Medium: Manga (3 volumes in Japan, 2 volumes in North America)

Medium: Manga (3 volumes in Japan, 2 volumes in North America)

Author: Osamu Tezuka

Genre: Adventure, Fantasy, Romance

Publisher: Kodansha (JP), Vertical, Inc. (US/CA)

Serialized in: Shoujo Club (JP)

Demographic: Shoujo

Release Date: Jan 1963 – Oct 1966 (JP), Nov 1, 2011 – Dec 6, 2011 (US/CA)

Age Rating: 6+

Vertical, Inc. has struck again with Princess Knight, a classic story by the “god of manga” Osamu Tezuka. The manga critics have all gone wild over it, praising the two-volume series for its examination of gender identity and its swashbuckling action. Frankly, though, I think Tezuka’s other masterpieces may have created a bit of over-hype for Princess Knight, as it is, in my opinion, one of the weaker manga in Tezuka’s English canon.

Frequently cited — somewhat inaccurately — as the series that sparked the entire shōjo (girls comic) style, Princess Knight is also particularly notable for being one of the many manga for girls but written by a man. At the time there were very few women in manga, so it was expected for men to write comics for girls. However, many of the female manga artists who came to prominence in the 1970s, known collectively as the Showa 24 Group, would later cite Princess Knight as one of the series that inspired them to make their own manga.

Sapphire, the protagonist of Princess Knight, is both hero and heroine, since the mischevious angel Tink accidentally gave her both a boy and a girl heart before she was born. Since she is the heir apparent to the kingdom of Silverland, Sapphire’s gender is quite important; women can’t inherit the throne! To prevent the nasty Duke Duralumin’s idiot son from becoming prince, her family raises Sapphire as both boy and girl, and she spends part of the day fencing and fighting, and another part picking flowers and talking to woodland creatures. God sends Tink down to Earth to fix his mistake and get back Sapphire’s boy heart.

Meanwhile, beneath the facade of her princely life, Sapphire longs to fully embrace her girl side, and even wears a blonde wig to a carnival, wherein she meets the dashing Prince Franz Charming. But things go awry when Charming and Sapphire engage in a tournament as princes, and the nasty Duke Duralumin poisons Charming’s sword in an attempt to kill Sapphire. A few hijinks later and the king is dead, Charming is accused of murder, and Sapphire’s identity is revealed. She loses not only the throne, but her freedom as well: she and her mother find themselves locked in jail by their own people. For the remainder of these two thick volumes, we follow Sapphire’s journey to regain the throne, win the love of Prince Charming, and escape the wiles of not only Duke Duralumin, but also Madame Hell, an appropriately named devil woman who wants to steal Sapphire’s girl heart and give it to her own daughter.

Some critics have celebrated Princess Knight for its subversion of traditional gender roles, but ironically this is precisely where the manga fails to connect. Perhaps by the most liberal definition of the term, Vertical could claim that this is Tezuka’s “proto-feminist” masterpiece (as they do on the back cover), but it hardly applies to a story in which Sapphire’s girl heart gives her the ability to pick flowers and her boy heart gives her the ability to swordfight. I fact, in many cases she loses one heart or the other, and Tezuka makes it very clear that without the boy heart, she loses all of her strength and will to fight. (Get ready for gripping lines like “Oh no, I feel weak all of a sudden. I feel like my boy heart’s been sucked right out of me! Oh, I’m so scared!”)

The second volume features a bit more criticism of traditional gender roles, portrayed with classic Tezuka bluntness via a group of women who lock themselves in a castle and fight off the men in order to protect Sapphire. The most striking moment of this scene is when Sapphire — equipped only with a sword and her girl heart — fights off a villain she could only defeat previously when she had both hearts. Here it seems that Tezuka is making a more direct correlation between her fighting ability and Sapphire herself (rather than her gender), but it’s such a long time coming and it comes from so far out of left field that it seems almost accidental.

The second volume features a bit more criticism of traditional gender roles, portrayed with classic Tezuka bluntness via a group of women who lock themselves in a castle and fight off the men in order to protect Sapphire. The most striking moment of this scene is when Sapphire — equipped only with a sword and her girl heart — fights off a villain she could only defeat previously when she had both hearts. Here it seems that Tezuka is making a more direct correlation between her fighting ability and Sapphire herself (rather than her gender), but it’s such a long time coming and it comes from so far out of left field that it seems almost accidental.

The gender commentary isn’t the only place where the presentation and pacing leave their marks, though. The entire manga runs at a breakneck pace, and major developments occur at such a striking speed that it can be difficult to keep up. Futhermore, when introducing characters, Tezuka wastes no time in explaining straight to your face exactly how they feel about everything, without the slightest hint of subtlety. For instance, within the first few pages of Sapphire meeting the pirate captain Blood, not only has he professed his instantaneous love for her, but she has introduced herself with the brilliant line “I promise I’m not a shady person.”

Despite a whirlwind of events surrounding her, watching the eponymous Princess Knight can be downright boring. She’s certainly not a passive Dinsey princess, but generally things happen to Sapphire, and she rarely does anything herself, making her little more than an object for the plot to bounce off of. Indeed, at one point near the climax she is bedridden, waiting for other characters to bring her the help she needs. Madame Hell’s daughter Hecate, a hip, rebellious young devil girl who opposes her mother’s plan to marry her off to Prince Charming, is a much more interesting heroine, and suffice it to say that a character named “Prince Charming” hardly ranks among Tezuka’s most layered protagonists.

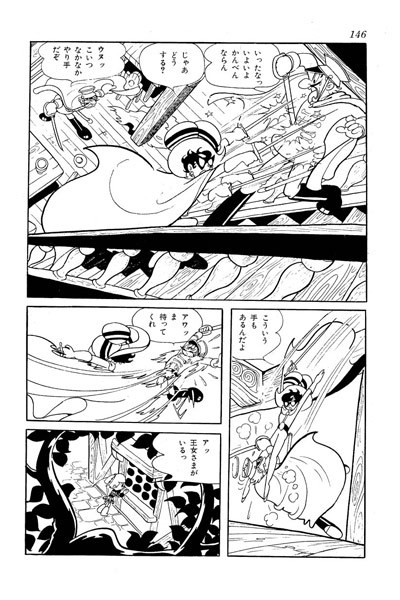

The comedy is the one aspect of Tezuka’s style that remains consistently on-point in Princess Knight. There are lots of one- or two-panel visual gags that punctuate the action just long enough to induce a chuckle before he gets back into the main story, and they have the same sort of non-sequiter, anachronistic charm that we’ve come to expect from the author. None of this is all that surprising, since in the early 1960s Tezuka was still largely writing for children, and was still known for his gag antics.

This, of course, extends equally to the art, which falls much closer to Astro Boy (1952) than later works like Ode to Kirihito (1966), which makes sense considering that Princess Knight‘s original run was concurrent with Astro Boy (Tezuka reworked the series for a 1963 rerelease, the version used for the Vertical edition). While its overall tone is reminiscent of Astro Boy, it achieves an appropriately fairy-tale aesthetic through the use of super-clean lines, simple, bubbly shapes, and generally lighter tones. Readers may also notice that, in addition to the overwhelming Disney influence on the designs of the characters and backgrounds, Tezuka also takes cues from early shojo adventure comics like Katsuji Matsumoto’s The Mysterious Clover (1934).

Princess Knight is, quite frankly, a baffling read. It seems to fly by even faster than Astro Boy, but unlike the richly established world and characters of that series, this feels more like a clumsy pastiche of Disney fantasy-adventure films. What’s more, the gender commentary is bluntly feminist at best and downright sexist at worst, and the entire work feels largely purposeless. It pains me to say this, but I can’t recommend Princess Knight unless, like me, you feel the need to plumb the depths of Osamu Tezuka’s English-language catalog. Perhaps in its time Princess Knight may have captivated its young audience, but today it serves as a reminder that even a god makes mistakes every once in a while.