“Cassette Girl,” 3-D Animation, and Beta Tapes with Hiroyasu Kobayashi and Shigeto Koyama

The director and designer of the <cite>Animator Expo</cite> short discuss the production process and their artistic influences.

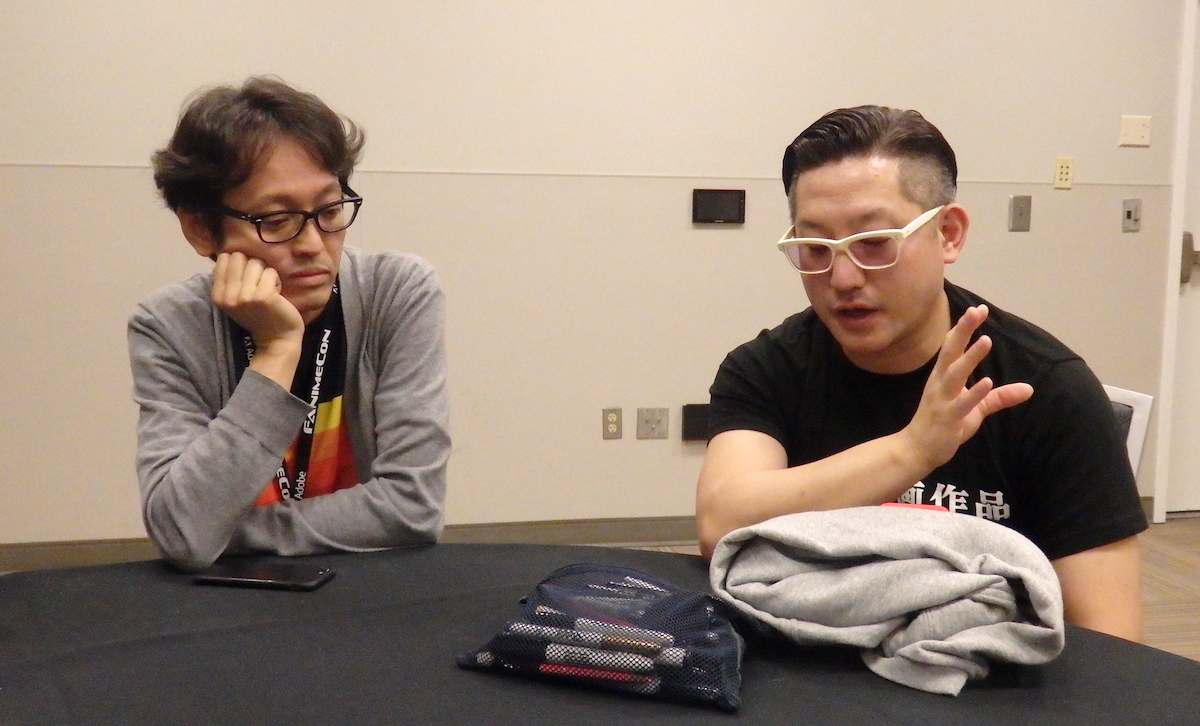

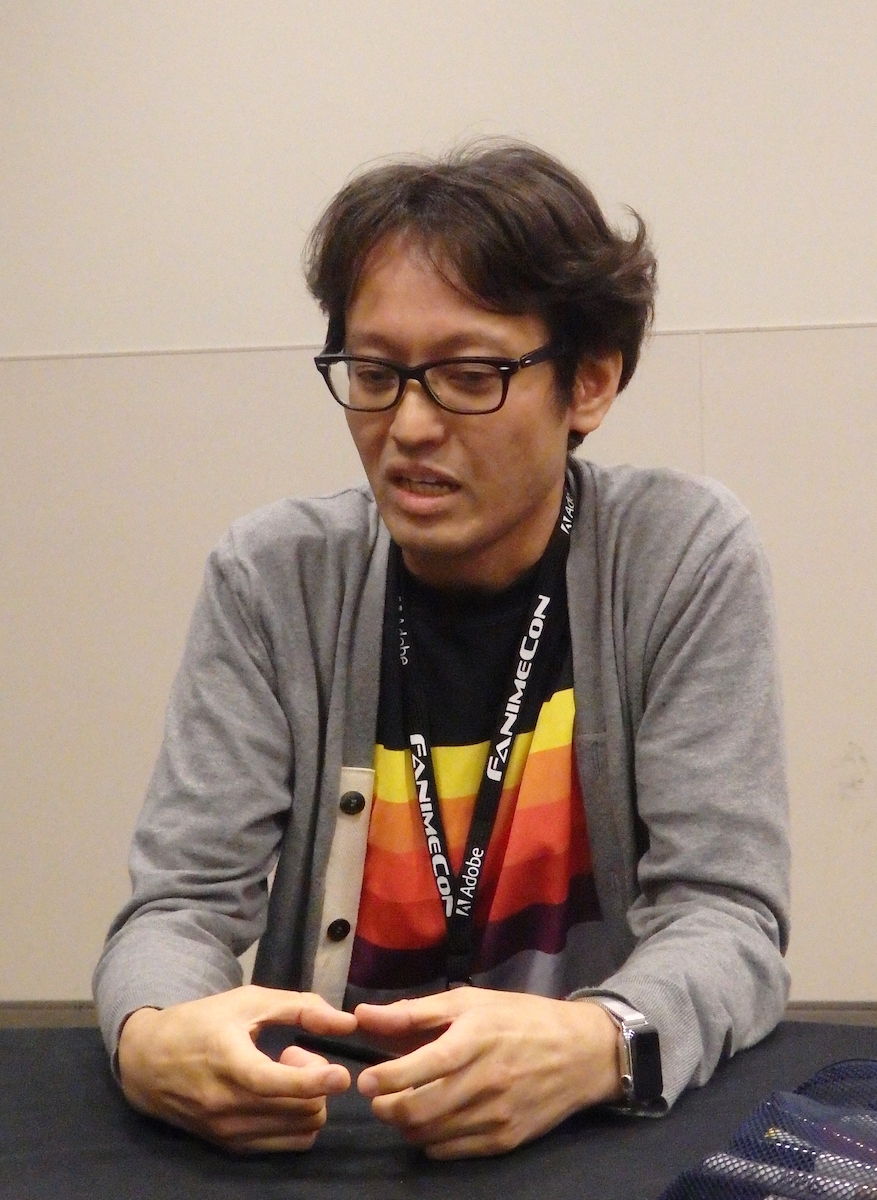

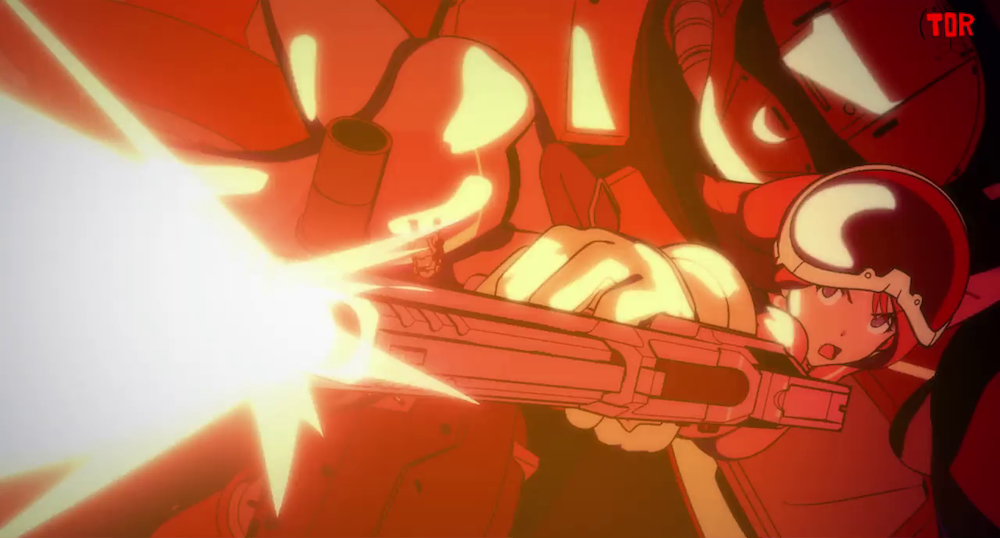

Studio Khara’s Animator Expo series of shorts is chock full of brilliant ideas and incredible animation, and one of my personal favorites, Cassette Girl, is produced by Khara’s in-house CG animation team. The short garnered attention thanks to its retro obsession with beta tapes and its homage to the “Daicon animations” — convention opening animations produced by Khara founder Hideaki Anno & co. before they created the now-famous Studio Gainax (Evangelion, FLCL, Gurren Lagann). But it’s also part of a growing list of Japanese computer animation that’s challenging the traditional divide between 2-D and 3-D art in the anime industry. Cassette Girl uses computer animation tools to achieve ambitious acrobatics and camera movements while retaining the punchiness and stylization of traditional, hand-drawn anime. That’s in large part thanks to the design and directing work of Shigeto Koyama (Heroman, Inferno Cop) and Hiroyasu Kobayashi (Gravity Rush: The Animation – Overture), respectively. I got a chance to chat with both of these artists in an extended interview at FanimeCon 2017, in which I picked their brains on the production process behind Cassette Girl, their influences, and the future of CG animation in Japan.

Thank you, Mr. Kobayashi, Mr. Koyama, interpreter Ms. Satsuki Yamashita, and FanimeCon’s staff, for making the interview happen. Enjoy!

Let’s begin with a simple one. How did Cassette Girl get started?

Kobayashi: When Studio Khara decided to make Animator Expo, since the studio has different departments they wanted to have the digital department — which is the department I’m in — do one too. Everyone turned in proposals and mine was chosen. But eventually they decided to do more shorts so the other proposals, like “Hill Climb Girl” and “Rapid Rouge,” were also made. Mine was chosen first, but in the end, because I was helping with the other ones, it was finished last.

“Cassette Girl” is obviously really inspired by the Daicon animations. What was your relationship with those animations before you made it?

Kobayashi: We were just fans.

How did you first watch them?

Koyama: Since there was no YouTube at the time, the way young people traded video is they had copies of video tapes that they passed around.

Kobayashi: It’s similar to how porn is passed around.

There are some old-school Gainax staff members like Anno at Khara. So what did they think about the project?

Kobayashi: Anno hasn’t said anything. We haven’t discussed it. There’s probably no one who worked on Daicon at Khara anymore other than Anno and maybe Mahiro Maeda. Maeda probably worked on Daicon. He’s a good guy so he always says “good job.” Anno and I are both shy so we don’t really talk about those sorts of things. I think he does understand that it was made out of respect, as an homage, but because both of us are shy, I’m not like “did you get it?”

Is there a copy of Cassette Girl on beta tape?

Kobayashi: No, there isn’t. Even if we made one, how is anyone going to play it? I did make those labels that you can put on beta tapes.

Do you sell those?

Kobayashi: No, they’re only for staff.

Showing What 3-D Can Do

One of the really interesting aspects of “Cassette Girl” is that it’s in 3-D. Is there any particular reason why you thought 3-D was a good fit?

Kobayashi: Without 3-D, anime is getting hard to produce because there’s no manpower. But I wanted to make something that 2-D anime can do. I wanted to showcase what 3-D can do without making it look like a Final Fantasy movie. I really put everything into it to make it as good-looking as possible.

I think CG anime is still a little bit new. Not many people know about it, so … well, I wouldn’t go as far as to say it’s to “educate” people. But I wanted to let people know what it can do. When people wonder, “what can you do using 3-D anime?” this is the answer.

That’s something a lot of fans have picked up on. It’s a 3-D anime that feels in a lot of ways — a lot of good ways — the way 2-D anime feels. From a technical perspective, what sorts of things did you do to try to achieve that effect and make it closer to 2-D anime?

Kobayashi: During the rendering and compositing phases I used a lot of masking to make the shadows.

How is that different from what previous 3-D CG anime has done?

Kobayashi: The difference is that other 3-D anime won’t use a lot of the masking that we did, because it takes a lot of time. What helps to make something look as hand-drawn as possible is controlling a lot of the shadows. So you’ll notice all the CG anime that don’t look real don’t have a lot of shadows. In hand-drawn animation, since you’re drawing everything, by using shadows you create the effect of it looking more real. So we took a lot of time in doing that.

So other CG productions either have fewer shadows or they rely on automatic shadows? It sounds like you’re doing more manual control of the shadows.

Kobayashi: Yeah.

Were there any differences in how you rendered the lines?

Kobayashi: Not really, we didn’t do anything special.

Was the goal of showcasing what 3-D CG could do part of the character design as well?

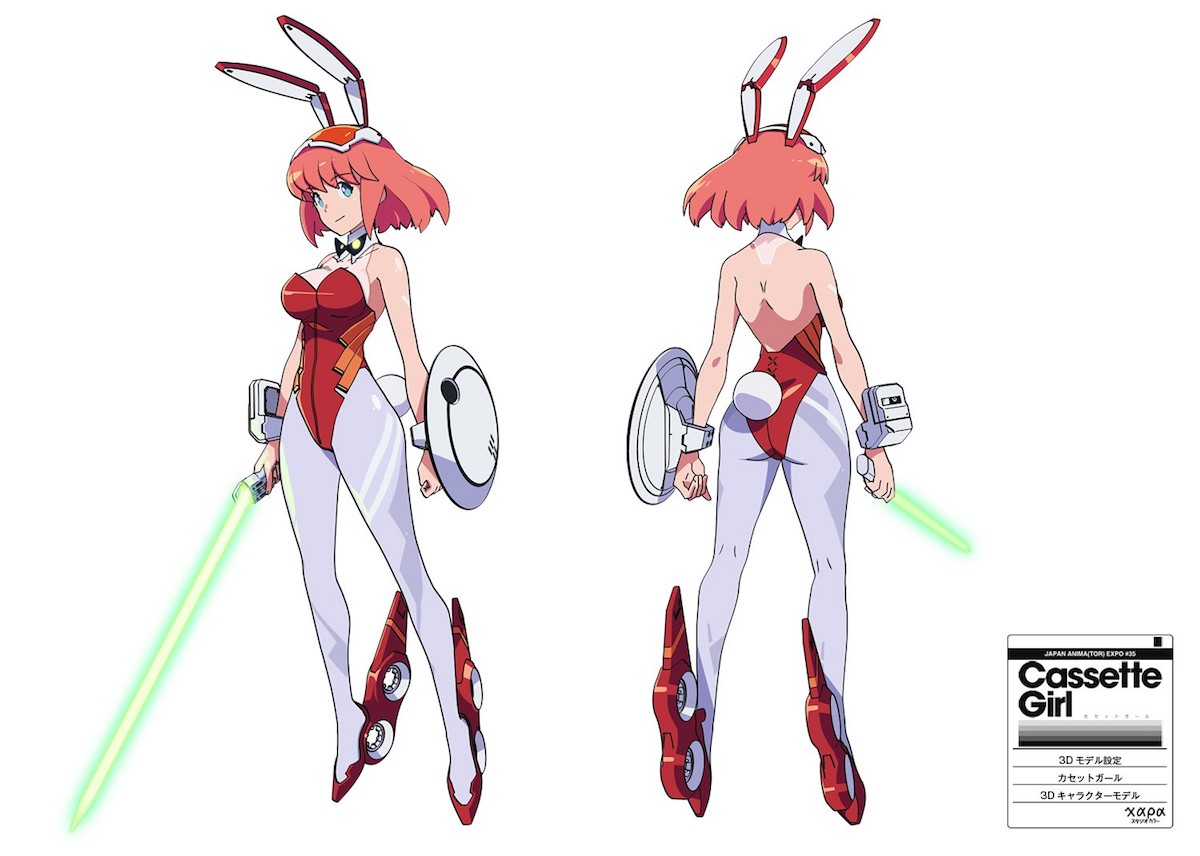

Koyama: The advantage of doing character design for 3-D anime is that you can start with the 3-D modeling. So all the details can already be in the model. This happens with other CG anime and even video games. But even if you put details into the character design, it gets crushed when it gets rendered into a 2-D image. For Cassette Girl, what I did differently was I made the thighs look like they were painted … sort of like body paint. So when she moves that painted part follows.

So it reinforces the shape as it moves?

Koyama: Yeah. Normally a designer for video games would tend to add more textures or more thickness to describe the shape, but I used that body paint style instead. It was a combination of the techniques you use in hand-drawing and the techniques you use in modeling.

Translator: Did it help that you also designed for video games and anime, so you were able to combine the two?

Koyama: It’s more like it was an anti-video game design way of approaching it. I prefer the simple way of designing for anime but I wanted to make it highly detailed, so I think that helped.

Kobayashi: In video games the details are more important, the details of the textures or on the face, but in anime it’s more the form. The form is more important, not the texture.

Why do you think that is?

Kobayashi: I guess in animation the way it moves is more important than how it looks.

A lot of CG productions use a limited frame rate in order to match hand-drawn animation. Is that something you played around with at all on Cassette Girl?

Kobayashi: Frame rates are something that animators decide. It depends on how they want to show it. Sometimes it’s eight, sometimes it’s 12, sometimes it’s even 24. So on Cassette Girl it wasn’t decided. In normal animation you usually don’t set these rules because it really depends on the animator and what he wants to do with that sequence. So the only times that we would say “it’s gonna be this frame rate per second” is when it’s a huge production and the animators are inexperienced so they don’t know how many frames to do. So we would set those, like “this anime is all gonna be 12,” “this anime is all gonna be eight.” But like other normal anime, Cassette Girl didn’t have those rules.

So you used framerate modulation? EDITOR’S NOTE — This is a technique for varying the framerate popularized by Toei/Ghibli’s Yasuo Otsuka.

Kobayashi: Animators tend to just research other people’s works, so they’ll watch it frame by frame and go “oh it was two here but then when it gets into action it’s one.” I think everyone tends to research and that’s how they get the experience and understand what looks good and what doesn’t look good. So I think they might say ”this action is really good,” watch it frame-by-frame, and figure it out like, “OK from here to here it’s three, and then from here to here it’s two.”

EDITOR’S NOTE — Here Kobayashi is referring to “ones,” “twos,” and “threes,” animator jargon for “24 frames per second,” “12 frames per second,” and “eight frames per second.”

The good thing about CG is there’s no in-betweens. So in normal animation you have key animation, key animation, and then the in-betweener has to figure out how many frames they have to fill in. And the producer has to think about the budget. But that’s not necessary in CG. So to make it easier, you just make it automatic. You let the computer generate the in-betweens. Then the animators who have experience, who know what will look better, can tweak it.

What do you think the future looks like for 3-D CG?

Koyama: I use 2-D and 3-D and I don’t draw by pencil much anymore, but there are people who still use both. If they draw, they’ll scan it in and do stuff on Photoshop digitally. Then there are people who just draw and use Copic markers to color it. I think it depends on the person. I don’t think it’s just going to be 3-D CG, and I don’t think it’s going to be the savior of anime.

I grew up with 2-D animation, so of course I have some attachment to it. But there are bad anime drawn in 2-D. And then there are also bad anime done in 3-D. So it really just depends. If everyone can make the best anime that they can with whatever method they choose, that would be for the best. There are good ways to design for 3-D, and then there are good ways to design for 2-D. But neither is actually the correct answer. In the end, both are important. It’s not really a matter of technical things, since 2-D design and 3-D design are both technically different. It’s about how you can make the best design using whichever way you choose.

In the end, you just have to think about whether 2-D or 3-D or both is appropriate for a design, or else it’s not going to matter; you’re just going to get shitty stuff. It’s not like you have to use 2-D or 3-D to design. It’s just about picking whichever is the best way to make what’s most interesting and what looks good. For example, Inferno Cop doesn’t have to move, so that’s why I made him that way.

Kobayashi: I also don’t think CG is going to save the anime world or anything, but since I do work on CG, I think about what one can do with it. Cassette Girl ended up having a 2-D feel, because we felt like it was the best way to showcase what 3-D could do. But who knows? If we were to make a sequel or a series, it might not even look like that. It might look like Pixar. It depends on what would make the story more interesting. So I guess we have the same sort of answer.

Personally I’d love to see more anime exploring 3-D CG that doesn’t try to look like 2-D anime.

Koyama: Are you saying there are too many 3-D CG anime that look like 2-D?

No, no. I think Japanese animators have a really unique and interesting perspective on animation, and it would be really interesting to see what kinds of cool things they do with 3-D when not trying to imitate 2-D.

Kobayashi: I agree. Among the creators, there aren’t many people who think that. Even if they want to create something 3-D, they have so much respect and admiration for the Pixar movies, they might just look like copies. What they see in Pixar movies might be too strong for them. It’s hard for them to break out of their shell.

Toys & Idols

What sort of things inspire your work? Are you a big fan of other anime work, TV, music, or something else?

Koyama: I’m not as into that many American comics and toys as before. Since the last time I came to Fanime a few years ago, I’m not buying things as much. Hm … maybe cars. Last year I bought a car, which felt like buying the ultimate, biggest toy.

What kind of car?

Koyama: An Audi.

Currently I don’t have a hobby. It’s sort of cars and food. Around Kill la Kill, before and after it came out, toys are really what drove me to design, but I’m so busy churning out designs it feels like I’m not really taking in much right now. I guess old manga? Showa-era manga like Glass Mask. A bunch of creators, like Anno, read shojo manga.

Kobayashi: It’s so vastly different from shonen manga. At first I didn’t even know how to read it because the panel layout is so different!

Koyama: Imaishi too. He was originally a manga artist, under a pen name.

Kobayashi: I like idols. I never got into AKB48, but I like Nogizaka46 and Keyakizaka46.

Translator: You like Perfume too!

Kobayashi: Perfume is the sort of idol where it’s OK to say that you like them. It’s very similar to how I said in my panel that Evangelion is OK to like. It’s not creepy to say you like Perfume because you feel like you like them more because of how they do their stages or because of how each of the girls plays her character. I feel like with Perfume, the sound and the staging design is all done by a designer, so in that sense their concerts or performances feel like an anime too. But enough about Perfume! In terms of other things … well, there’s a cycle.

Translator: You still bought Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle toys.

Kobayashi: It’s different. Liking something for a long time versus having something being the motivation to create. And it’s more in a cycle. I’m having a hard time answering.

Koyama: It’s not like I don’t like American comics anymore. I still like them. I guess it’s not in a good situation in Japan right now. The American comic scene isn’t good in Japan.

Kobayashi: With idols, I do feel like it’s just a hobby to collect idol stuff, but when you look at their performances or their music videos, it is a way of creating art. So there’s a lot to learn.

Music has always influenced me, but I’ve been mostly interested in ‘90s American and British music lately. It was a good time. They Might Be Giants, The Spice Girls. Indie pop was really good in the ‘90s.

Check out more coverage of FanimeCon 2017, including my interview with Hiroyuki Yamaga, one of the Gainax founders who worked on the original Daicon animations!