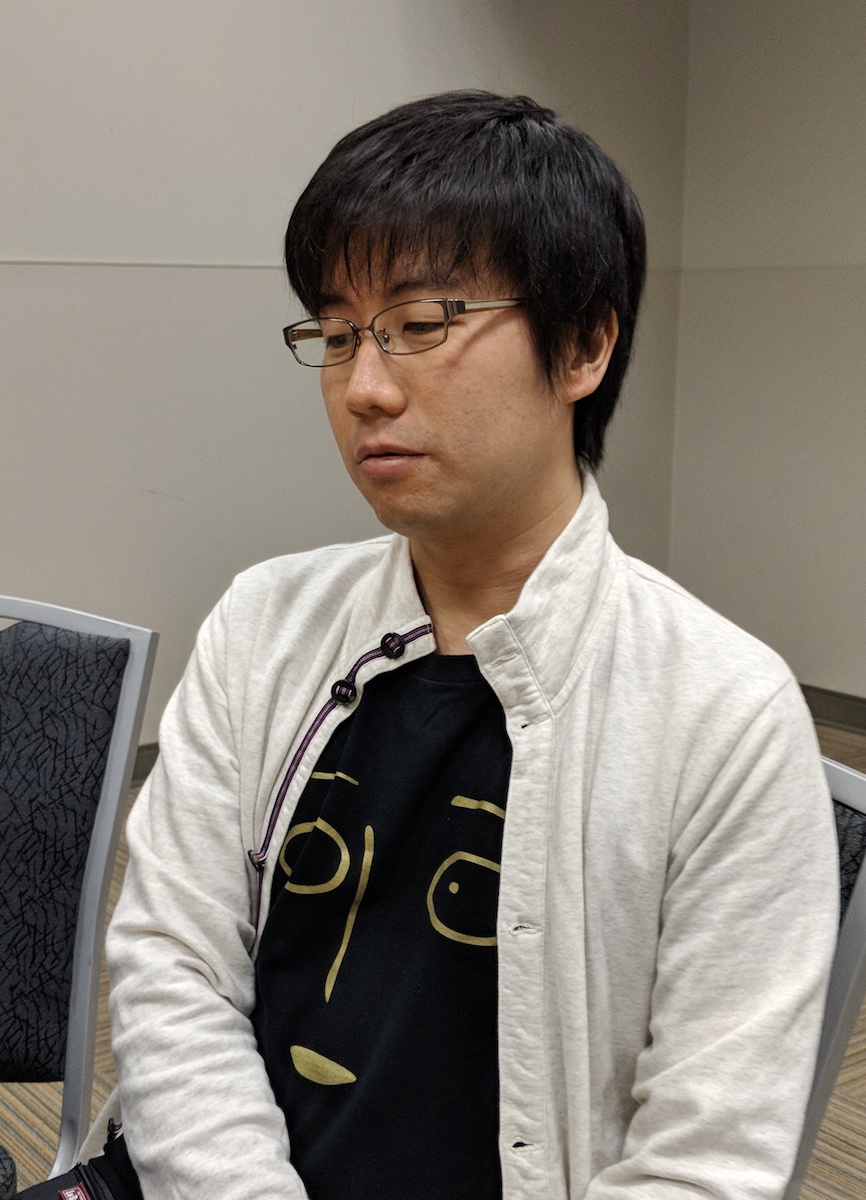

FLCL Progressive Designer Chikashi Kubota on Following in FLCL’s Footsteps

The animator and designer chats about the design process on <cite>Progressive</cite> and his love of 2-D animation at FanimeCon 2018.

As I write this, FLCL Alternative, the third season of FLCL, is finishing its run on Cartoon Network’s Toonami anime block. The two sequel series, FLCL Progressive and FLCL Alternative, have brought together teams of young animators, many of whom never worked on the original series, in an attempt by Production I.G and Adult Swim to recreate some of the charm of the original FLCL OVA.

Back in May at FanimeCon 2018 in San Jose, CA, I had the opportunity to speak with accomplished animator and character designer Chikashi Kubota (One-Punch Man, From the New World) about his work as Progressive’s character designer, as well as his approach to animation in general. In the interview, Mr. Kubota delves into the challenges of adapting and bringing his own sensibilities to FLCL’s unique visual style, and provides a glimpse into the group of young creators at the heart of FLCL Progressive. He also discusses his time at Studio Gainax, where he worked with many of the staff who created the original FLCL (though he didn’t work on the original OVA himself).

Thank you to FanimeCon’s staff, interpreter Sujay Venkat, and Mr. Kubota for the opportunity. Enjoy!

Were you a fan of FLCL before working on FLCL Progressive?

Definitely. I’m a huge fan. I consider it my bible as far as animation is concerned. Right around when FLCL was released, I started working with a company called Xebec, in my 20s. And I had such a deep respect for all the artists working on it, such as Hiroyuki Imaishi, Sushio, and Yoh Yoshinari. It just felt so larger-than-life to me, to see this project completed with all of their names on it. That had a huge impact on me. At the time I definitely did not think that I would be working on the character designs for another FLCL project, but to be able to follow in their footsteps has had a great impact on me.

How closely have the original staff been working on the project? Have you had meetings with any of them? I know Mr. Tsurumaki has been involved.

It’s actually mostly new staff. Mr. Tsurumaki gave us some references as far as the world-building and the setting, so he’s definitely a great resource on that end. But other than that, I can’t really think of other staff members from the original series that have been too involved with the series. As a result we really hope that, despite mostly being new staff, we can convey the same feeling, and there’s a little bit of the Gainax spirit that remains in the series.

I heard that Mr. Sadamoto provided some original designs.

Yes, he did as well. I’m very glad that he was able to participate.

What was that process like with him?

For the new series there are six characters including Haruko that were originally designed by Mr. Sadamoto, so other than that, everything else was designed by me. But how that came about is a little bit complicated.

Of course the characters in the original series were designed by Mr. Sadamoto, but if you remember, there was a huge influence from Tadashi Hiramatsu’s visual style, so it was a combination of the two of them. Mr. Hiramatsu’s visual presence was too strong and almost overwhelmed the actual character designs themselves.

Basically, the creation process for Progressive was that I got an offer to work on it while I was at Gainax, and at the time that I was sort of following in Mr. Sadamoto’s footsteps. He was my senpai. I was sort of being mentored by Mr. Sadamoto, and I got taught by Mr. Hiramatsu as well. So in a sense I drew inspiration from both of them.

But my main point is that Mr. Hiramatsu’s visual presence no longer had as much of an impact. The new style that I was going for was more of a combination in which I took inspiration from both of them. To put it simply, maybe FLCL fans around the world think of FLCL as looking like Mr. Hiramatsu’s designs from the original. But for me, I wanted to match both almost equally, which means having more of Mr. Sadamoto’s influence than the original. So it might not live up to fans’ expectations. I’m certainly hoping it does though.

Every episode of FLCL Progressive has a different director, and in the original FLCL those episode directors took a lot of creative liberties. Do the episode directors for Progressive have more control over each episode than on a typical show that you work on?

Of course, as you said, there are six different directors, one for each episode. But actually the main one that’s overseeing each one is Episode 1’s director, Kazuto Arai. He’s in charge of the scenario and series composition and he oversees the general flow of the series. Despite there being different directors, he’s involved in the entire process. He’s 27 years old, but despite being so young he has a lot of talent. You can probably find his work on Twitter @Barikios. But yes, that is sort of how the organizational structure is working this time.

What is your animation process? Do you use references? Do you act things out?

When I’m working as an animator, the core part of my job is to look at the storyboard and make a scene out of 20 to 40 “cuts” from the storyboard. So basically I start with a single image while comparing that to the storyboard, and then looking through the scene itself, I imagine every frame and the entire fluid process in my head. So I start from that one image, and then I have to imagine every step. Then, going through those steps in my head, I’m able to draw it out and bring that to life.

So you do it in your head? You don’t use a lot of references?

It’s definitely on a case-by-case basis. As far as the general process, I’m usually only given one reference image or sometimes even just a setting or the background. If it’s for a more passive scene then maybe I’ll be able to reference the background or the imagery around it and then create the scene. But for action scenes I do most of it in my head. Sometimes I’ll maybe watch an action video or something as a reference. But most of the actual execution takes place in my head.

Of course there are a lot of new processes in the animation industry. So, for example, with 3DCG, they use perspective to emulate a zoom out effect, using a box and then moving that entire framework along with the character. I’m able to use that as a reference point. And also I do a lot of experimentation to replicate effects like smoke or explosions.

One of my goals in the animation process is to make sure I highlight how wonderful hand-drawn animation is and make sure to distinguish it from other mediums such as 3DCG. When you have a 3-D model, when you use that as a reference and take it all the way, sometimes there’s a little bit too much reality infused into it. It becomes too different from the hand-drawn process. So I like to maybe use it as a reference but not completely recreate that 3-D effect. I want to make sure that there’s still a clear delineation, a clear divide that shows that this is a hand-drawn, 2-D animation. I feel like there’s also more artistic liberty when it comes to 2-D animation. I’m able to avoid falling into that trap of realism, and as a result I’m able to show my artistic side.

For me the most important thing is definitely visualizing the scene in my head. If I’m looking at a reference picture first, then I become too caught up on making sure that I match that reference. And it becomes an entity that’s different from what I might have imagined if I started from scratch.

You mentioned you experiment a lot with effects animation like explosions and smoke. I’ve definitely noticed a lot of really interesting effects in your animation. What’s that experimentation process like for you?

It’s definitely a complicated process, but just to give you a breakdown, I use real effects such as those in actual movies and other things as a reference, plus I use really good animators who have done similar scenes. I watch their scenes if they have a particular way of doing it or I may even a particular frame in mind that I can reference as for how I want to start the process. And of course the most important is visualizing in my head. The combination of these three elements is how I begin to create the effect. Of course the biggest hurdle is, unless you have quite a big budget, you can’t actually recreate the effect yourself with things like smoke and explosions. So using these reference points is very important.

While I’m drawing it I have a lot of fun. For example I start with the base scene and if it’s an explosion slowly increase it in size, maybe add a few more details, and if there’s other debris or collateral that gets caught up in the explosion I start to insert them here or there. And if there’s a mistake and the entire scene becomes different from how I imagined, I can easily go back to the point where it changed and make a slight change there. So it’s actually a really fun process even though it takes quite a bit of time.

Do you do that digitally?

It turns out that right before coming to FanimeCon I actually did a scene with an explosion, and while I started out doing it digitally, I kind of got caught up in it and I really couldn’t get it the way I wanted to, so of course in the end I had to do it all on paper.

The two pieces of software I use are Flash and Clip Studio Paint, and sometimes I alternate between the two if I’m doing digital. This time I decided to start with Flash, and during the process I realized that a lot of the younger animators who started in their 20s, they’ve maybe started their animation career working with digital for everything, so they might be used to the feeling of it, and get into their groove with digital. But of course for me, I started with paper, and one of the most significant highlights of paper for me is that I can actually feel the coolness and the spectacular effects that I draw just pop out at me. It’s just a sort of feeling. By touching the paper, it gives me a personal touch. I can’t exactly put my finger on what it is, and of course everyone is different. Each animator has their own style. But for me, when I put the form to the paper, that’s when the scene itself comes to life.