Review: Akagi

Parlor Tricks

The year is 1958. There’s a tense game of mahjong going on between some shady characters in the backroom of a rundown parlor, when in stumbles a 13-year-old on the run from the fuzz. Welcoming this distraction as divine providence, the loser at the table with his life (insurance) on the line offers the boy an alibi in exchange for swapping places at a do-or-die moment in the match. The gamble works – for the player, for the kid, for one of the cops, and for the audience.

The year is 1958. There’s a tense game of mahjong going on between some shady characters in the backroom of a rundown parlor, when in stumbles a 13-year-old on the run from the fuzz. Welcoming this distraction as divine providence, the loser at the table with his life (insurance) on the line offers the boy an alibi in exchange for swapping places at a do-or-die moment in the match. The gamble works – for the player, for the kid, for one of the cops, and for the audience.

Akagi is about a kid named (wait for it) Akagi, who is one part adrenaline junkie and other part psychological mastermind. He’s never played a game of mahjong in his life (which makes two of us) but is quick to learn and even quicker to leverage opponents’ vulnerabilities for the win. The anime, with an appropriate alternative title of Mahjong Legend Akagi: The Genius Who Descended Into the Darkness, consists of three arcs that take viewers through the defining points of the legacy—from initial rise to infernal fame—as wrought in the seedy world of underground mahjong.

Going in, as alluded to above, I hadn’t the slightest clue as to the intricacies of mahjong—not the existence or names of the different rounds nor the types of winning hand combinations or tiles that comprise them—and I still don’t; mahjong, to me, is dominoes using funky tiles with engraved pictures and foreign writing. Though, to be completely honest, I put zero effort into attempting to learn the rules of the game from the show. With regards to enjoying the anime, however, this is of little consequence.

Going in, as alluded to above, I hadn’t the slightest clue as to the intricacies of mahjong—not the existence or names of the different rounds nor the types of winning hand combinations or tiles that comprise them—and I still don’t; mahjong, to me, is dominoes using funky tiles with engraved pictures and foreign writing. Though, to be completely honest, I put zero effort into attempting to learn the rules of the game from the show. With regards to enjoying the anime, however, this is of little consequence.

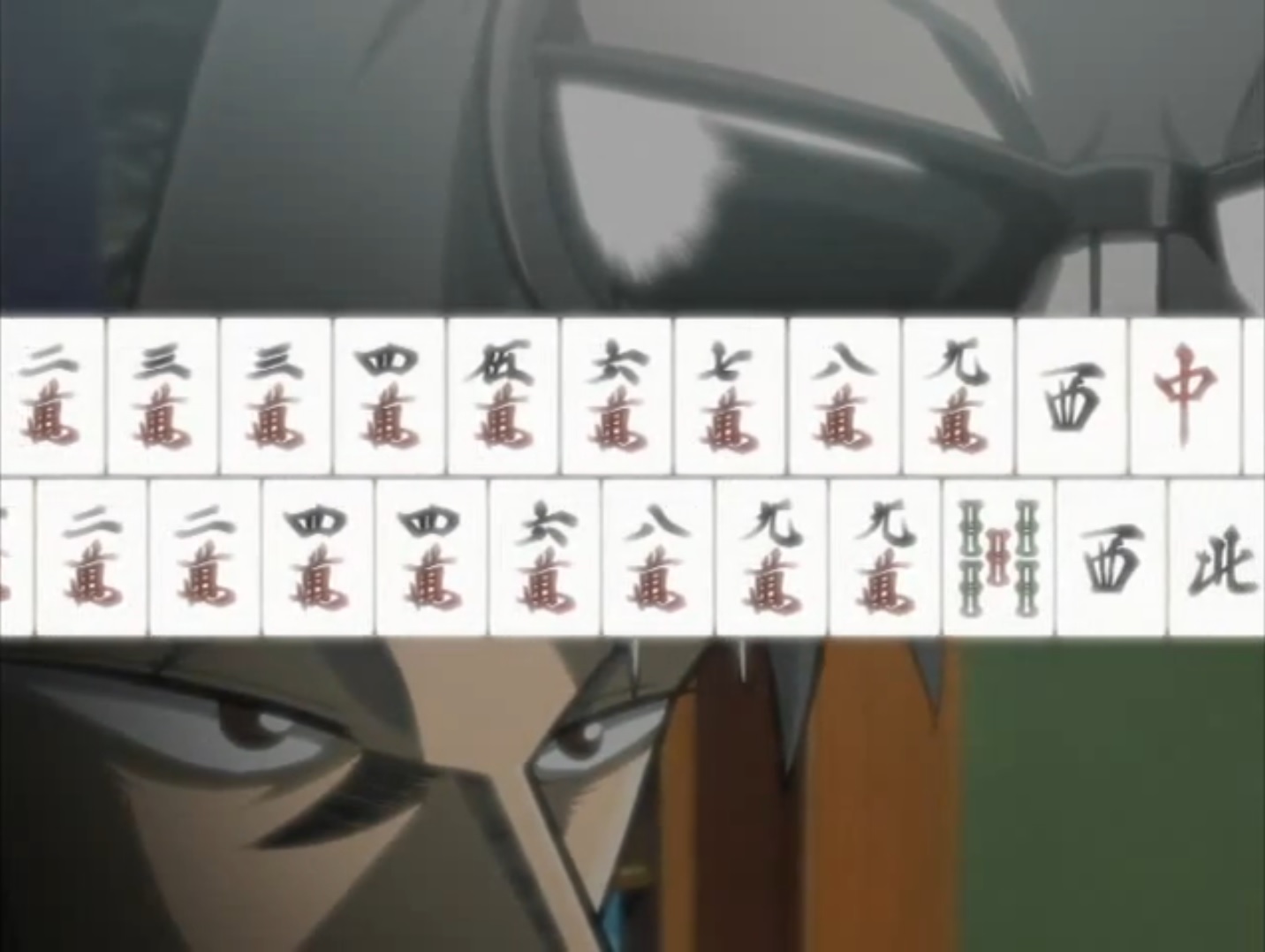

Voiceover narration baby-steps viewers through what I assume are mahjong fundamentals—favored tile groupings, in-game calls, winning hand names—in order to initiate the ignorant. I can only imagine this to be as irritating to mahjong players as redundant dialog explaining depicted emotion is to English majors, but at least the basics are only explained once. Repetition, by way of illustration and example instead of info dump, did begin to ingrain some gameplay basics into my dense noggin by the end of the series, which is appropriate seeing as the majority of the 26 episodes are spent mulling over strategy. At the end of each match, however, it is not the names of things that matter but rather the ways in which the decision making process is executed.

Voiceover narration baby-steps viewers through what I assume are mahjong fundamentals—favored tile groupings, in-game calls, winning hand names—in order to initiate the ignorant. I can only imagine this to be as irritating to mahjong players as redundant dialog explaining depicted emotion is to English majors, but at least the basics are only explained once. Repetition, by way of illustration and example instead of info dump, did begin to ingrain some gameplay basics into my dense noggin by the end of the series, which is appropriate seeing as the majority of the 26 episodes are spent mulling over strategy. At the end of each match, however, it is not the names of things that matter but rather the ways in which the decision making process is executed.

Were it not for the integrated yet juxtaposed efforts of the animation studios involved with Akagi, it would be easy to zone out during explanations of hands or the importance of certain tile draws due to a lack of personal investment; I watched this series because it was given to me as part of an aniblogger secret santa pact, not because I was particularly drawn to it (although I did love Kaiji). The hard truth is that the plots of the first two arcs have very little to offer in the way of luring viewers into the story unless it’s through an interest in mahjong. More or less, the respective plots in both arcs just serve as an excuse to get players to the table and mahjong fans to the tube.

Were it not for the integrated yet juxtaposed efforts of the animation studios involved with Akagi, it would be easy to zone out during explanations of hands or the importance of certain tile draws due to a lack of personal investment; I watched this series because it was given to me as part of an aniblogger secret santa pact, not because I was particularly drawn to it (although I did love Kaiji). The hard truth is that the plots of the first two arcs have very little to offer in the way of luring viewers into the story unless it’s through an interest in mahjong. More or less, the respective plots in both arcs just serve as an excuse to get players to the table and mahjong fans to the tube.

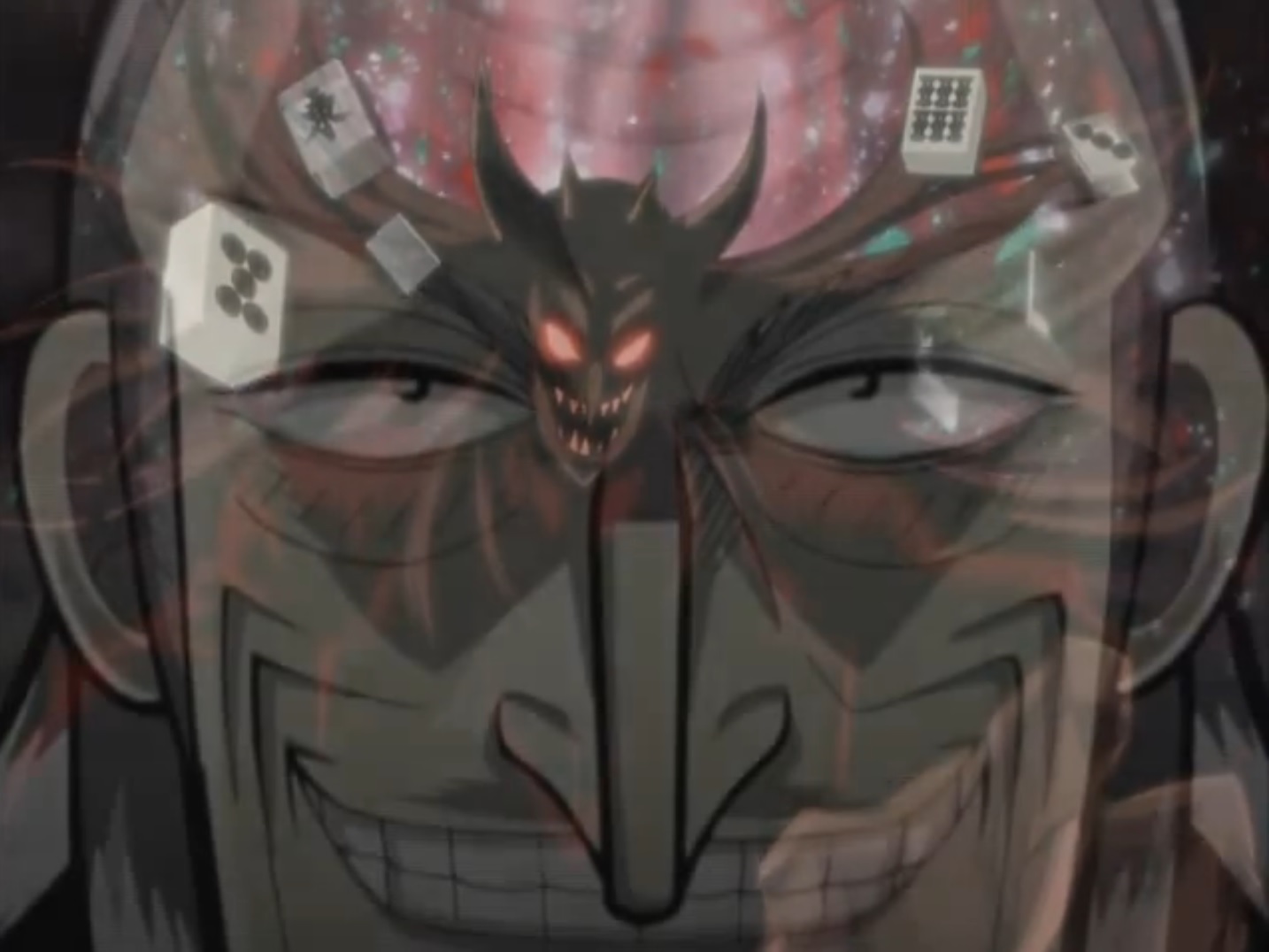

To maintain viewer focus and counteract the predicted apathy grown in response to extended match sequences, Madhouse offers up a very effective mix of stills, pans, sweeps, close-ups, split frames, and camera angles that dramatize people who are essentially just sitting and thinking 90% of the time. Hell, there are even some grandiose visualizations for characterization and metaphor. The rewards reaped from the employment of such animation tactics are most easily recognized within the last arc, which deals with the same setup for 11-some-odd episodes. Whether or not it’s done to replicate the dizziness of anemia, the “camera” takes full advantage of being ethereal to produce swooping shots between characters and throughout the room—with its elaborately decorated theme of sacrificial lamb and demon devourer—and thus adds life and vitality to what is, in reality, stagnant staging.

To maintain viewer focus and counteract the predicted apathy grown in response to extended match sequences, Madhouse offers up a very effective mix of stills, pans, sweeps, close-ups, split frames, and camera angles that dramatize people who are essentially just sitting and thinking 90% of the time. Hell, there are even some grandiose visualizations for characterization and metaphor. The rewards reaped from the employment of such animation tactics are most easily recognized within the last arc, which deals with the same setup for 11-some-odd episodes. Whether or not it’s done to replicate the dizziness of anemia, the “camera” takes full advantage of being ethereal to produce swooping shots between characters and throughout the room—with its elaborately decorated theme of sacrificial lamb and demon devourer—and thus adds life and vitality to what is, in reality, stagnant staging.

Integrated within the frame of Madhouse’s highly stylized visuals, based on art by Norihiko Yokomatsu (Kaiji) and designs of the original manga by Nobuyuki Fukumoto, Coxai Animation Studio’s contrasting CG (while not always so fantastic) creates a world within a world to both define the actual game of mahjong as its own element (as opposed to allowing it to be leveraged as a prop) as well as provide a certain visual shock factor that jolts audience into awareness each time the focus shifts from players to gameplay and vice-versa. The three featured tables offer different visual aesthetics and even sounds, the mahjong tiles themselves are lovingly rendered at every possible angle, and tricks with transparency and translucency sometimes made me wonder why I was drooling.

Integrated within the frame of Madhouse’s highly stylized visuals, based on art by Norihiko Yokomatsu (Kaiji) and designs of the original manga by Nobuyuki Fukumoto, Coxai Animation Studio’s contrasting CG (while not always so fantastic) creates a world within a world to both define the actual game of mahjong as its own element (as opposed to allowing it to be leveraged as a prop) as well as provide a certain visual shock factor that jolts audience into awareness each time the focus shifts from players to gameplay and vice-versa. The three featured tables offer different visual aesthetics and even sounds, the mahjong tiles themselves are lovingly rendered at every possible angle, and tricks with transparency and translucency sometimes made me wonder why I was drooling.

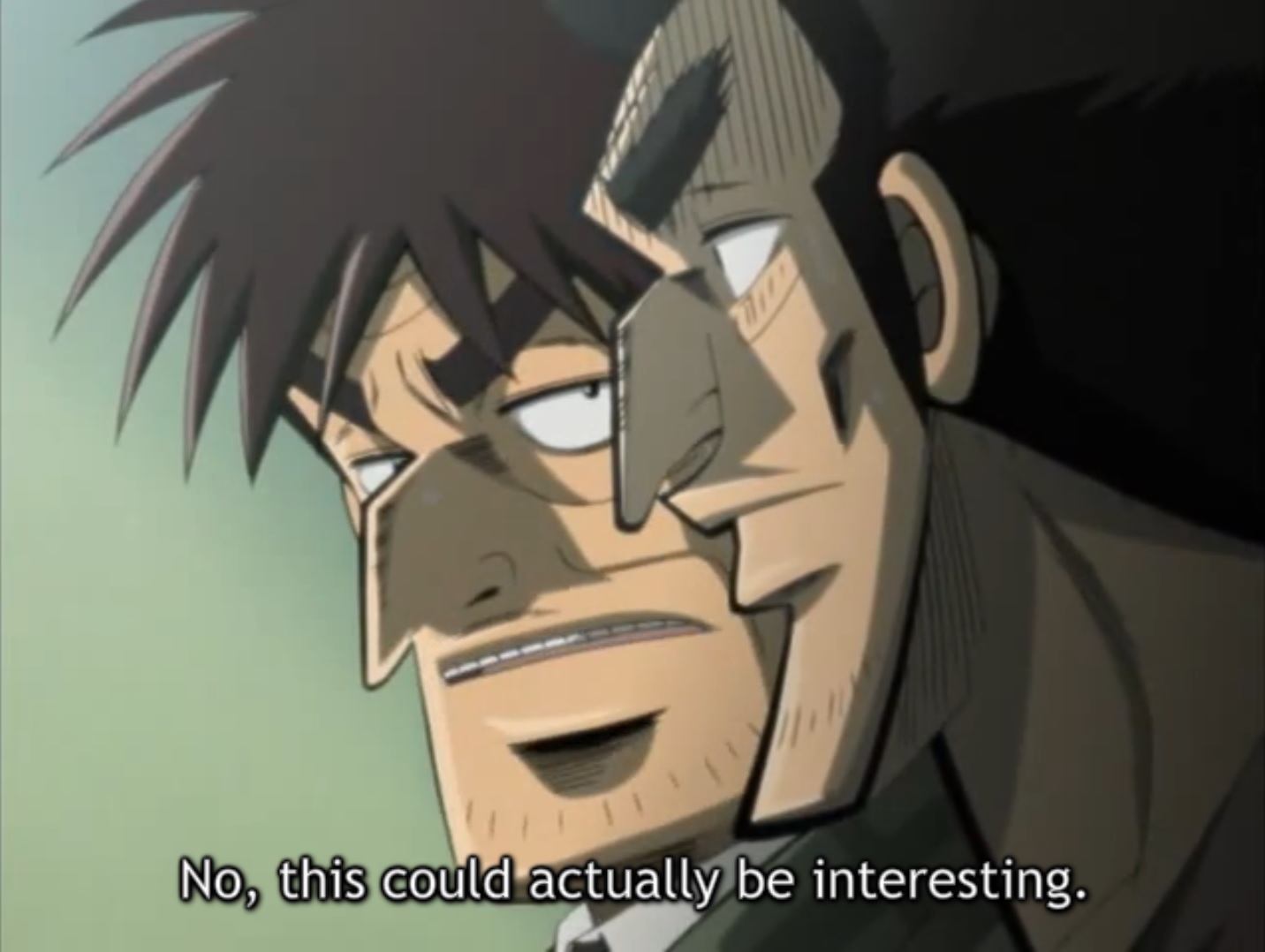

Characters are pretty flat, save the protagonist and maybe his last opponent; the last arc definitely steps things up in terms of pressure and (d)evolving sanity at the hands of id and ego. The plots behind the three arcs, as convenient as they are curt, fit very appropriately into a narrative as the defining exploits from a larger epic: the portrait of a legend. This series of encounters can also represent larger themes: luck vs. skill, purity vs. corruption, generational divides, but back stories, even within the third arc, are too shallow to warrant much speculation or reap justifiable epiphanies. That said, it’s always a good time watching a battle of wits, and that’s what Akagi delivers episode after episode.

Characters are pretty flat, save the protagonist and maybe his last opponent; the last arc definitely steps things up in terms of pressure and (d)evolving sanity at the hands of id and ego. The plots behind the three arcs, as convenient as they are curt, fit very appropriately into a narrative as the defining exploits from a larger epic: the portrait of a legend. This series of encounters can also represent larger themes: luck vs. skill, purity vs. corruption, generational divides, but back stories, even within the third arc, are too shallow to warrant much speculation or reap justifiable epiphanies. That said, it’s always a good time watching a battle of wits, and that’s what Akagi delivers episode after episode.

With direction by Yuzo Sato (Kaiji) and series composition by Hideo Takayashiki (Kaiji), Akagi is as much about beating the other player as it is about beating the other player’s hand. The plot is one-note, but the pacing and theatrics make up for that. The characters are flat, but they’re the kind of archetypes an audience can easily root for or vilify and have a grand time doing so … even if they don’t know a thing about mahjong.

With direction by Yuzo Sato (Kaiji) and series composition by Hideo Takayashiki (Kaiji), Akagi is as much about beating the other player as it is about beating the other player’s hand. The plot is one-note, but the pacing and theatrics make up for that. The characters are flat, but they’re the kind of archetypes an audience can easily root for or vilify and have a grand time doing so … even if they don’t know a thing about mahjong.

Akagi is currently streaming on Crunchyroll.com