Review: Mary and the Witch’s Flower

Ghibli Minus Ghibli

Since the early 1990s, the founders of Studio Ghibli have repeatedly failed to groom successors to their animation empire. Ocean Waves was intended to train up a new generation of creators, but it went over budget, seemingly prompting them to scrap the idea. Yoshifumi Kondo seemed a likely successor, but he died shortly after directing his first Ghibli film, Whisper of the Heart. More recently, studio president Toshio Suzuki tried to recruit Hayao Miyazaki’s son Goro, with disastrous results. By 2014 there were four active directors at Ghibli: Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, Goro Miyazaki, and Hiromasa Yonebayashi, the youngest person to ever direct a film for the studio. Yonebayashi’s two films, The Secret World of Arrietty and When Marnie Was There, are relatively quiet affairs. Both have an understated charm that made them critical successes but financial disappointments for a studio accustomed to Miyazaki blockbusters. He may not be the true successor to Miyazaki and Takahata, but when Ghibli went into hibernation in 2014, Yonebayashi carried on its legacy in the form of Mary and the Witch’s Flower (2017).

Mary is the first production from Studio Ponoc, founded by ex-Ghibli producer Yoshiaki Nishimura (The Tale of Princess Kaguya, When Marnie Was There). As it was produced in the period between Marnie and Miyazaki’s upcoming comeback film, Nishimura was able to recruit a number of ex-Ghibli staffers for the project, effectively making it a Ghibli production without the Ghibli infrastructure or management.

The similarities don’t stop at the staff credits. Like many Ghibli films, Mary is based on a Western novel. In this case, it’s The Little Broomstick by Mary Stewart. The title character just moved out to what appears to be the Scottish countryside, where she’s none too happy about her lack of friends and abundance of frizzy red hair. But when two cats lead her to a broomstick in the forest, she discovers a world of magic floating just above the clouds complete with a prestigious school for witchcraft and wizardry (no, not that one).

Compared to Yonebayashi’s previous outings, the movie is more in line with Miyazaki’s work with a spunky witch heroine, quirky mechanical designs, and a literal castle in the sky. But despite the surface similarities, Mary lacks something of Yonebayashi’s mentor’s ambition; the heroine’s arc is a bit simplistic, the magic isn’t particularly inventive, and the magic school is frustratingly unexplored. That said, this is hardly a bad movie. It’s brisk and satisfying, especially, I’d imagine, for children, who will eat up its cute animals, magical spells, and exciting chase sequences. There’s also a nice message about accepting yourself for who you are, but on-the-nose moralizing and a bit too much exposition saps it of the awe we tend to expect from Ghibli (or Ghibli-esque) movies.

A lot of what makes it feel so much like Ghibli is the character designs. Designer Akihiko Yamashita, with credits on Howl’s Moving Castle, Arrietty, and Tales from Earthsea, is a veteran of modern Ghibli, and he doesn’t stray far from the house style here. Everything is drawn with the soft, almost liquefied shapes of post-Howl’s Miyazaki, and the acting has a satisfying springiness to it. Clearly very little was lost production-wise in the migration to Ponoc.

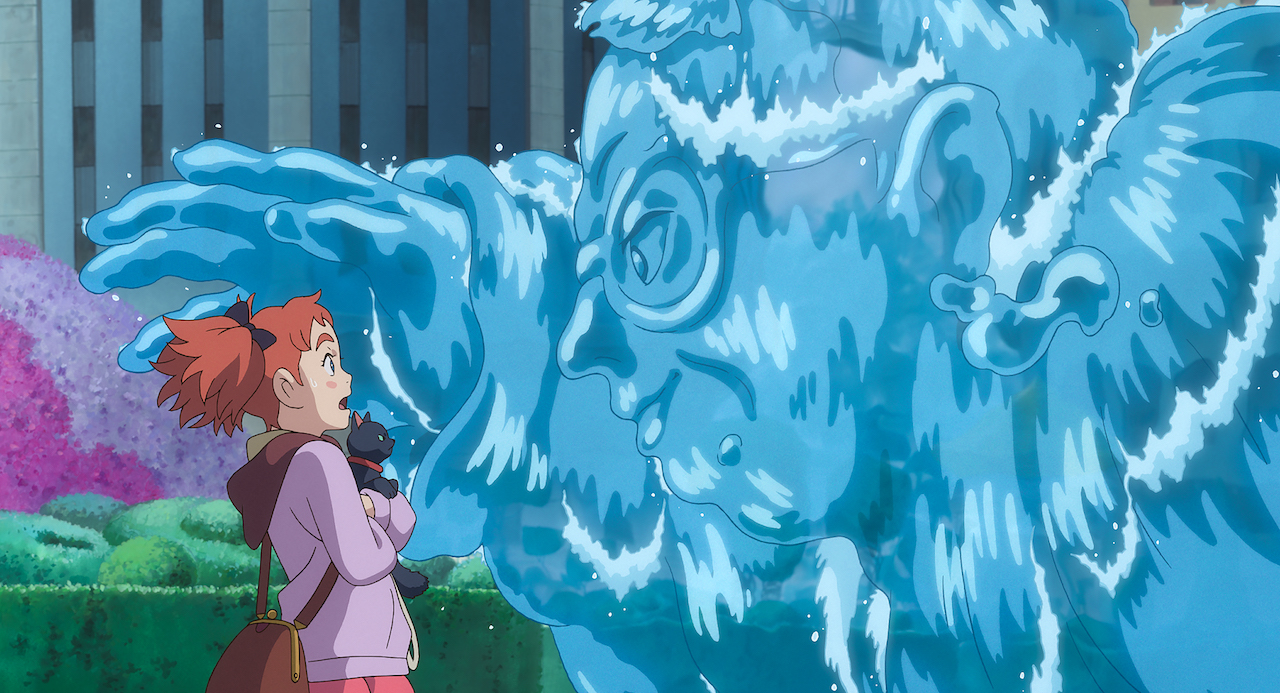

Mary also heavily relies on a motif of magical fluids and slimes, including a memorable early sequence that introduces the headmaster of the school. It’s a little disappointing that there isn’t a greater variety of magic on display, but the animation team sure delivers. The kings of wobbly, undulating motions, Shinya Ohira and Shinji Hashimoto, appear to have animated a number of shots, many of which stand out for their sharpness against a backdrop of softer motions. There’s a hint there of something new and not particularly Ghibli-esque — at the old studio, animators’ work would often be smoothed out to fit Miyazaki’s style. Yonebayashi may be more forgiving of their idiosyncrasies. He also clearly has a greater appetite for digital animation, as many scenes appear to make heavy use of post-processing effects.

While much of the film takes place in the school, the scenes on the ground are lovingly rendered. They capture the pastoral environment so well that I found myself wishing the film spent more time there. Art director Tomotaka Kubo previously worked for expressionist Shichiro Kobayashi (Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro), but he opts for softer, naturalistic backgrounds here. The color design and backgrounds sometimes lack the cohesion and attention to detail that was often present in Ghibli’s work, especially in the fantasy scenes, but Mary only suffers by way of comparison. By all accounts, this is a beautifully designed film.

GKIDS’ English dub commits to the location by giving everybody appropriately Scottish accents (at least to my untrained American ear). Ruby Barnhill is wide-eyed and reckless as Mary, while Kate Winslet and Jim Broadbent remain listenable in fairly goofy roles as the heads of the school.

Hiromasa Yonebayashi may departed from the Ghibli empire, but he clearly hasn’t left it all behind. Mary and the Witch’s Flower is “Ghibli Minus Ghibli” — the closest approximation of the studio’s style I’ve ever seen. It’s an admirable attempt, but it’s also a little disappointing. The dream of passing on the Ghibli legacy to a new director is dead. The closest thing we have to a “next Miyazaki” is Makoto Shinkai, who learned to be a filmmaker all on his own. But Shinkai will never be Miyazaki, and neither will Yonebayashi. Mary and the Witch’s Flower is a wonderful monument to Ghibli, but hopefully it represents a closing of that chapter of Yonebayashi’s career and the beginning of a new one that is informed by and not beholden to his legendary mentor.