Secret Santa Review: Shiki

I got a Gothic novel in my Secret Santa stocking!

I wanted to hate Shiki so badly. I’m almost as sick of vampires as I am of zombies due to their ubiquity and banality in movies and other media; nothing’s new, and nothing’s scary. There is certainly nothing new about what Shiki does. Its plot can be summed up in a sentence — vampires come to an unassuming rural village (Sotoba) — or even three words: villagers versus vampires. How this series goes about revealing its biting tale of bloodlust, however, is at the very least a refreshing return to atmospheric creature features.

I wanted to hate Shiki so badly. I’m almost as sick of vampires as I am of zombies due to their ubiquity and banality in movies and other media; nothing’s new, and nothing’s scary. There is certainly nothing new about what Shiki does. Its plot can be summed up in a sentence — vampires come to an unassuming rural village (Sotoba) — or even three words: villagers versus vampires. How this series goes about revealing its biting tale of bloodlust, however, is at the very least a refreshing return to atmospheric creature features.

At its most laudable, Shiki could be said to share elements with the Gothic novels of Romantic literature. This is not to say Shiki is classic or even that the classics were good (I still have not managed to make it through all of Dracula without falling asleep at each sitting), merely that the elements Shiki shares with such classic tales note a remarkable (for anime) return to honest-to-goodness storytelling in a sub-genre that’s had its essence exhausted by loli fetishism and gratuitous gore. The similarities to Gothic novels — “a general mood of decay, action that is dramatic and generally violent or otherwise disturbing, [and/or] loves that are destructively passionate” ↓ — are not surprising given that Shiki was itself first a novel by Fuyumi Ono.

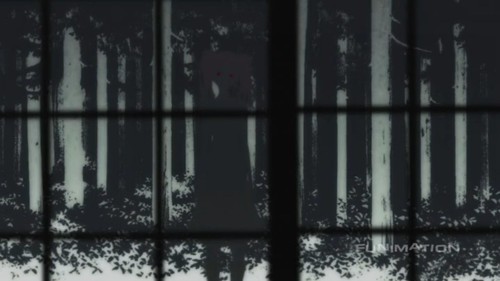

Believe it or not, Shiki‘s forte is its use of imagery to complement a script that’s not over-written and characters that, while not fully round, are far enough from static to be able to support inference and emotional subtext. In addition to the macabre — flies crawling on eyes and down throats to reveal death, decaying flesh of the deceased poised as if reaching out from shadows to relay desperation and anguish, and some quite frankly creepy foretelling dream sequences, there are often instances where everything is communicated visually. For instance, a ripped up postcard picked up solemnly, silently; the village’s slowly emptying streets and its subsequential increase in nightlife; transferred disgust and self-loathing via an emotional breakdown; and the slow decent into madness during the battle against one’s own nature via ever darkening eye-bags and facial stubble. These are but a few examples. Imagery is also used to tell stories within stories.

Believe it or not, Shiki‘s forte is its use of imagery to complement a script that’s not over-written and characters that, while not fully round, are far enough from static to be able to support inference and emotional subtext. In addition to the macabre — flies crawling on eyes and down throats to reveal death, decaying flesh of the deceased poised as if reaching out from shadows to relay desperation and anguish, and some quite frankly creepy foretelling dream sequences, there are often instances where everything is communicated visually. For instance, a ripped up postcard picked up solemnly, silently; the village’s slowly emptying streets and its subsequential increase in nightlife; transferred disgust and self-loathing via an emotional breakdown; and the slow decent into madness during the battle against one’s own nature via ever darkening eye-bags and facial stubble. These are but a few examples. Imagery is also used to tell stories within stories.

The most impressive use of imagery-based storytelling in this entire series, aside from the episode with the junior doctor’s wife, comes when villagers are spreading a warning from door to door. At one house, a woman refuses to open her door but sounds relieved that villagers are going to try and get rid of the monsters. She then turns around, the camera focuses on an old woman sobbing in front of a shrine, and the woman then says, “Mom … even if you’re starving, please bear it. Don’t attack anyone but me.” Behind the unanswered knock at the next house, the camera glimpses a precisely told story of death via a singular frame wherein the death-stilled arms of a starvation-stricken shiki woman sitting upright in a bathtub wrap around the hollowed corpse of a young boy in her lap. I could honestly go on for pages dissecting all the instances of creep, but there’s more to this series than that … like hair. So let’s go with that.

The most impressive use of imagery-based storytelling in this entire series, aside from the episode with the junior doctor’s wife, comes when villagers are spreading a warning from door to door. At one house, a woman refuses to open her door but sounds relieved that villagers are going to try and get rid of the monsters. She then turns around, the camera focuses on an old woman sobbing in front of a shrine, and the woman then says, “Mom … even if you’re starving, please bear it. Don’t attack anyone but me.” Behind the unanswered knock at the next house, the camera glimpses a precisely told story of death via a singular frame wherein the death-stilled arms of a starvation-stricken shiki woman sitting upright in a bathtub wrap around the hollowed corpse of a young boy in her lap. I could honestly go on for pages dissecting all the instances of creep, but there’s more to this series than that … like hair. So let’s go with that.

As silly as it may seem, the outrageous hairstyles in Shiki are very important – not important to the story but rather as a means of anime making a Gothic tale its own. As opposed to Le Portrait de Petite Cossette which goes full-on embodiment, Shiki makes a statement about anime’s adoption of these European horror phenomena. To put its own stamp on it, what better way than with something uniquely anime? What’s more uniquely anime than phosphorescent hair colors and gravity-defying ‘dos? Honestly, there are better ways, and the writing pretty much takes care of it. Even though its utterance seems laughable, there’s a very good reason why the castle known as Kanemasa is constantly referred to as that “European-style house” on the hill. And it’s notable that Kanemasa was built on top of an old house that was torn down. Early on, this architectural replacement implies the intentional application of old-school Gothic traditions instead of classic Japanese. Shiki furthers this via its villagers’ not-wrong-but-not-completely-correct identification of vampires as Okiagari — people who are dead and come back to life, a local superstition — and the creatures names (shiki or “corpse demon”) which come from a book being written by the junior monk based on the biblical story of Cain and Abel. Other cultural references infer an atmosphere of death, but none more so blatantly than the village’s name, which is that of wooden grave markers coincidentally made from trees surrounding the village. Get it — a village surrounded by death.

Shiki is not all doom and gloom. The series does throw in bits of humor (inappropriately at times) even if it is self-effacing and counterproductive. The thing I first noticed, aside from nominal jokes, was the haunting, child-like singing that backs character introductions. Well, viewers are introduced to just about every resident of the village (which provides for a variety of perspectives and focus), so some fun is had in the ways in which that creep is leveraged. There’s also the festive introduction to the Kanemasa residents, the shiki funeral parlor, and the villagers’ very humanistic personalities. One of said personalities, that of Masao Murasako, is nothing more than grating. The morality he displays can be found in other characters, and if he’s meant for comedic relief, then his presence is just a consistent fail.

Shiki is not all doom and gloom. The series does throw in bits of humor (inappropriately at times) even if it is self-effacing and counterproductive. The thing I first noticed, aside from nominal jokes, was the haunting, child-like singing that backs character introductions. Well, viewers are introduced to just about every resident of the village (which provides for a variety of perspectives and focus), so some fun is had in the ways in which that creep is leveraged. There’s also the festive introduction to the Kanemasa residents, the shiki funeral parlor, and the villagers’ very humanistic personalities. One of said personalities, that of Masao Murasako, is nothing more than grating. The morality he displays can be found in other characters, and if he’s meant for comedic relief, then his presence is just a consistent fail.

Other fails include certain instances of CG in dream sequences; needless time jumps; in-scene time slowing, stopping, rewinding, and fast-forwarding; and an almost medical otaku approach to describing symptoms of those afflicted by the shiki. While the latter works in well by using the focus of a medical professional to approach Shiki’s premise in a real-world manner, its drawn-out instances using over-the-top medical jargon can easily make the audience phase out. The initially slow pacing can also be a hurdle to viewers (I’d forgotten that I dropped this series initially after one episode). Shiki takes its time to build a solid world, but just about everything mentioned is used in some way to enhance the overall story. It may seem that I’ve gushed this entire review, but there are definitely flaws. The best thing about those flaws is that, in retrospect, they are far outweighed by all the elements which I think this series was attempting to use to pay homage to the source material that it seems inspired by.

Other fails include certain instances of CG in dream sequences; needless time jumps; in-scene time slowing, stopping, rewinding, and fast-forwarding; and an almost medical otaku approach to describing symptoms of those afflicted by the shiki. While the latter works in well by using the focus of a medical professional to approach Shiki’s premise in a real-world manner, its drawn-out instances using over-the-top medical jargon can easily make the audience phase out. The initially slow pacing can also be a hurdle to viewers (I’d forgotten that I dropped this series initially after one episode). Shiki takes its time to build a solid world, but just about everything mentioned is used in some way to enhance the overall story. It may seem that I’ve gushed this entire review, but there are definitely flaws. The best thing about those flaws is that, in retrospect, they are far outweighed by all the elements which I think this series was attempting to use to pay homage to the source material that it seems inspired by.

Footnote: page 148, The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms