Manga Editor Yumi Sukemune on Making Princess Jellyfish and the History of Shojo

The editor discusses her decade-plus career in manga and the feminism of <cite>Sailor Moon</cite>.

Most writing about manga focuses on the artists and writers credited on the covers of the books. But there’s another role that’s indispensable to the creative process for most manga series: the editor. In addition to managing the manga production schedule, editors provide creative guidance for artists, in some cases acting as equal partners in coming up with the storylines and characters of their series.

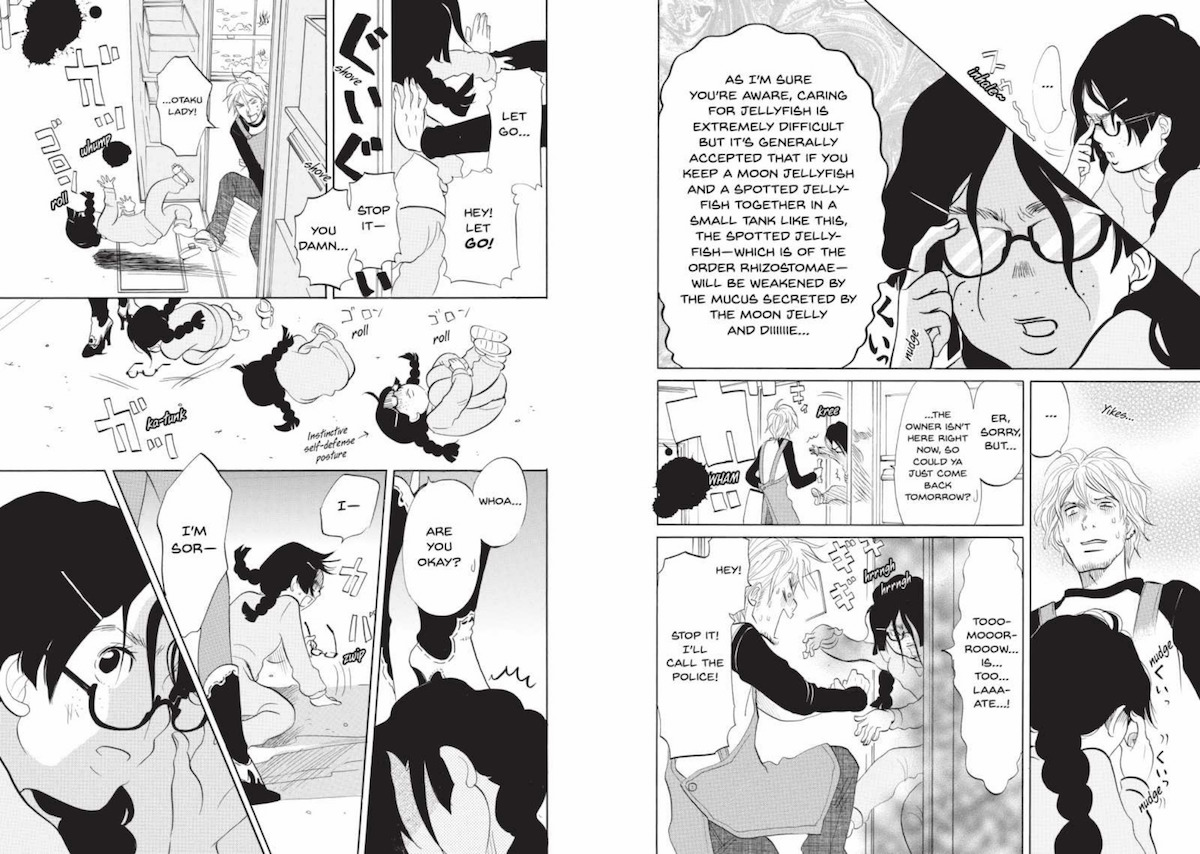

A year ago at Anime Expo 2017, I sat down with manga editor Yumi Sukemune to chat about her work with Akiko Higashimura, the artist behind the josei (adult women’s manga) series Princess Jellyfish about a group of geeky women living together in a Tokyo apartment complex. But our conversation wandered a bit outside of her day job, revealing an editor with a critical, feminist perspective on the history of shojo (girls’ manga).

Thank you to Ms. Sukemune and Kodansha interpreter Misaki Kido for the interview opportunity, and for their patience as this interview sat in draft form for an entire year. It took a while to get this one out, but I think it was worth it!

First off, how did you get started as a manga editor?

I joined Kodansha 12 years ago right out of college. I’ve been assigned to the Kiss Magazine Editorial Department the entire time. The editor of Attack on Titan joined Kodansha the same year.

What titles have you edited?

Princess Jellyfish and Tokyo Tarareba Girls, which is Higashimura’s follow-up series about 30-something-year-old ladies. It’s like a Tokyo version of Sex and the City. A lot of titles that aren’t published outside of Japan. I always have five to six titles that I’m looking at at any time.

How typical is it for a manga editor to be editing multiple titles at the same time?

It’s pretty common.

What’s the process for how editors are assigned to titles?

For those existing series, there might be editors already assigned to them, but in Japanese companies, people rotate from department to department fairly frequently. So when some editor leaves the department, if the title needs a new editor, then that’s an opportunity where you might get assigned to an existing title.

In my case with Higashimura, there was another editor before me, but then that person left. But besides that, I was already close with Higashimura because we both liked Johnnys idol groups. That was our connection.

So when the previous editor left, because I was pretty personally connected to Higashimura, I became the editor.

Is Higashimura going to do an idol series?

(laughs) She loves K-Pop right now.

Being an editor is a creative role in addition to an administrative one. Is that assignment process partially based on story fit in addition to being good at managing an artist?

There’s no test for it or anything like that, but when you’re being hired into the company, in the interview process, they’re looking at the way you talk, the way you express yourself. The people looking for new hires are picking up those kinds of personality traits. So those are some of the challenging aspects.

In other cases, when you first start to become an editor, you team up with more of a veteran, “sempai,” editor. Then, when they go together to a creator’s house and they have a meeting, the sempai editor will ask you things like, “What would you do in this case of the story?” You’re on the spot and you have to express what your opinion is.

A lot of the editors love manga of course, but they also study and watch a lot of movies and stuff like that too. There are a lot of movie otaku.

I imagine they read a lot of books too.

Yes.

So in terms of the creativity, of course there’s individuality, but at the same time … being in love with the character, that’s just being a fan. As an editor you have to really think about where the story’s going: beginning, middle, and end. You need to look at it constructively and then put your opinions into those critical perspectives. That’s something that’s expected from an editor. And then, depending on your level of skills in addition to your creativity, you could become a hit-maker editor or not.

The Manga Editing Process

What’s a day in the life of a manga editor like?

My working hours are flexible. Most of the manga artists work at night. So in the morning, a lot of people just watch movies and things like that. Around noon-ish, that’s when we go to work. But then we won’t be able to go back home until the last train.

In terms of shojo manga artists specifically, it’s kind of a one-on-one relationship of manga artist to editor, so as long as we can stay in touch with those artists, we can work from anywhere. We can work from home too.

Regarding Higashimura, she works on so many series at once, but she also has a lot of assistants and they’re kind of set up like a studio. Their schedule usually starts at 11 AM and goes until 7 PM. So in terms of Higashimura, she definitely doesn’t work beyond those hours. She won’t pull all-nighters, she won’t work on weekends. She keeps a work-life balance.

Do a lot of very successful manga artists do that?

It’s not regular at all!

Because it’s set up like a production studio, the main artist Higashimura just does the rough sketches for the story and she also does the penciling. But from there on she actually works with other staff, and they finish her work.

When the artist sets up a production studio-type of setup, then they can actually work on more than just one title at a time. But not too many female artists actually do it like that. Usually if you work with shojo manga artists they’re working with their friends and just barely making the 30 pages each month.

You mentioned in the Kodansha panel earlier that Ms. Higashimura is the most prolific current shojo manga artist. That she has the most titles.

That’s true. She works with all the major publishers.

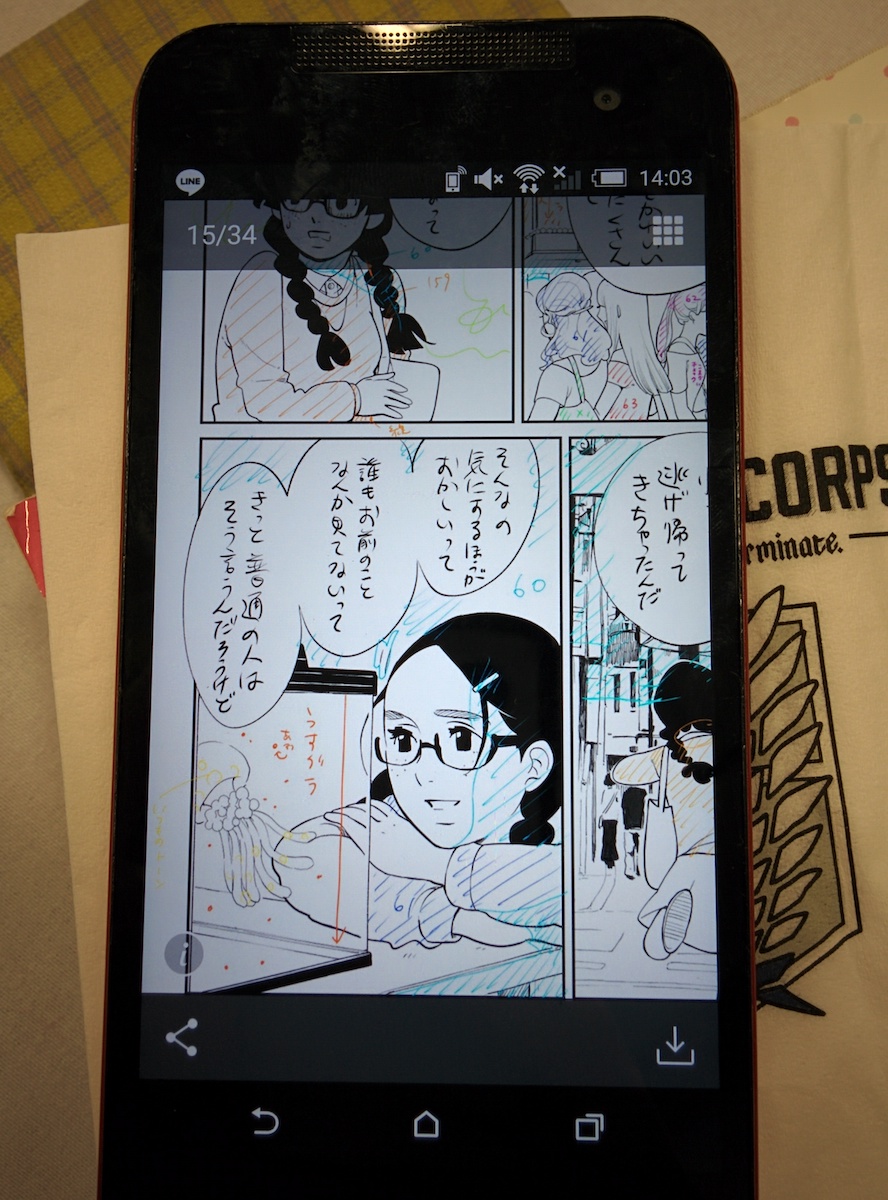

Speaking of staying in touch with artists, we were looking at your phone before. Could you talk about the process? You two are on LINE sending “names” (rough manuscript drawings) back and forth, right?

(She shows me her LINE message history with Ms. Higashimura.)

Yesterday Higashimura sent a name. I usually just loosely say “I kind of want to see the first draft by this day.”

The name stage is usually very simple. But for her, she makes it very detailed. This one has notes on how to finish these panels for the assistants. So, “Put the shadow on here, on the blue.”

Here’s what I’m saying in these messages: “Sorry about the delay of this post. I think the name is really awesome. I think we can use it just the way it is. Especially the scenes in the past and the scene about grilled fish. You’re actually connecting them indirectly. I think it’s really well done. I am here in LA in the morning. I was in awe for a minute. If you’ve got a continuation of these pages please send it to me.”

What stickers do you use on LINE?

We mostly send photos. Not a lot of stickers.

(She shows another name with red pen marks on it.) This is proofing. I use red pen to mark things.

Princess Jellyfish is a really honest portrayal of fujoshi and otaku culture and social anxiety. What sort of conversations do you two have about telling this kind of story?

She often models these characters off of her real-life friends. There’s a friend of hers who’s into dolls. Also all her assistants are super manga otaku. While they’re working, they’re always chatting, for example, having a funny conversation with different ways to end a sentence. The way they talk is unique. She picks it up while she’s writing. Whenever I meet her or even on LINE, Higashimura mentions, “Oh this funny thing happened.” I say, “That’s really funny, why don’t you write about it?”

Communicating and keeping friendships with people outside of work is one of the main reasons she insists on doing the 11–7 shifts, the work-life-balance. Tokyo Tarareba Girls is really based on all her friends who are editors, who are always bitching about something. It’s like, “I’m working so hard, but I have no boyfriend. What’s going on?” She writes about that.

As her editor, my main job is to figure out what she’s into, what her main focus is right now, and to encourage her, to ask “why don’t you write that into the story?”

Shojo and “Waiting for Men”

In the panel earlier you talked about how shojo has changed. You said it was about waiting for a boy to discover you, and now it’s about girls saying “this is my way of life.” Why do you think that is?

I think the biggest influence was Sailor Moon. I’m 34 now. When I was little, Sailor Moon was a current, ongoing series. Up until the emergence of Sailor Moon, all the manga was really about an average girl being discovered by a boy. That was the classic formula. But as soon as Sailor Moon hit, everything changed into a new generation of girls who had the ability to do what they wanted to do in life.

Around that time in the history of Japan, women were starting to get accepted into regular workplaces. The timing in history might have contributed to the message too.

For those girls who grew up with Sailor Moon and keep that true to their hearts, as they get older they become these really strong women and do things for themselves.

Do you think the cultural shift influenced Sailor Moon? Or the other way around?

Sailor Moon was originally supposed to become an anime by the time it started. There was a project for the anime too, they worked on them together. So instead of waiting for the stories to finish, they actually continued the story at the same pace in manga and anime. Because it was a collaborative project between the artist and the animation studio, it wasn’t really up to the creator herself. The creation came from the anime production team as well.

Princess Jellyfish is josei though, not shojo, right?

Yes. The magazine is a josei magazine, although story-wise, none of them are working, so it’s more in the realm of shojo manga, really. And definitely the style is shojo manga.

How much of what you were describing about shojo applies to josei?

In the josei manga genre, unlike shojo manga, it’s not all pure and fresh. It’s not that kind of puppy love story. But in terms of the main character opening up the door to their own life, it’s actually consistent between both shojo and josei manga.

Was josei already doing that, though?

Even in josei manga back in the day, even though they were working women, the formula of an average woman being discovered by men was still the same. It’s like all the characters are mature adults, but it’s still this bubbly romance.

There’s a series called Tramps Like Us (Kimi wa Pet) in Kiss Magazine. It’s a story about a girl picking her favorite boy and keeping him in her house. The pet is a boy.

That change is interesting. Early shojo manga like the works of the Showa 24 Group weren’t about women waiting for men.

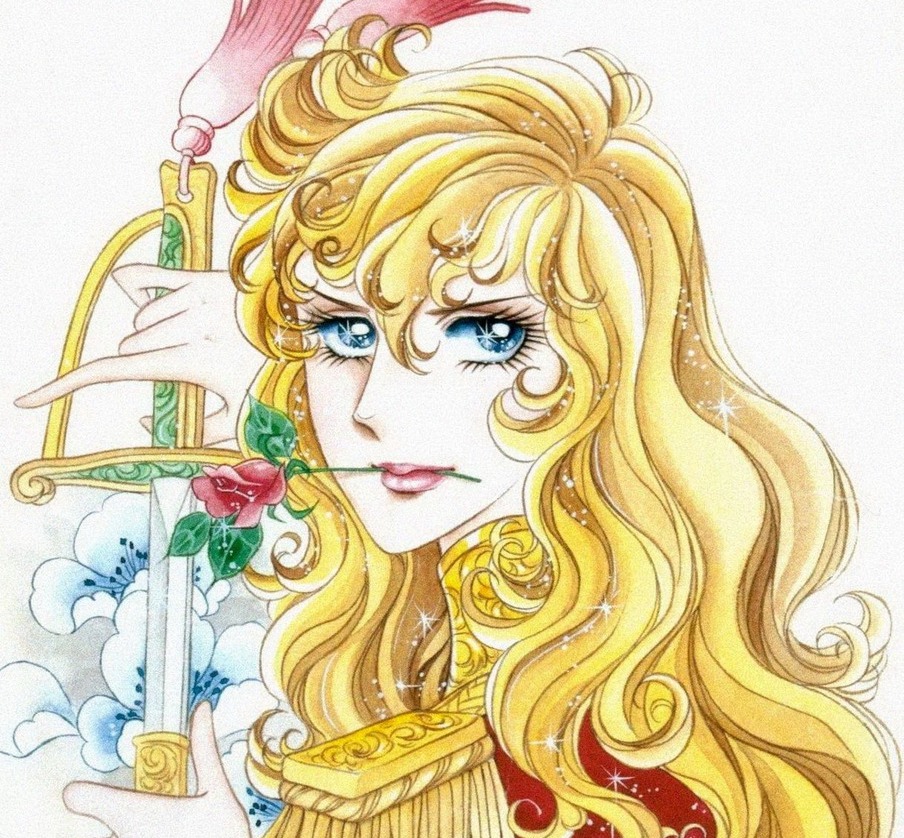

Those series like Rose of Versailles are very eternal, evergreen titles. Those tend to be the formula of the character seeking their own path. Those legendary creators: Keiko Takemiya, Moto Hagio. Series that actually stick around long enough to be classics, they tend to be based on main characters finding their own path. But series that became very popular hits but eventually as time goes became lost and forgotten, those are the ones with the formula where the girl gets discovered by the boy.

I feel like in the 1980s shojo manga went in that direction a bit.

Yes, during the bubble economy. Back in the ’80s during the economic boom, it was all about what kind of relationship can you have as a person. That was the biggest focus.

Keiko Takemiya was told by an editor that a story was not going to be a hit; it was complicated, it should be more romance. But she really felt strongly about writing those kinds of stories. So she created The Poem of Wind and Trees (Kaze to Ki no Uta) from there. It’s a really famous Boys Love manga now.

It really shows how hard it was for those female creators in the ’80s to stand up for what they wanted to write about and to execute their expression and get published.

There have been a lot of fans who have been supportive of creators like Takemiya, but at the time, those fans were a way smaller fraction of fans. But post-Sailor Moon people began to accept and understand and like those formulas too. In terms of The Rose of Versailles, it’s inspired by the sort of “fantasy” admiration toward French culture. So that brought in the audience. It’s not really because of feminism. It’s because France is cool.

But it sounds like Sailor Moon represents more of a true feminist shift.

I think so.

There’s an element of romance in Sailor Moon with Tuxedo Mask but that’s not the focus of the series and that’s not the reason why she’s fighting. She’s also looking out for her teammates and friends.

In the US a lot of fans had a very similar response. Because we didn’t get a lot of female characters with that kind of agency.

Everything is connected. No matter where you’re from you really want to cherish and respect yourself in terms of your personality.

As an editor, I always question the difference between the audiences. Like, the school life in America and Japan is different. Is that something that affects the popularity of manga?

The portrayal of the cool, attractive boys seems to be very different here in the US too. I think that might affect whether a manga series becomes popular overseas, not just in Japan. Series like Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura, ones set in fantasy-based worlds, are kind of rare in shojo manga. They’re just a fraction, and the rest of the titles are focused on school life and slice-of-life stories.

Even the editors and executives in Japan, they’re thinking that whatever is available here and the shojo manga outside of Japan is just a fraction of the shojo manga that is available.

The High School Formula

Have you edited any of those high school titles before?

I have a series called Love’s Reach. In shojo manga, there are a lot of teacher-student relationships, but elsewhere that’s illegal, right? Love’s Reach is the standard shojo manga formula: school life, always a big event with some emotionally thrilling moments. So if people actually get into these series and accept these kinds of stories then we can introduce a bunch more shojo manga. A lot of the shojo manga that’s available here, like Princess Jellyfish or Nana, is kind of irregular compared to the rest of the shojo manga in Japan.

Is there anything different about editing for one of those school life series versus something more irregular?

For Princess Jellyfish, the creation starts with Higashimura’s inspiration, ideas, and imagination. In terms of things like Love’s Reach, there’s the standard formula and then you put a good talented artist on it. So during the meeting, I say things like “do you want to go on a school trip now?” Like, “this is a good time now.” We have these formulas so you can sort of test the artist to see if they can work creatively with those frameworks and make them their own. That’s how each of the creators’ talents emerge.

Because the history of shojo manga is so long in Japan, there are readers who just want to read a formulaic story. Instead of going into a really fresh story that’s very imaginative, some people just want to read the same old story right before they go to bed after coming back from a long day of work.

In fact, a lot of the digital shojo manga sales in Japan happen after 11 PM. It’s interesting. They probably just buy it and read it and just fall asleep. Maybe right before you’re going to bed and you’re relaxing, you might not want to be introduced to super fresh, super imaginative ideas.

(laughs) The Rose of Versailles is too heavy!

(laughs) I might dream about it or something!

Of course sexy titles and “ero” manga too. Manga that you don’t want to have as a book also sell during nighttime.

It’s important for big publishers to fulfill all these people’s needs. Of course we want to create something new, but we also want to produce something that our audience would want.

Thank you so much for your time!