He Fucked The Girl Out Of Me is one of those rare works that is at once deeply personal, whilst also being universal, familiar, and even mundane. The narrative is painfully and uncomfortably close to life as it is experienced every day through the eyes of its protagonist, Ann, as told by solo developer Taylor McCue. Ann’s traumatizing steps into sex work serve as a desperate salve to the pain of being transgender, poor, and ill. Although largely autobiographical, the work is a composite of memories: details are changed and shifted, and the story covers a loose and shifting time period to examine events that happen achronologically.

The game is presented in an achingly gorgeous but simple pixel art style, with only two or three colors in every screen. It feels like the memory of your favourite Game Boy game, or the first time you were enticed by a screenshot of Yume Nikki on the internet and thought “what the fuck is that”. The visuals are constantly shifting; now highly abstracted moodscapes, now a painfully real place brought to life in the pixel aesthetic. Even the protagonist Ann swirls and shifts from scene to scene, the reality of her physical form changing as the narrative jumps around and reaches a climax. The level of abstraction makes it feel much more personal than the endless hours of perfectly mo-capped cutscenes that every game these days must have. The game unrelentingly pushes you through its scenes, allowing you only to walk around and move the dialogue forward with a single button. You try to explore the map, looking for secrets, ways out: there is nothing but a static, unmoving forward path that locks you into the inevitable conclusion. I was compelled to replay it over and over to see what I had control over. The answer was precious little.

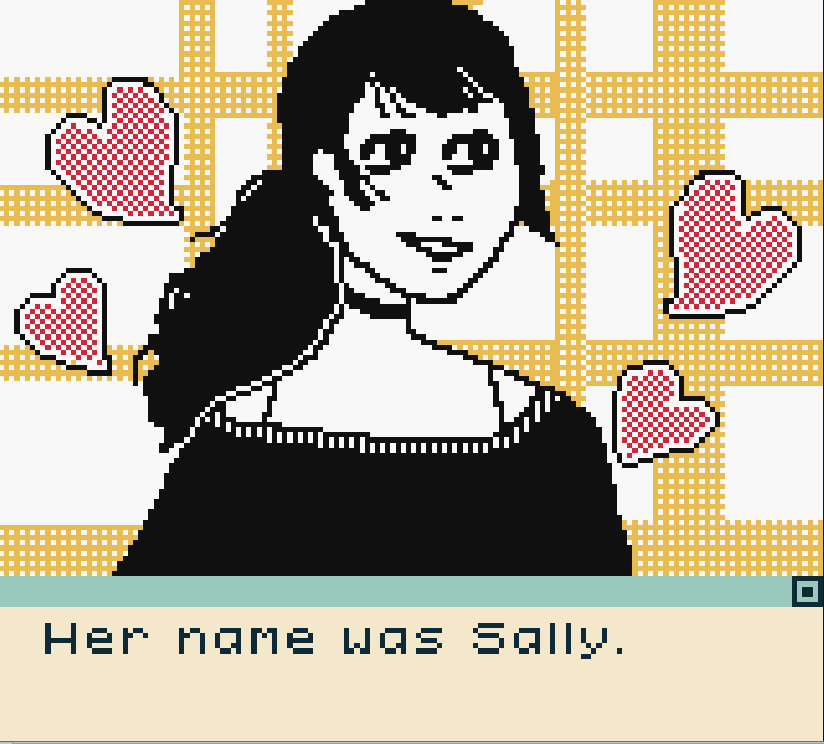

I’d hate to spoil too much of the story, but as you might imagine from the title, Ann is drawn into sex work as a result of the high cost she pays for being alive. Sex permeates HFTGOOM, largely not as a human longing or an abstract pleasure, and definitely not as something to be enthusiastically negotiated and consented to. Ann’s friend, Sally, convinces her sex work is safe and undemanding. Fun, even. Ann looks up to Sally, and loves her; trusts that Sally is a person with her best interests at heart. But the experience for Ann is demoralizing. You witness a carefully crafted sense of self disappear in an experience that feels akin to sexual assault. The John feels strongly that he deserves punishment for his urge to crossdress, and looks to sex work neophyte Ann to do the punishing. The slippery, shifting boundaries of gender can be both very affirming, and deeply upsetting and confining. And we see this throughout the course of the game: the fetishized nature of transgender existence, through repeated references to paraphilia and sex acts that become overwhelming. There’s no simple adult transaction, no “hello my name is John, I was looking to do incall Wednesday or Thursday evening for two hours?” In the middle of being traumatized for life, Ann even admits to feeling bored, stressed, uncomfortable, wanting the experience to just be over like it’s an experiment you got bored with and won’t try again.

Transgender people occupy a difficult place in 2023, constantly vilified by the worst people in our society and yet fetishized, desired for the same reason people like Ann fear starvation, ostracization, or even death. This conflict plays out through the course of the game’s story as the trauma of it haunts the protagonist. HFTGOOM convincingly paints the transgender experience as one of being viewed as inherently sexual, having sexuality shoved onto you regardless of your own qualities. As a cis person it’s a thing I’ve had to experience through media specifically about the transgender experience. But it’s impossible to dictate how someone will react to any given work, as HFTGOOM painfully and abruptly demonstrates in its opening seconds. Once I lent a friend of mine the novel Little Fish by Casey Plett once, a book I found incredibly affirming and hopeful: a story about working retail in Winnipeg and working a shitty retail job, where life despite its bitterness was worth living. But my friend’s reaction to the book was to call it harrowing. To her it was a Dickensian portrayal of poverty and suffering. It frustrated me that she could only see the bitterness, the unpleasantness, and not the strong desire to live even if it meant sometimes life just sucked.

HFTGOOM is also largely about trying to live with trauma. Notably, the many things haunting the story don’t end or resolve: they just are. It captures — perhaps more powerfully than any other work I’ve experienced — how it feels to break, and then see the world around you unbroken. There’s a one-off sequence where the one sound effect in the whole thing heralds an uncomfortable conversation with the protagonist’s parents, and an achingly painful deadnaming. In exploring trauma the achronological, semi-fictional nature of the narrative works in its favor. It’s not a set, correct presentation of events that happened: it’s forks of possibilities, shards of time and place that blend together and shatter again, swirling around to compose the mind of a single individual. Ann feels forced to live her life in that moment: “I find myself comparing every economic choice to what happened to me,” and sees everything become transactional. In another part, Sally pushes Ann to take too many samples off of food service workers at the food court to train her to be a sex worker. In Sally’s words, people are too nice, giving up more than you would think before saying no. It’s a blatantly unfair assessment of power relationships that sums up almost every interaction in the game. And like what Ann goes through in the course of HFTGOOM, trauma can unstick you in time, living and reliving moments years or decades after they passed like Billy Pilgrim.

Making your way through HFTGOOM gives the player a sense of the danger of sex work. Not that sex work is bad (HFTGOOM explicitly says at its outset it is not meant to demonize sex work), but that the morals and structures of our society make it unsafe. The criminalization that keeps workers from practicing safely; the unethical and immoral basis of a society determined to punish sexual expression; and the desperate need for money and stability that forces people into it involuntarily. Something that’s left unsaid in the game is that the ruling class firmly believes only they should have access to medicine, shelter, justice and above all, self-expression, and people like Ann deserve to suffer.

I am not marginalized. I am cisgender, straight and white, so I can’t say I’ve experienced the unique circumstances Taylor McCue chose to portray in HFTGOOM. But I do have my share of trauma. I’ve known deep pain and suffering, hunger, desperate want, and expect to do so again before my time on this planet is finished. But the things that I’ve been through and the trauma that’s with me every waking second hasn’t made me, or (if I may be so bold) Ann, or Taylor McCue stronger. In my case it’s made me worse, more brittle, a lesser version of the person I want to be. And in playing HFTGOOM I kind of fell in love with Sally, too. She seems wonderful: worldly but uncynical, fun but not destructive, living for the moment in a way I aspire to but can’t seem to live out.

If it’s not clear at this point I can’t recommend this game enough. It deserves the superlative “vital”: if you’re the kind of person who plays half a dozen new games on some kind of subscription service every month, please make time for a unique experience like this one. It is the archetypical indie game, the argument for why the medium is relevant and alive with possibility. This is not the most flattering admission but I have difficulty working through my emotions. Playing HFTGOOM gave me the space I needed just to feel, to be vulnerable and hurt even if Ann and I haven’t been through the same things. Thank you, Taylor.