and Jigen, or Zenigata trying to prove Lupin is alive by digging him out of a castle crypt and driving a stake through his heart. How about the chase in Mamo’s pad through famous paintings and works of art? Why, you ask? Why the hell not? Whereas Castle of Cagliostro had lots of deliberate action with continuous movement, Mamo goes for kinetic movement and reused animations for fast character actions, leaving long panning and tracking shots for the quiet moments.

The music is fantastic. It really does embody the ’70s funk movement, with Yuji Ohno turning in a great score. I don’t think (with a few exceptions) a lot of anime utilizes music to its full potential. Certainly TV anime suffers the music seeing it’s usually part paid for by the Japanese record companies (thus lots of J-Pop music). But composers like Joe Hisaishi (Miyazaki’s composer of choice) or Susumu Hirasawa (composer for the late Satoshi Kon) shine in theatrical presentations, and Ohno gives it his all for Lupin. It stands in complete contrast to his work on Cagliostro.

I’m not going to write much about the voice cast in case I go into review territory. There are three dubs for this thing, not counting the Toho-produced dub (no credits exist for that dub save that voice acting legend Peter Fernandez worked on it). First Streamline tried their hand and had stalwarts like Bob Bergen, Steve Bulen, and Kirk Thornton as Lupin, Jigen, and Goemon, with Robotech alumnus Edie Mirman taking on Fujiko. Next, Manga UK (back when they were dubbing all their stuff in the high tech environs of Cardiff in Wales) had William Dufris, Eric Meyers, and Garrick Hagon in the roles stated above. Interestingly, Fujiko in this version was tackled by Press Gang actress Toni Barry, who I remember from that show and that other roles with Manga such as Project A-Ko, Dangaioh, and Dominion Tank Police, where she played my beloved Leona Osaki. Finally, dearly departed Geneon commissioned a dub featuring Tony Oliver, Lex Lang, and Richard Epcar as Lupin, Goemon, and Jigen. Michelle Ruff played Fujiko. As an aside, other than the late Yasuo Yamada as Lupin, everybody playing our heroes in Japanese is still doing the same roles TO THIS DAY. Talk about job security!

All in all, there’s enough here to save Secret of Mamo from being forgotten. Even if you disconnect the film from the franchise, it’s a good old-fashioned romp through Europe, the Pacific, and South America as our heroes fire guns, blow stuff up and generally make a mess of the local populations’ tranquility. For that reason, it gets to escape from The Trap Door.

(Hey, with the Lupin 40th anniversary celebrations just around the corner, check out Amazon UK for a dirt-cheap copy of the film. Unfortunately, the US version is significantly more expensive.)