Review: Joshi Kausei

Show (a little too much), Don't Tell

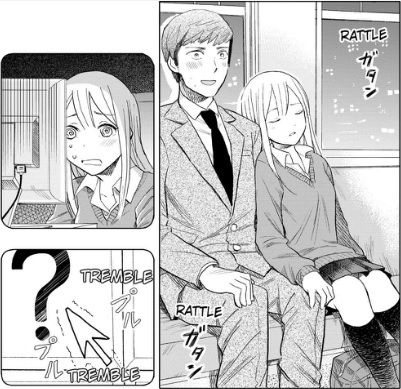

Ken Wakai’s manga Joshi Kausei (JyoshiKausei), which should not be confused with Towa Oshima’s Joshi Kousei (High School Girls), is an exercise in show, don’t tell—the art of relaying a story without relying upon dialog to spell things out for the reader. Joshi Kausei focuses on random moments in the fictional life of Momoko, “a high school girl who’s super laid back.” Although the situations—wandering around, cooling off on a hot day, riding home on the train, etc.—are often quite simple, there’s a good deal of ingenuity and heart behind their conveyance. There’s also some cheating regarding the whole dialog-free concept and, unfortunately, more than some voyeurism issues, but overall this is a lighthearted and unexpectedly enjoyable portrayal of “The leisurely life of a carefree high school girl” (and, vis-à-vis, youth in general).

The short, slice-of-life skits comprising each chapter carry more of a reflective air than an observational one, meaning that reading along feels more like remembering than discovering. This works exceptionally well for highlighting the same sort of trivial things most people do but take for granted as youths—carrying around random objects and finding the myriad uses for which they were not originally intended,  the odd moments that make up the majority of the time spent hanging out with friends in private and in public, the circumstances behind how certain friends came to be friends—and imbuing the depictions of which with a very realistic human warmth. As natural as the stories feel, however, the manga is at its best when playing with juxtaposition and transposition. Whether it’s by twisting the trite, playing on tropes, or using the pacing and sequencing of specific events to reap a legitimate surprise, the manga has a very real talent for eliciting chortles and “ha!”s.

the odd moments that make up the majority of the time spent hanging out with friends in private and in public, the circumstances behind how certain friends came to be friends—and imbuing the depictions of which with a very realistic human warmth. As natural as the stories feel, however, the manga is at its best when playing with juxtaposition and transposition. Whether it’s by twisting the trite, playing on tropes, or using the pacing and sequencing of specific events to reap a legitimate surprise, the manga has a very real talent for eliciting chortles and “ha!”s.

On the flip side, Joshi Kausei is at its creepiest when lurking like a stalker armed with a cellphone camera. Take Chapter 2 or Chapter 18, both of which are dedicated to the stripping off of clothes, for example. There are also several changing scenes, arguably incidental lewd poses, and unfortunate angles aplenty that seem drawn to titillate a voyeuristic audience. For almost every questionable shot, there seems to have been a better way it could have been drawn. But the fan service is not always leveraged for lasciviousness. In fact, all of the above might not be intended as fan service at all. In addition to a couple of moments wherein they are used as bait-and-switch humor, catalysts for the refreshingly unexpected, or for depiction of strain (see dentist chair Chapter 17), the multitudinous panty shots and poses can be viewed as portrayal of a youth not mindful of the world around her and totally fascinated by the world before her. Of course, who the reader is plays a large part in how the content is interpreted, but as this is a seinen manga, I’ll leave judgment up to any and all of the individuals who flip through the digital pages.

On the flip side, Joshi Kausei is at its creepiest when lurking like a stalker armed with a cellphone camera. Take Chapter 2 or Chapter 18, both of which are dedicated to the stripping off of clothes, for example. There are also several changing scenes, arguably incidental lewd poses, and unfortunate angles aplenty that seem drawn to titillate a voyeuristic audience. For almost every questionable shot, there seems to have been a better way it could have been drawn. But the fan service is not always leveraged for lasciviousness. In fact, all of the above might not be intended as fan service at all. In addition to a couple of moments wherein they are used as bait-and-switch humor, catalysts for the refreshingly unexpected, or for depiction of strain (see dentist chair Chapter 17), the multitudinous panty shots and poses can be viewed as portrayal of a youth not mindful of the world around her and totally fascinated by the world before her. Of course, who the reader is plays a large part in how the content is interpreted, but as this is a seinen manga, I’ll leave judgment up to any and all of the individuals who flip through the digital pages.

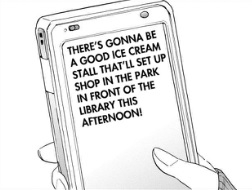

Even if one chapter seems offensive, there’s most likely an inoffensive chapter that follows shortly, if not immediately, thereafter. While the longest chapter comes in at around 20 pages and the shortest is around 10, most fall in-between at around 15 or 16. This is a perfectly ample amount of space with which to tell the intended short stories, which are, true to Wakai’s mission statement, free of dialog. There’s some mild cheating here and there though, and some of it is a clever way to skirt the guideline. A teacher’s dramatic hand slap against a blackboard message: clever. A lengthy cellphone text pointing out unnecessary details: unfortunate. Sound effects EVERYWHERE despite an adeptness at indicating motion in still images: gratuitous at best. An adjective floating above a character’s head while she’s already drawn tellingly: unforgivable. Luckily, all of those instances (save the sound effects) are pretty rare.

Even if one chapter seems offensive, there’s most likely an inoffensive chapter that follows shortly, if not immediately, thereafter. While the longest chapter comes in at around 20 pages and the shortest is around 10, most fall in-between at around 15 or 16. This is a perfectly ample amount of space with which to tell the intended short stories, which are, true to Wakai’s mission statement, free of dialog. There’s some mild cheating here and there though, and some of it is a clever way to skirt the guideline. A teacher’s dramatic hand slap against a blackboard message: clever. A lengthy cellphone text pointing out unnecessary details: unfortunate. Sound effects EVERYWHERE despite an adeptness at indicating motion in still images: gratuitous at best. An adjective floating above a character’s head while she’s already drawn tellingly: unforgivable. Luckily, all of those instances (save the sound effects) are pretty rare.

If you like cute girls doing cute things, this manga’s right up your alley. Despite its unfortunate (read: creepy) aspects, it manages to be cute and warm and, in some instances, quite witty. The amount of universally identifiable material makes me wonder if I actually grew up as an adolescent girl, which also makes me wonder why Wakai, who handled both the “writing” and illustrations, is drawing girls instead of guys. Though, with all the gaze pandering (be it for audience or self), I guess that’s sadly not too tough to assume. Futabasha originally published Joshi Kausei, which Google Chrome humorously translates as “Woman Cow Students” on Wakai’s blog, where he tells a little about his thoughts on each chapter. If you’d like to read/see more of Wakai’s work, he also contributed to the Daily Lives of High School Boys anthology and, perhaps more tellingly of his tendencies, authored one more title.