Jason Rohrer on the Emergent Game Storytelling of One Hour One Life

The solo developer discusses his ambitious thought experiment-turned-game and the economic development of its player-driven world.

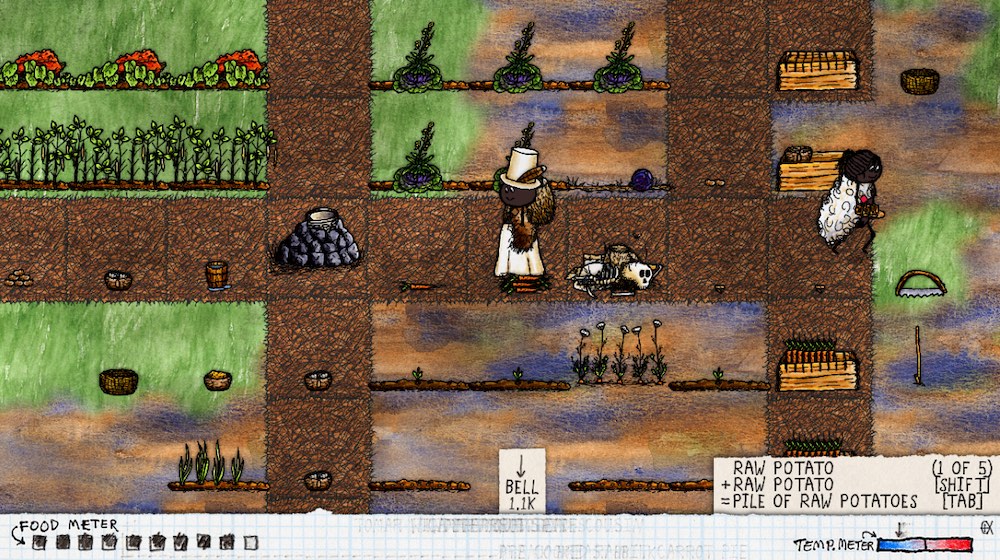

One Hour One Life is one of the most fascinating video games I’ve played in years. It’s a multiplayer online game in a persistent world full of resources that players can harvest and craft into tools, not unlike Minecraft and similar games. But the twist is that every player (with rare exceptions) is born into the world as the child of another player and lives for only 60 minutes from birth to death. Together, players have collaborated across generations to build thriving civilizations, making use of a massive tech tree created (and updated weekly!) by the game’s solo developer: Jason Rohrer.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Rohrer (virtually of course) last week for an in-depth interview covering One Hour One Life and the philosophy that underpins his ambitious creation. Rohrer is fascinating in his own right. Since he made waves with his short 2007 game Passage, he has consistently pushed the boundaries of interactive storytelling and social video games. I first came across him through Sleep Is Death (2010), a collaborative story-making game played between anonymous online players. The Castle Doctrine (2014) explores Rohrer’s anxiety about home invasion by forcing players to turn their homes into death traps before setting out to rob the homes of other players. His work often feels paradoxical; at once inspired by Rohrer’s personal experiences and driven by a precise, highly analytical approach to game mechanics and player behavior. He’s also a somewhat polarizing figure, staking out positions on politics and the game industry itself that can be unpopular among his peers.

This article contains a transcript of roughly half of the full interview, since we ended up having quite a lot to talk about! In the transcribed portion we cover the connection between the COVID-19 crisis and One Hour One Life, the importance of true “social” gaming, the thought experiment that inspired the game, and the lack of player-driven commerce in the game world. In the full interview, available in podcast form for $5 subscribers on the Ani-Gamers Patreon, we go even deeper on all of these subjects, and even delve into a fundamental political disagreement between Rohrer and many of his players (myself included).

That’s more than enough preamble, I think. Enjoy!

Ani-Gamers: Considering world events right now, I wanted to start with how COVID-19 has influenced your thinking around One Hour One Life.

Jason Rohrer: I thought a lot about diseases in the game long before this. And of course now everyone is like “why aren’t there diseases in the game?”

Ani-Gamers: There’s yellow fever, which you can get from mosquitoes.

Rohrer: Yeah but it’s not communicable. It’s been a long time since I added that disease to the game and I did study it at the time and I don’t remember all the details, but I got the impression at the time that it’s a mosquito-borne disease and that it wasn’t contagious from person to person so much. Although maybe I’m completely wrong about that.

But anyway, communicable diseases are interesting from a simulationist point of view. It’d be an amazing experiment to introduce communicable diseases into the game and see how people react, but I don’t think on the ground it would be that interesting to the players because it would swamp all other aspects of the game.

Ani-Gamers: It would become a disease control game.

Rohrer: Yeah. If you go to this village and you see people with the visible signs of the disease — whatever it is — and then you interact with them and you come back to your own village and then people don’t let you in. It would just swamp everything. And then also does disease become eradicated over time and if so where does the new one come from? Do I as the god of the world periodically introduce diseases and watch as they run their course? Maybe it would be an interesting event for players, but it also feels like that’s not what the game is about.

Ani-Gamers: In terms of the response to COVID-19, one of the things I’ve noticed is that the lockdowns highlight how much of our lifestyles and production are social. I think the game does a very good job of showing that.

Rohrer: Right, right. A lot of what I’m trying to do in One Hour One Life is, ironically, especially with all the design changes I’ve made over the past couple of years, sort of force people to be social. Well, not social, because when we say “social games,” we imagine you have a game with a chat box attached to it, or you play the game on Facebook and your Facebook friends somehow play in parallel with you or you’re competing on a leaderboard with them.

Ani-Gamers: It’s latching onto an existing social network.

Rohrer: Yeah. It means “we’re going to be chatting in these games.” That’s not what I mean by social. What I mean by social is that what other players are doing in the game matters to you in terms of what you’re doing and that somehow they become actually important characters in the game that you’re playing. Not just as chat partners, to get in there and talk about what’s going on in the election or whatever in real life.

Think about it, the role of NPCs, non-player characters in most single-player games. Think even about a simple example that everyone is familiar with like Zelda. Not the original Zelda, but Ocarina of Time where there are a lot of NPCs around and a lot of quests and things that go on in the game that involve these NPCs. I don’t remember the details of a particular quest because I haven’t played the game in so long but I’ll just make one up. Something about a guy who’s got a milk farm or something and there’s some kind of horse racing thing. There’s something about having to bring someone some fresh milk. So you’ve got to go to some other NPC somewhere in the world and convince them. They’re sick and they won’t come out or whatever and you have to bring them this medicine. Then they give you the fresh milk and this guy won’t let you race unless you bring him the fresh milk and so that is a social interaction. That’s social gameplay. Not that there’s a real intelligent social entity at the end of it but it’s simulating the experience of “I need to interact with these people in the world in order to accomplish this thing that I’m trying to accomplish and sometimes they’re angry or grumpy and I need to figure that out.” It’s very rudimentary, the emotional gameplay that’s present there. This guy’s sick or he’s angry and I need to make him happy. It’s almost a key and a lock that’s dressed up as some kind of social interaction.

So One Hour One Life has the potential to have that kind of thing happen, but for real. You’re not just looking for a key and a lock because the character you’re interacting with is a complex, fully intelligent entity who is another player. The problem is that it’s very easy for the game to degenerate into situations where those kinds of interactions aren’t even necessary. That’s sort of the default grain of this “multiple people in a world where you’re crafting and building things” game. Players put blinders on and figure out how to build what they want to build and then build it.

Ani-Gamers: You mentioned in other interviews that playing Rust felt super individualistic.

Rohrer: Yeah there are all these other people around but they’re either trying to get you or ignoring you or whatever. There’s no social structure that built up. There’s no sense of a neighborhood that built up. Every once in a while you would interact with one of your neighbors in some way, either a negative or positive interaction — every once in a while it was positive. But there wasn’t a sense that we were banding together in any kind of way to cooperate or to trade or to build any kind of legal system or de facto way of doing things. We were all on our own little beeline quests passing like ships in the night, occasionally firing one across the bow at the other guy.

One Hour One Life has the potential for that, or that’s what I was always imagining. You’re in these situations in part because you don’t just keep playing and playing and playing forever and ever and ever working on your personal project. Because you die after an hour you at least have to interact with somebody in the game, which is the next generation, to raise them. Because if you let all the babies die — that’s the fundamental premise of the game — if you let all the babies die then everything you’re building in your lifetime is lost.

Ani-Gamers: Plus you have to interact with your own mother.

Rohrer: Right or you can’t get to the point where you can work on your own personal project. That little fundamental wedge in the game at least ensures some social interaction. But beyond that what I was seeing was literally you get to age three where you can feed yourself and the common thing — it’s almost risen to the level of a meme — was for your mom to say “glhf” or “good luck, have fun.” Slap a hat on you, make sure you’re all set, maybe hand you a pie or something and say “good luck, honey.” And never see your kid again necessarily. You don’t really care what happens to them after that point, so much, as long as some of your babies survive. If every single one died then everything would be lost. Then players go off on their own beeline quests and don’t really interact.

So a lot of the stuff I’ve been doing recently has been — it’s a dangerous tightrope to be walking on where you’re like “the players aren’t doing what I want them to be doing. So how do I force them to do it?” (laughs)

A simple example more recently is the idea that you can’t learn every single tool in the game. There are 25 or 30 different things that are marked as tools that require some kind of expert skill to use. And you can only master so many skills in your life before you start to run out of mastery slots. So you have to pick and choose what kinds of things you focus on and if you’re building something more complicated, you’re going to need more mastery than you yourself possess. And at that point you literally have to walk across your village and find the guy who knows how to use the tool you don’t know how to use to finish the thing you’re working on and say “hey buddy can you come and use this blowtorch.”

Ani-Gamers: How much of the game is an experiment where you see yourself as setting things up and seeing what happens, and how much are you trying to teach the players something? Are you trying to get the players to walk away having learned something about humanity or society or the way that production works?

Rohrer: It’s funny, I guess I’d say it’s neither of those things. I’m not interested in teaching anyone anything. Even going back through my career, it’s not really “hey I want to make you have this realization about your real life” as much as i want to provide you with this interesting, compelling, emotionally evocative experience. And some people apparently do have realizations about real life when they have that kind of experience, but if that’s your goal as a designer … It’s sort of a spoonful of sugar to help the medicine go down. You want to have this valuable experience that has a take-home message. (laughs) To me that feels less like art and more like a lecture or something. So I’m not intentionally trying to do that.

On the other hand I’m not intentionally trying to set up some sort of experiment and like a mad scientist, just see what happens. I’m more, as a designer, trying to almost predict or fashion this thing that will hopefully work in the way I want it to work to create the most interesting, rich kind of experience and situations that I can imagine a video game producing. So it’s more like me predicting, “ooh, if I add this kind of wrinkle into this situation it’s going to trigger these kinds of interactions.”

It’s never as cut and dry as “walk over to this guy, tell him you need a sheep slaughtered and he just instantly goes over and does it.” Maybe he’s busy, maybe he doesn’t like you, maybe he’s got something else on his mind, or maybe this person just had a baby, or whatever. They’re too busy with something else. And so it’s not as simple as just a key and a lock. If we describe the system in words and say “you only have a limited number of tool slots and if you need something else done you gotta get someone else to do it for you” that sounds kind of like you just need to go through this motion, walk over there and get this other person to do this thing for you, but it’s never quite as simple as that.

Ani-Gamers: Because they’re all real people.

Rohrer: Right.

Ani-Gamers: How does the goal of creating these emergent emotional player stories interact with or even conflict with goal of realism, of recreating how actual human development worked?

Rohrer: A lot of people think this is a civilization simulation game where it’s like “let’s start with cavemen and get up to present day.” As far as I’ve conceptualized the game, that’s never been what it’s about. It’s more about this thought experiment of starting over from scratch. And what the reason is for why we had to start over from scratch is unknown. It’s unspecified that this is after a nuclear war or after some kind of cataclysmic climate event or pandemic or something. It’s just “hey, what if we had to” and what if we were in the woods, essentially.

Ani-Gamers: Not “what if we didn’t know that society was possible?” but that we already experienced it and had to restart.

Rohrer: That was a thought experiment I had been asking people for a number of years before I decided to make a game about this. It took us two to three thousand years, or maybe four thousand years depending on what part of the world you’re in, to get from caveman-level technology to where we are in the present day. From arrowheads to iPhones. And we kind of feel like that was primarily a knowledge acquisition problem. The reason it took so long is that we didn’t know how to make iPhones 4000 years ago and slowly over time we figured all this stuff out and now we have the knowledge of how to do this. And then I say “well, what if we were instantly teleported back into the wilderness? How long would it take to have an iPhone back in our hands if we started from scratch from rocks and sticks?

So that’s the fundamental thought experiment. And a number of people had the kneejerk reaction that we’d do it within 10 years. (laughs) And I’m like, you realize you don’t even have a screwdriver. If you want a screwdriver you’ve gotta go find some iron ore, figure out how to make steel using no equipment, and then I don’t know about the plastic handle. Good luck with that.

Ani-Gamers: This sounds kind of like teaching, even though you said you’re not trying to teach. You’re trying to get people to think through that thought experiment.

Rohrer: Well yeah. That was a fundamental premise of the game. And I think, as a provocation when I have this discussion with people, I say “I think it might actually take 2000 years again.” It wasn’t actually a knowledge acquisition problem, it was a capital problem, a foundational problem. When we go to do something today, we’re standing on the shoulders of all the stuff that’s come before and we have all these resources available to us like going down to the store and buying a screwdriver. I think we’re at the point where things have gotten so complicated that no individual living person knows how it all works. Especially for a CPU or something like that. There’s the fact that every time you click something on the Web 30 million lines of code are in between you and the data that’s coming back. Nobody understands 30 million lines of code.

Ani-Gamers: I’ve played on and off for the past two years and seen how the civilization developed, and one of the things I thought I would see was commerce. But I have yet to witness any real commerce in the game.

Rohrer: Yeah and that’s been a huge thing that I’ve been trying to get working forever.

Ani-Gamers: Why do you think it hasn’t happened? I definitely expected it, like “oh yeah, soon we’ll see people start trading.”

Rohrer: That’s been a goal of mine for the game and always been something that has never actually happened no matter what I do. What’s the fundamental reason for it? It’s an excellent question. I think it’s still a bit of a mystery even to people who have been playing the game for a long time. Everyone has their ideas. “If you just made the biomes bigger there’d be trade.”

Ani-Gamers: It’s ironic it’s the people playing the game who aren’t trading and then they’re saying “hey you need to change something so that we’ll start trading.”

Rohrer: I don’t ever want people doing things just for the sake of doing it.

Ani-Gamers: Right, just to roleplay.

Rohrer: Which is just this pretend version of it. If you chase after your child saying “be careful honey, watch out for the wolves,” and you’re just doing it because you’re pretending to be a mother and that’s what a mother would do in real life, and there’s not really any good reason to give those warnings. If there weren’t any wolves in the game but you went and told every child “be careful of the wolves in the forest honey.” That’s the worst case of it, where you’re literally pretending something that doesn’t even exist in the game, but if you have enough babies where each one stays safe but you still act like an overprotective mother anyway, just to fill your role.

That’s not that interesting to me. I’m much more interested in players behaving a certain way due to the mechanics, and the way that they end up behaving, which is the optimal way to behave, being thematically congruous. I feel like that’s the best we can do in video games, because none of it’s real, and because it’s all repeatable and you can go back through and try different ways of doing it. Even within a game like One Hour One Life where everything only happens once, there’s still the sense that you can keep experimenting in a relatively safe sandbox with different ways of doing these things. Whereas in real life you only get one shot at it.

Ani-Gamers: The stakes are higher.

Rohrer: A lot of people try to shoehorn these emotional situations into their games, mostly through cutscenes or barely interactive narrative elements. That doesn’t seem to work because players hit rewind or go back to a saved game and try the other branch. And even if there is no branching it’s even worse because as you play the game a second time you see the same canned emotion over and over again and it instantly loses its [impact].

Where I’m at as a designer right now is that the best way to achieve that kind of result is by having what I call “real play.” That is, players are trying to find the optimal way of playing the game in this situation and, in doing so, behave in a way that makes sense from an outside observer’s point of view, or thematically, or emotionally. They’re behaving the same way they would if they had that emotion. They’re kind of going through the motions for gameplay reasons but hey, what’s the difference between acting desperate and actually being desperate or acting afraid and actually being afraid?

It’s always going to be pretend afraid. There’s never a monster that’s actually going to chew you up. But if you’re playing a game where you’re supposed to be afraid of the monsters and you just brazenly walk right up to them and don’t even care, that feels like it undercuts [the emotion]. It’s these fake rubber fangs, right? You know they’re not going to hurt you. But if you dive out of the way and actually scream in real life for gameplay reasons, then I guess I feel like that’s as close as we can get to the real deal.

Ani-Gamers: Back on the subject of commerce…

Rohrer: Oh yeah so getting back to commerce, I don’t want people pretending to be engaging in trade just for fun. Some people have set up little shops and this and that. It’s like playing house. They’ll put up a little sign saying “the pie shop,” and they’ll run around the village saying “anyone want to come and taste my wares?” (laughs) But that’s just like playing house.

In terms of why people don’t: well, trade has costs associated with it. Opportunity costs and time investment and all the other kinds of things that go into it. So players need to feel like there’s a good reason, like the payoff to engaging in trade is higher than the cost to engaging in it. Even in real life, if you go all the way down to the market the benefit minus the cost for getting the tomatoes from the market has to exceed [the value of] just growing the tomatoes yourself at home.

Ani-Gamers: Maybe going down to the market isn’t even the best comparison because really there is no market at all. The question is “should we make a market or should we just share all the tomatoes?”

Rohrer: There’s a number of things. First of all there’s a big difference between your children and my children from my point of view in real life. And if we’re in a situation where there’s only one tomato, if I have my preference I’d rather have my children get it. If the situation gets tense enough and everyone’s starving to death, then people actually will engage in violence to ensure that their own children get it. In a game like One Hour One Life I don’t think that people currently have that kind of feeling, aside from [making sure they themselves can eat].

There’s also a sense that maybe there are too many resources around so there’s not enough scarcity, and there’s not a real sense of my children vs. your children. People aren’t really paying attention to whose children are whose, because there’s not really a gameplay reason to do that. I do have this “genetic score” system in there but a lot of players just ignore that. It hasn’t really had the sweeping impact where everyone is suddenly caring about their babies and so on. So people don’t really care about their own children vs. somebody else’s children, because the fundamental gameplay motivation for the next generation is just to have somebody here in the village who’s going to carry things on. It doesn’t really matter whose they are.

There’s also the fundamental problem that even if you wanted to keep some food just for your own children, there was no convenient way to prevent other people from taking it. There’s these property fences that were added a year ago, maybe a year and a half ago that are available and very easy for people to make, and very easy to control ownership and so on. But people don’t use them, because there’s still some cost to building them and people don’t feel like the cost is worth it.

Ani-Gamers: How often do you play the game yourself? How much of it is for testing? Do you ever just play it for fun to see how stuff is going?

Rohrer: There are times when I need to test a specific bug that someone’s pointed out on the live server and in those situations I usually force spawn myself in as the Jason character from the trailer and pop in with my little boonie hat and outfit and everything, and I pop in at age 42 and I can control the coordinate I pop in at, so I’ll often try to pop into some village that I’m aware of and people see me appear and “oh my god, Jason’s here!” It’s like a sighting, you know? And then they’ll talk to me or whatever. But I’m also sometimes in there testing. And I’ll say hi to people and make funny eyebrows at people or something, and then put a hat on a little baby before leaving. Or they’ll try to kill me.

Ani-Gamers: That’s funny. They’re trying to kill God.

Rohrer: Because they want the hat, right? Somebody will start targeting me and then other people jump in the posse and before I know it I’ve got three people chasing after me and I try to run away. But I also have the ability to summon any object in the game, so every once in a while if people really make me angry I’ll summon a bear.

Ani-Gamers: In the times when you’ve played a life as a regular player, are there any stories that have stuck with you?

Rohrer: I have one that I still remember from months ago. I was trying to experiment with property fences because people hadn’t been using them very much. And I was like “I’m going to create a property fence in this village for myself and my children to see how it impacts my genetic score and so on.

It doesn’t take very much to build a property fence. There’s already a village there and I went a little bit outside the village where there was some open land and started building a property fence. And when I started having babies I said “this is going to be our property. We’re going to make our own farm here.” I think we were trying to make a milkweed farm. The village was short on milkweed. I borrowed I think a hoe or something and took it in there and I think I left the gate open while using it. But someone came up and was angry that I was using the hoe in the private property. So they came and took it away and scolded me for taking it away from the town center. I said I was just borrowing it but I don’t think they believed me.

Then I took a child with me and we went out looking and exploring. We went exploring way far to the south, and we found this abandoned village that was just filled with resources. But I don’t think the people in our town knew about it. And then I started having a couple of babies down there. I explained to them, “we’re from a village to the north. It’s full of people. We found this huge treasure trove of great stuff: tools, cards, all this stuff. We should bring it back and we’ll use it to make our farm.” All my kids agreed and I nursed them and we were eating the food in this abandoned village until they got old enough to carry stuff and help.

We loaded up carts and baskets and carried them all back, and put it in our private property when we got back. But then this woman in the village came up and saw that we had all that stuff in there, this cart and all this, and she took it and stole it, and brought it back to the village center! I was like “hey wait a minute, that’s our cart!” And she was like “no, everything is shared by all.” The classic scolding me about private property thing. I was like “no you don’t understand, we didn’t take it from the village, we found it ourselves. It’s ours legitimately. We didn’t steal it.” And she said “it doesn’t matter, it belongs to the village.”

I tried to take it back in there and someone had cut a hole in my fence while I was away too, so I had to repair that. And then she got mad enough that she took out a knife and tried to chase me down and kill me. So I ran away, but I made some mistake when I was running and clicked the wrong thing and she ended up stabbing me way outside the village bounds. At that point I lost my temper and opened up the god interface and put a bear down and killed her. Which I shouldn’t have done! (laughs) Anyway, that’s the only time I’ve ever slipped up in that regard and abused my power.

Ani-Gamers: The great part about the game is that she has her own version of that story too.

Rohrer: I think if we look at that example story, it’s pretty interesting. Not that interesting to tell as a story, but as a thing to experience in a game it’s a pretty interesting story. It’s also kind of unprecedented in the realm of video games.

Most people, when they think about video games and video game storytelling, they’re thinking about these single-player experiences that are crafted by the author and maybe have some kind of branching to them or something. This was rich and complex and nuanced, and I could have maybe convinced her or been a better diplomat than I was and I learned things from it too that I could apply in future situations. Like oh, build your property a little further from town so not everyone can see it every time they walk by so people don’t feel like it’s such an affront to their village. But also in terms of the way I interacted with her or how I explained the situation. It’s like I had a bunch of different options there and it wasn’t just picking from a list. All the potential for nuance and the way things turned out and the way they spiraled out of control does feel more like something from real life or from a really well crafted movie that we could never pull off in a single-player video game just because of the fundamental nature of interactivity fighting with the non-interactive parts. In terms of potential and ways forward for video games to solve these kinds of problems in a satisfying way, I think that in a multiplayer context there’s a lot of potential there.

For the full interview audio, check out the podcast episode on the Ani-Gamers Patreon!