Review: Fireworks

SHAFT’s most accessible “mainstream” work yet

Fireworks, or the more verbosely titled Fireworks, Should We See It from the Side or the Bottom?, is a Studio SHAFT produced remake/animated adaptation of a 1993 Shunji Iwai film that began life as an individual episode of a television drama before receiving a theatrical release two years later in 1995. There’s a lot going on here, but to put it more simply: Fireworks is a romance story, refreshed for a modern audience, that is set in an idyllic summer and centers around teenagers interested in neither love nor fireworks … or so it would seem.

Featuring two young screen actors as the principle voices and the ubiquitous Mamoru Miyano as the third vertex in the love triangle, Fireworks is a lean and breezy 90-minute trip into the classic Japanese TV drama conventions of festivals, summer school, and time travel. While placing the leads of Kamen Rider W and the live-action Chihayafuru films together may do very little for foreign audiences, especially when divorcing their voices from their likeness, it nevertheless feels like a pivotal production decision that occasionally gives the film some more “oomph” during crucial moments. At the very least, doing this gives the audience something extra instead of serviceable, perfunctory anime voice acting. Cynically, I’m led to believe this is more of a stunt to drum up easy publicity, but the actors are clearly comfortable with the material and do a fine job throughout.

Fireworks is anime, but it feels as if it would like to be something more. From my admittedly limited knowledge of Shunji Iwai’s filmography, Hitoshi Ohne’s screenplay often makes me recall much of Iwai’s own writing, whether it’s characters talking big circles around seemingly minor (but often major) issues or even smaller touches like friends messing around and getting on each other’s nerves. Honestly, the “Japanese TV drama” script is more of a sideways leap from “late night TV anime” and Fireworks’ identity gets further muddled by the hands involved in the direction. Akiyuki Shinbo is credited as general director, with Nobuyuki Takeuchi credited as co-director, meaning this is through and through a SHAFT joint. Prepare for odd angles, back-to-back close-ups of inanimate objects and architectural wonders, and a dreamy sequence set to a Seiko Matsuda cover.

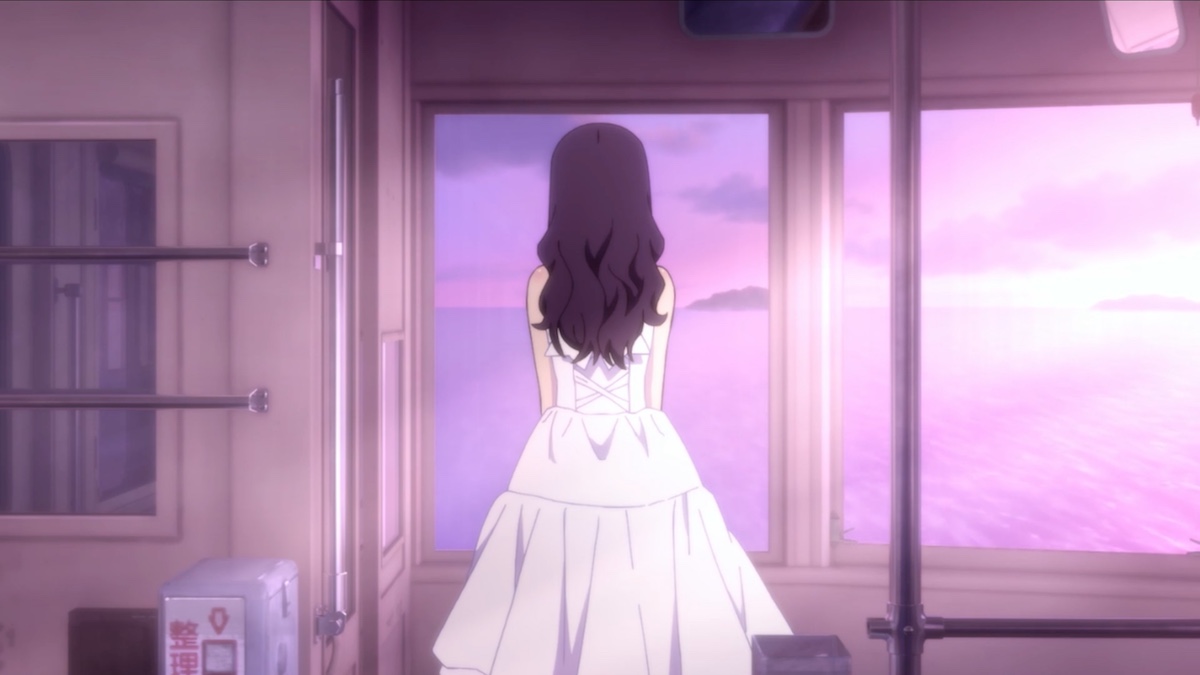

The film is as polished and attractive as its cast. Character designs were handled by Akio Watanabe, who could not help but craft, to the point of distraction, a very Senjougahara-esque heroine. Admittedly, Fireworks’ Nazuna is distant with her classmates and quietly deals with an unhappy home situation, so the comparison is a fair one, but it often feels like evocations of other work is a running thread in Fireworks (whether it’s on purpose or not). Being acutely aware of every cut of animation in the Monogatari Series means being unable to take Nazuna as a unique character instead of a branch of Watanabe’s general body of work, especially when comparisons are drawn to a character as iconic as Senjougahara. Nazuna will sing, fall off of a tall structure, and strip to her underwear before the end and never once deviate from the path set by Nisioisin’s tsundere stapler fanatic. What’s unfair to Nazuna is that she’s only given the frame of an hour and a half to establish her own identity and that, more often than not, her moments of characterization come off as SHAFT and Watanabe retreading old material that worked once before. Of course, this all amounts to nothing if one hasn’t seen Bakemonogatari, and the unfortunate truth of the matter is that this might be the point all along.

As far as SHAFT works go, this is likely their most accessible “mainstream” work yet … if we ignore the fact that SHAFT has been fairly mainstream for a while now. Still, Fireworks stands out to me in how conservative a work it is for a studio that only last year completed its ambitious Kizumonogatari trilogy — a set of films which took everyone’s ideas of “old SHAFT vs. new SHAFT” and smashed them to bits. This is a “safe” film, one you can show your parents or anime-adverse significant other. Fireworks is wholly sincere about the immortality of summer, adolescence, love, and every combination of the aforementioned terms. The film ends on a strong note, but there’s not much left to chew on when the product has been made so easy to swallow.

For all the star power attached to the project, I would expect more, but ultimately it’s not a film for animation nerds (lovely work here occasionally, though) or the passionate collective of SHAFT scholars. If we’re talking in lofty terms of “ambition” and “pushing the medium,” it’s none of these but should also not be dismissed as a flighty work-for-hire to keep the lights on. Fireworks is a middle-of-the-road film for a middle-of-the-road audience without an encyclopedic knowledge of the talent behind the work.

My own fondness of SHAFT aside, the irony is that my enjoyment of Fireworks is deeply affected by my appreciation of the Monogatari Series and that I can’t help but to come away from it with mixed feelings. The audience is much better served approaching it without familiarity with that monumental work (now approaching 10 years since its first television broadcast). I have personally spent a significant amount of time in my life attempting to convey why the Monogatari Series is such a critical work, but today it is a tedious conversation no one wants to hear from me. Finally, there’s a SHAFT film that packages all that I superficially like about Bakemonogatari for the your name. crowd. Still, perhaps, maybe you’re better off watching Bakemonogatari?