Review: Lost Memories Dot Net

A short, sweet time capsule of online fandom

Before this here blog, Ani-Gamers, existed in its current form, it was an anime fansite called Anime Paradise, my ambitious follow-up to, *ahem*, “Vampt Vo’s DBZ” (yep, a Dragon Ball fansite). It was 2003, I was 12 years old, and the Web was new(-ish), a vast wonderland of haphazardly designed sites offering information about my favorite anime as well as ones I’d never even heard of. Dragon Ball GT! Azumanga Daioh! This cool new pirate thing called One Piece! But most importantly, it offered a chance to connect with other people who were into the same weird stuff as me, whether they were one town over or a continent away. Lost Memories Dot Net, a free game from indie designers Nina Freeman and Adam Freedman, is a time capsule of that particular moment on the Web, when many people my age were first forming our online identities and discovering anime fandom. That and falling in love.

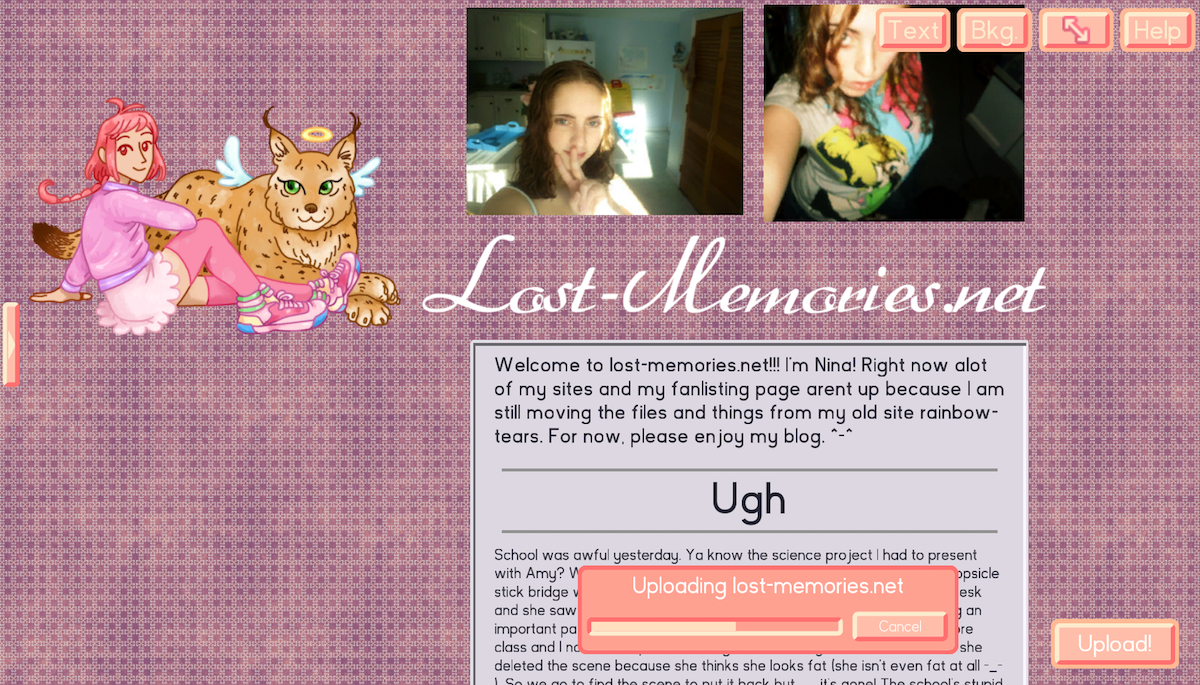

Like many of Freeman’s games, Lost Memories is semi-autobiographical. You play as Nina, a middle-school girl who runs a blog called lost-memories.net that is focused on anime, video games, and her daily escapades at school. The entire game, played within a simulated web browser (inspired in part by extensive Wayback Machine research), offers the ability to navigate to other sites, download images, and design your own home page. These elements provide a fascinating backdrop, but the story itself lives in an instant messaging tab. There Nina can chat with her buddies, who include a distant online friend as well as her best friend and a childhood friend who she’s got a crush on. Naturally, the three find themselves in a love triangle. You guide conversations through limited dialogue choices and seemingly have at least a slight effect on the final outcome.

The mechanics of Lost Memories are extremely simple, but it’s more about using interactive elements to immerse you in a particular state of mind than it is about overcoming specific challenges. It wouldn’t be unfair to describe it as a visual novel, especially since there is often only one dialogue “choice” in a conversation, making it more like a traditional book than a choose-your-own adventure. Still, there’s something to be said for letting a linear narrative play out in an interactive hypertext browser, where the user is free to pause the conversation and interact with other pieces of multimedia before coming back and continuing the story. When a character would mention another blog, I would often click the link and end up reading through the posts on the site, an interruption to the narrative flow that is a unique feature of the Web and our modern information society.

The website design mechanic is fairly robust by contrast. You can download images from friends and other sites and then place them onto the page at any position, size, and orientation you want. (Unfortunately, positioning things on real websites in 2003 was not such a walk in the park.) As you progress, you end up with more and more avatars, drawings, and backgrounds, which enables a greater range of designs in turn. Your choices in this mode don’t seem to have any effect on the story, but the mini-game is an enjoyable enough diversion and opportunity for creativity that, again, serves to break up the linear narrative.

Love triangles aren’t really my bag, and the chat-based narrative doesn’t take many particularly unexpected turns, but for me what is most captivating about the game is its atmosphere. Everything from the asynchronous chat mechanic to the small web of simulated anime and video game blogs to the embedded music player serves to resurrect a time and a virtual place that seems quaint and idyllic compared to the corporatized, hyper-political Web of 2017 (though there’s at least one instance of online harrassment that feels particularly true-to-life). Nina doesn’t just play out a real-life romantic and family drama over IM. She relays it to a far-off friend, whom she’s never met, pouring her soul out before sending over roughly Photoshopped images of their favorite anime characters. It’s a kind of anonymous multimedia therapy unheard of in the pre-Internet era.

For those of us who have become a bit jaded about the potential for this international network to forge genuine human connections, there’s something energizing about seeing things through younger, more innocent eyes. I’m most curious, however, about the effect Lost Memories might have on people outside of my generation who didn’t experience its subject firsthand. Will they see it as an aspirational goal? Or a doomed utopia? As someone who works on the Web both as a writer and developer and still envisions the digital commons as a powerful, liberating force, I hold out hope for the former.