Review: Domu – A Child's Dream

Otomo's Psychic Showdown

Domu: A Child’s Dream is a single volume manga whose original run in Young Magazine finished only months before the beginning of its author (Katsuhiro Otomo)’s more famous contribution to the same magazine: Akira. It’s a very interesting read that uses many of the themes and visual stylings that would be dramatically expanded upon in Akira. On its own, Domu is a highly enjoyable speculative romp focusing on dark atmosphere and action sequences of cinematic execution.

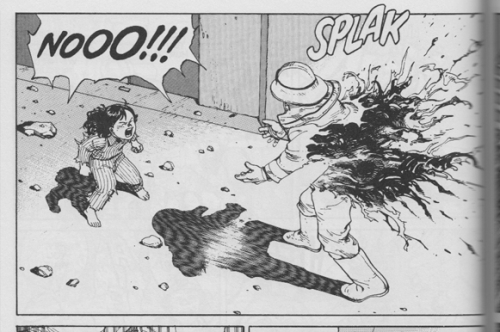

In what is assumed to be contemporary Tokyo, the Tsutsumi Housing Complex has experienced a series of unexplained deaths over the last three years. Responsible for the string of death is an old man, called “Old Cho” by his neighbors, with a child-like mind and strong extrasensory powers. His motives are that of a child — he sees something he wants, and takes it at the expense of the life of the owner. This may seem a spoiler, but despite the mystery tone of the narrative’s first half, it is clear to the audience who is responsible very early on. The first half deals with the investigation of one of Old Cho’s recent victims, switching between different members of the team encountering befuddling clues and strange events. Tensions deepen as a policeman and the head detective become the next victims. Simultaneously, another story unfolds as a young girl, Etsuko, who also has unexplained powers, becomes aware of the old man’s actions. The situation escalates as “Old Cho” reacts defensively to the threat of another being with similar powers. Midway, the story shifts from the slower paced mystery to a frenetic sequence of events, leading to a violent telepathic showdown between Cho and Etsuko.

The investigation angle is played throughout, but ultimately adds little to the narrative. It is intended as a way to explore the mystery of the unexplained deaths, helping the audience piece together facts over time, but it would have been more effective if the audience weren’t already aware of the culprit’s identity. Furthermore, the activities that prompt the climactic confrontation and eventual resolution are entirely independent of the investigators. Etsuko recognizes Old Cho’s powers without any prompting from the investigation, as she just happens to notice his silent manipulations while playing in the park one day. It would have been more sensible to focus on developing Etsuko and exploring the mind of Cho, downplaying the investigative element.

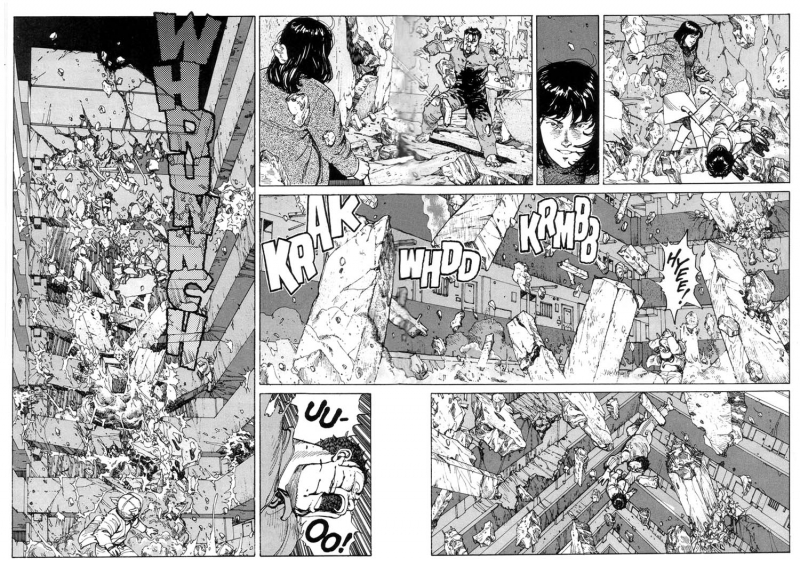

As for Etsuko, the audience never really gets to learn much about her, making her more plot device than person. Where the graphic novel truly succeeds, however, is in the latter half, the battle between Cho and Etsuko. The pacing rapidly accelerates, and becomes an unrelenting feast of manga action as the two wreak havoc in their attempt to destroy the other. This confrontation is one of the better action sequences in manga, without any of the messy linework or problematic pacing that often hurt the flow of such scenes. The final pages are absolutely brilliant with an eerily low-key finale that highlights the theme of the mysterious mind of children.

This hyper, telekinetic thriller defines Domu, and leaves little room for anything else — Otomo’s tale doesn’t use the story as a platform to tackle issues with any significant depth. That said, he does utilize some interesting concepts throughout, but as setting and not commentary. For example, link between a child’s mind and psychic powers is the central theme of the story, but Otomo didn’t really explore this until his work in Akira. Still, setting is an important facet of a story, and used effectively in Domu to develop the atmosphere of his work. Inspired by Otomo’s own experience moving to Tokyo, the apartment complex in Domu evokes the feelings of congested urban life. In an interview with Yomiura, Otomo commented on the people living in a recently developed public housing complex, saying that they “never seemed to adapt to this sort of crowd urban living, but they found themselves trapped in that world.” That feeling comes across very well in Domu, and serves as an effective backdrop for the story.

Domu is very much in the tradition of science fiction short stories, such as those found in “zines” like Amazing Stories and Analogue Science Fiction. This style of SF generally de-emphasizes characterization in order to focus on ideas. In the case of Domu, this is the battle between two extrasensory “children.” My attraction to Domu most likely comes from to my fondness for this mode of classic science fiction. Otomo weaves a clever narrative comprised of Old Cho, the subtle noir-esque atmosphere surrounding the apartment complex, and the captivating energy of the explosively violent climax. One strength of the lack of relatable characters is that there isn’t really much impact when they are killed; this may sound like a bad thing, but I appreciate that I can enjoy the story for what it is without being weighed down by emotionally manipulative drama. My only significant complaint is that I wish the investigative aspect were better weaved into the overall narrative.

As expected of Otomo, the artwork is incredible. The character designs stand out against manga’s tendency toward over-the-top designs; Otomo’s story is populated by everyday Tokyo residents who are appropriately plain, but readily distinguishable from each other. I find it amusing that, simply by resembling ordinary people Otomo’s designs seem out of the ordinary in manga. Outside of character design, the visuals are extremely capable at presenting the feel of the story. During the slower-paced beginning, the level of detail is adequate and realistic in a way that doesn’t really push the reader forward or force the reader to slow down and carefully examine the scenery. Many of the more dramatic scenes take place at night, when Otomo utilizes high black and white contrast to maintain a consistently foreboding atmosphere. Many panels in these night scenes feature well-formed lit apartments that create geometric visual interest and highlight the urban claustrophobia. As the pacing increases during the battle, the artwork elevates to a cinematic feel with further gorgeous night scenes and thought-out aesthetic composition that adds a certain stark beauty to the rampant urban destruction.

The entirety of the manga is highly readable, with a level of visual clarity that allows the reader to easily follow the story without ever getting dragged down. Panels instantly fixate the reader’s eye on the key detail, and even the scenes of destruction are structured in a way that the reader doesn’t get lost in speed lines and rubble. Otomo often uses sharp contrast and minimal shapes to create panels that are instantly comprehensible for an energetic reading of the plot, but are designed with enough artistic merit to reward a slower re-reading. According to Frederick L. Schodt in his classic text Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics, manga is a medium meant to be digested quickly. While there are many titles that seem to disagree with this assertion, if this is accepted as an ideal for the medium, then Domu is a demonstration of Otomo’s mastery of the “language” of manga — balancing clear readability with high-quality aesthetic design.

Dark Horse’s 2001 release is long out of print, but you can find an inexpensive copy online. Ebay currently has copies up for the startling prices of upwards of $45 and one Amazon listing shows even higher. However, I discovered that Domu is listed on Amazon twice, with the second featuring much better prices — as low as $1.65 for a copy described as “dirty” and another for $13.99 that claims to have been kept in a protective sleeve, “since day 1.” Domu is completely worth picking up for fans of Otomo and dark speculative fiction who enjoy works outside of hard sci-fi. Many anime fans demand high characterization to be a focal theme to enjoy a piece of writing, but Domu absolutely excels at what it is trying to be — a strong example of short story comic writing that is able to capture a compelling atmosphere and engaging action in a tremendously fun way.

Medium: Manga (1 volume)

Author: Katsuhiro Otomo

Genre: Science Fiction, Action, Mystery

Publisher: Kodansha (JP), Dark Horse (US)

Serialized in: Young Magazine (JP)

Demographic: Seinen

Release Date: 1982 (JP), 1995 (US)

Age Rating: Not Rated (we’d say about 16+, though)