Episode 10

Episode 10

Ink:Unable to face family or neighbors after Saeki serenades him with very specific questions of why from the street below his window, Kasuga instinctively bolts. Where he ends up and the person who’s there to greet him marks the start of Kasuga’s journey to THE OTHER SIDE. Ominous, isn’t it? Well, yeah actually. While comparing the manga to the animated goings on, I noticed two things. First, the cutesy is stripped from Nakamura’s manga self; her quips and verbal abuse less like playful banter and more like disparaging remarks that keep with the tone of both her character and the scene. Likewise, Saeki’s slow corrosion, caused by her Kasuga complex, comes off slyly and seamlessly thanks to Yoko Hikasa’s delivery of some key lines. Kasuga? He’s pretty much his indecisive self, but what’s great about this episode is that his waffling, or rather having to face it, becomes the device for his own breakdown.

As important as the visuals are to this series, something I’m sad that few have mentioned is the use of sound. Like the pacing and the rotoscoping, how the audio is employed offers a contrast perfect for exploitation. The better part of this episode is spent in the silence of a steady rain. That constant hush makes every labored breath, every bit of dialog, and, especially, each tortured scream all the more delicious.

David: I wasn’t falling over myself screaming like other anime blog types to evangelize the Flowers non-believers on the basis of this episode, but it was easily the strongest episode thus far that didn’t rely on shock value to carry it through the 24-minute runtime. Yes, it’s as close to cinema as most anime have dared approach in the last few years, but it’s not necessarily a good thing. I won’t deny that there are a lot of reasons to leap from your seat and applaud at what has been done with this episode. As conflicted as I am with the anime as a whole, I won’t hesitate to declare Yoko Hikasa’s Saeki as one of the best performances of the year. In the original manga, Saeki is mostly uninteresting and overshadowed by Nakamura. The Saeki in the anime, however, really comes alive as a character thanks to Hikasa rising above the limitations of her role as Kasuga’s muse.

Unfortunately, what this episode does reveal is that perhaps I may have given the manga too much credit for its writing, at least for the chapter in the mountain. I have a low tolerance for teen drama, and while Flowers aspires to be different at all costs, it momentarily becomes the kind of typical show it’s been trying to avoid. The only reason there’s any credibility in the angst, delivered with a seriousness bordering on embarrassing, is Hikasa selling her part with all her heart and the presence of Nakamura to bring everyone back down to reality. The animated Flowers has carefully cultivated a reality for its interpretation of the manga that once it brought in a more cinematic direction for the scenes in the mountain, it feels unreal, not in the sublime way as in the end of episode 7.

Unfortunately, what this episode does reveal is that perhaps I may have given the manga too much credit for its writing, at least for the chapter in the mountain. I have a low tolerance for teen drama, and while Flowers aspires to be different at all costs, it momentarily becomes the kind of typical show it’s been trying to avoid. The only reason there’s any credibility in the angst, delivered with a seriousness bordering on embarrassing, is Hikasa selling her part with all her heart and the presence of Nakamura to bring everyone back down to reality. The animated Flowers has carefully cultivated a reality for its interpretation of the manga that once it brought in a more cinematic direction for the scenes in the mountain, it feels unreal, not in the sublime way as in the end of episode 7.

Episode 11

David: After the kids had their fun in the mountain, of course the adults are not too pleased to see them sitting in the back of a police cruiser. The strain placed on Kasuga in particular is palpable as his classmates ostracize him further and Saeki breaks up with him in the most impersonal manner. It’s miserable to witness Kasuga crushed down to nothing but it’s only natural for the world to stamp out any abnormality.

If it wasn’t obvious ten episodes ago, Flowers of Evil is not something I would consider fun to watch. It doesn’t have to be. Even though the show follows the manga to the letter, it’s such a different experience watching it as opposed to reading it that it’s incredible what a few extended scene takes and silences can do for the mood. I can tear through chapters of the manga effortlessly but the anime denies me that, forcing me to savor the gloom. I’ve already professed my love for long scenes of characters walking, so while I wasn’t convinced to ride the Flowers bandwagon after Episode 7 or Episode 10, the dream sequence at the end of this episode has me open to change my opinion depending on what comes next.

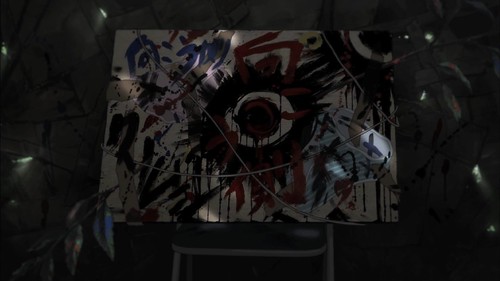

Ink: If it’s natural for the world to stamp out any abnormality, it’s just just as natural for abnormality to survive in order to be stamped out thus. So the seeds long since germinating in Kasuga’s head take firm root thanks to Nakamura’s fertilization and increased public obstinance regarding the authority of a town which has cultivated such resentment via dissimilarity and disapproval. There’s no sceencapping the wonder that is the ecstatic flurry of evil which fills Kasuga’s dream of saving Nakamura from her social isolation. Then again, if every potent moment could be relayed via a still, then what difference would there be from the manga? And oh what a difference there is.

Though David describes this series as something that’s not fun to watch, I’d agree in that fun is far too shallow. Flowers of Evil is delicious. Those extended moments convey so much, like how Kasuga’s asking to be excused from the dinner table turns into a subjugated apology. How in the minute or so after he leaves, his empty chair becomes the focus of the scene, and his mother and father sit silently, as if in conversation with that emptiness, talk in a stillness that betrays the mother’s disappointment in her son and self and the father’s enabling escapism

Episode 12

Ink: THRILL as you watch Kasuga write and read (silently, to himself) an essay! No, seriously. Revel. It’s a scene that starts off with a full minute of absolute silence — no noise at all, but a sense of inner tension aptly wrought via contrast with the recap’s fury — and ends with Kasuga’s rebirth to the world. The latter is accomplished by a distinguishing shot of Kasuga opening the window, his visage nigh unrecognizable due to the rotoscoping and camera angle.

At school and after, everyone’s moving on without Kasuga, and he’s, at the very least, peripherally aware of it. The most interesting instance of this is Saeki gabbing with her friends, which includes specific movements and dialog that deepen what’s offered in the manga and add a lovely sense of hurt and spite to her character. Kasuga is also moving on, finally choosing his own path (out of guilt and misguided sense of empathy) and walking/running it. This newfound determination directs him to Nakamura’s domicile, where he gets cosy with and learns about her family (Yuto Nakano deserves an Emmy for his portrayal of the disheartened father), is railroaded into accepting a dinner invitation, and turns Nakamura’s bedroom doorknob with the same trepid yet gravitational curiosity as he once reached for a bag of gym clothes on a classroom floor.

At school and after, everyone’s moving on without Kasuga, and he’s, at the very least, peripherally aware of it. The most interesting instance of this is Saeki gabbing with her friends, which includes specific movements and dialog that deepen what’s offered in the manga and add a lovely sense of hurt and spite to her character. Kasuga is also moving on, finally choosing his own path (out of guilt and misguided sense of empathy) and walking/running it. This newfound determination directs him to Nakamura’s domicile, where he gets cosy with and learns about her family (Yuto Nakano deserves an Emmy for his portrayal of the disheartened father), is railroaded into accepting a dinner invitation, and turns Nakamura’s bedroom doorknob with the same trepid yet gravitational curiosity as he once reached for a bag of gym clothes on a classroom floor.

David: Can I talk about the scene in which Kasuga chases after Nakamura, reciting his essay all the way up until Nakamura gets away? It’s obviously CG. It has to be, right? Pausing at any moment of the scene and the fidelity and angularity of the shapes give it away. The shots are blurred to hell and the camera shakes the whole time. I should hate animation like this, but no, it really works here. On one level, there’s the rotoscoping. Then, a virtual camera is faked to correctly track the rotoscope animation while moving in the CG environment. The entire exterior Kasuga and Nakamura run-in needs to be recreated in CG, textured just right to match the look and feel of the show. If you’ve been paying attention, Flowers has some ridiculously detailed interiors and exteriors, so following two character run around town blows through a lot of art assets that may only be seen for a second before they’re out of the shot and never used again. Putting it all back together, what we have is an animation of characters traced over from live footage, running through a computer generated environment, filmed through a virtual camera mimicking a real camera. In an effort to render this scene as it actually happened, the animation removes itself so far from reality that it ends up coming back full-circle. Thematically, the end of Episode 7 illustrates best what the show is about, but on a technical level, this scene defines Flowers of Evil.

Episode 13

David: Right to the very end, Flowers of Evil remains hateful of its audience, reserving one final trick that’s so fantastic that it makes me wish there is never a second season. As someone caught between liking and disliking the animated series, I’ve had a rough time pinning my opinion down, even now after it’s all over. I’m not in love with the vision behind the show but I respect it for sticking with it the whole time through, for never apologizing, for flat-out denying anyone coming in with expectations for this adaptation. I wanted to either shriek praises fanatically or bitch and moan endlessly by this time, but all I can offer is slack-jawed awe.

The greatest problem Flowers has is that it’s one of those shows that doesn’t get good until Episode X (Episode X being Episode 7 in this case), which doesn’t work since Flowers relies on that first half to build up towards the best scenes in the show. There is something satisfying about seeing the animation and direction improve by leaps and bounds as the show goes on, and some scenes in that divisive first episode show glimpses into the potential of this adaptation. However, that first half is such an awful drag that it almost doesn’t make it worth watching to get to the second half. Flipping off a pampered audience in the name of art is fine, but it gets old after two hours.

I find Flowers difficult to recommend on the basis that it’s the right story in the right medium with a very limited spread of people who would be capable of appreciating a show as abrasive as this. The manga is an easy sell and an easy read, but the anime is a revelatory adaptation that wrings the material dry, drip-feeding the viewer every last detail at an agonizing rate. Flowers of Evil is a demanding show that only works depending on how much you hate cartoons from Japan and yourself.

I find Flowers difficult to recommend on the basis that it’s the right story in the right medium with a very limited spread of people who would be capable of appreciating a show as abrasive as this. The manga is an easy sell and an easy read, but the anime is a revelatory adaptation that wrings the material dry, drip-feeding the viewer every last detail at an agonizing rate. Flowers of Evil is a demanding show that only works depending on how much you hate cartoons from Japan and yourself.

Ink: It’s hard to call this end as either hateful or benevolent. While the series missed a viable stopping point, it did so only to honor its own sense of pacing. And as I have been in constant praise of such, I therefore cannot rebuke it. The end that is given is the one that the audience needs, not necessarily the end they deserve. With the sixth volume of the manga still pending and nothing but possibility posed to followers of the series, the track taken by this final episode issues equal points closure, frustration, amazement, and intrigue. David makes it sound as though there’s not a drop left to be wrung from the source material, but there’s so much more in store that it would be impossible to render the effects of the adaptation thus far as impertinent should this animated adaptation continue.

I yearn for a second season. I hope there’s never another season; this 13-episode run was near perfect aside from what amounts to minor nitpicking, and I fear for what might impugn the obstinate purity of this run should another season have a go. Even without telling the rest of the story, this adaptation has told so much more than its source material in its respective time frame, and I am grateful for every labored moment.

I yearn for a second season. I hope there’s never another season; this 13-episode run was near perfect aside from what amounts to minor nitpicking, and I fear for what might impugn the obstinate purity of this run should another season have a go. Even without telling the rest of the story, this adaptation has told so much more than its source material in its respective time frame, and I am grateful for every labored moment.

I do not think Flowers is nearly antagonistic to its viewers as David claims, but he is right in that its audience is a niche one: those with great patience, an appreciation for atmosphere, and a penchant for wallowing in the moment. If you like to sink, you’ll love these 13 episodes. If you love to think, about how surroundings affect characters, how characters affect their surroundings, and how surroundings betray us all, then you’ll love these episodes. If you want to question yourself as much as that which you are watching, do yourself a favor and watch these 13 episodes. They’re looking at you, and after you look back, no amount of moé will save you.

Flowers of Evil is now streaming on Crunchyroll.