Review: Your Name (Kimi no Na wa)

Makoto Shinkai's ode to a generation is beautiful, if a bit overambitious.

Your Name (Kimi no Na wa in Japan) is the biggest hit anime in years, landing just behind Disney’s Frozen in the ranking of highest-grossing films in Japan. It’s not hard to see why the movie has brought such massive audiences to the cinemas. Director Makoto Shinkai (5 Centimeters Per Second, Voices of a Distant Star, The Garden of Words) has a knack for incredible set design and intimate portrayals of human emotion, and he brings all of this to bear while shaving off some of the idiosyncrasies of his previous indie work. For newcomers to the director, Your Name is no doubt a spectacular, revelatory experience. For some of us who have seen what he is capable of, the movie can feel paradoxically both unfocused and overly simplistic.

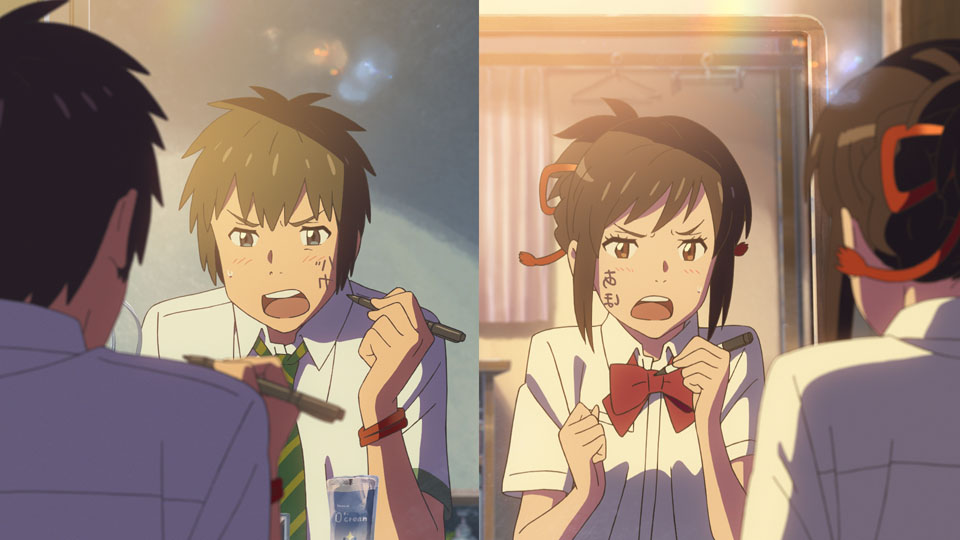

In a sense, Your Name is a typical Shinkai movie, but in reverse. The leads — bored country girl Mitsuha and city boy Taki — begin the story physically separated, but soon find that they inhabit each other’s bodies during their dreams. What starts as a curious supernatural phenomenon soon turns into a stressful tug-of-war between the teenagers, as each tries to prevent the other from inadvertently ruining their life. But it’s the second and third acts of Your Name that transform it from a quirky supernatural comedy to something more profound. The romance that develops between Mitsuha and Taki hits a snag, and they must overcome both a horrific catastrophe and time itself in order to close the gap between them, all while trying to hold onto memories of each other that seem to slip from their fingers like half-remembered dreams.

Your Name is brimming with unique, interesting ideas, especially considering how often Shinkai’s prior films rehash the same old story about star-crossed lovers. There’s body-swapping, spirituality, mortal danger, an exploration of gender identity, and a lot of quite funny character-based comedy (the kids coming to terms with their new body parts is especially charming).

But Shinkai is a creature of habit, and Your Name suffers when he falls back into patterns from his prior films. Characters retread lines almost literally (“I’ll search for you no matter where you go” or something to that effect), while Shinkai’s shot composition and background design similarly cribs from specific scenes in 5 Centimeters Per Second and Children Who Chase Lost Voices. The final sequence itself is a near shot-for-shot retread of another Shinkai film (I won’t spoil which), but with a far less nuanced ending. The worst is the director’s penchant for music video-style montage sequences. Your Name features no fewer than three of them, including an incongruous TV anime-esque opening song, and they often feel like a crutch for when Shinkai (also the writer of Your Name) can’t figure out how to move his characters into place for the next scene. In his previous films these sequences provided punchy emotional climaxes, however schmaltzy they sometimes were. In Your Name this tendency becomes distracting and serves only to confuse the story’s pacing.

On top of this, Your Name‘s three acts feature such radically different conflicts that the movie sometimes feels disjointed. Children Who Chase Lost Voices suffered a similar problem of being overburdened with too many different ideas, while 5 Centimeters Per Second avoids the problem entirely by simply presenting three separate short films. In Your Name there’s a binding thread between the three acts, but the momentum isn’t strong enough; I found it hard to stay totally invested all the way through. I was surprised to hear how many attendees at my screening were moved to tears by the end of the movie. Despite 5 Centimeters Per Second routinely reducing me to a blubbering mess, my eyes remained completely dry for the duration of Your Name.

Shinkai has admitted that Your Name is inspired in part by the 3/11 earthquake and tsunami, and the latter half of the story spends a lot of time exploring Japan’s post-3/11 anxiety about natural disasters, the death of small towns, and the loss of traditional culture to urbanization. This commentary on contemporary Japanese society is easily the film’s most interesting theme (and clearly has been quite powerful for Japanese audiences), but foreign audiences may lose track of it under the weight of body-swap antics and Shinkai’s dogged focus on romance between the teenage leads. What’s left by the end is a love story that is sweet but surprisingly shallow, considering the many promising avenues it takes to get there.

Still, those Shinkai visuals never cease to amaze. He is rightly renowned for his vibrant, hyperreal color design and intricately researched locations, both of which are present in Your Name, but the new addition this time is in the realm of character design and animation. Veteran character designers and animation directors Masayoshi Tanaka (Anohana, Toradora) and Masashi Ando (Princess Mononoke, Paprika, A Letter to Momo) create expressive modern anime designs that burst with life when set in motion. The first act in particular explores a series of hilarious juxtapositions of Mitsuha and Taki’s feminine and masculine tendencies, using their body language in many cases to accentuate the comedy. Shinkai’s previous work features fairly flat character designs that rarely move in particularly inventive ways, which arguably grants even more of a spotlight to his evocative background work. In Your Name, the characters take center stage, sometimes overshadowing the backgrounds and provoking a nagging sense that something of the director’s delicate, introspective magic has been lost in the shuffle. On the bright side, the move toward animation also results in a fascinating (and positively un-Shinkai!) montage that eschews hyperrealism for surrealism via pencil animation and psychedelic color work.

All that is to say that Your Name is not a bad film by any measure. It’s a beautiful, ambitious piece of animation housing a supernatural adventure with a lot of heart, but a lack of thematic focus. For any other director this would be a career-defining triumph. For Makoto Shinkai it’s merely his major-label debut: a little too cloying and commercialized, but a massive hit and a suitable gateway to the indie work that forms its foundation.