“You Are Our Future”

The multi-generational MMO <cite>One Hour One Life</cite> is a beautiful, heart-wrenching experiment in collaborative gameplay.

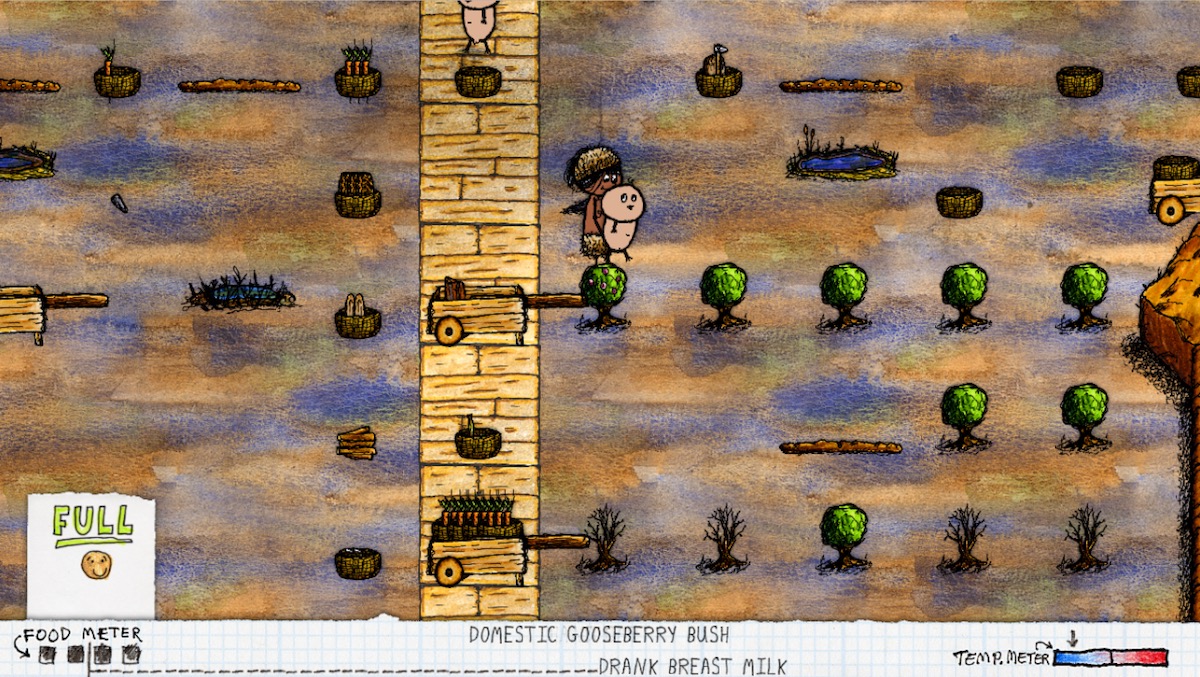

I’ve been playing a lot of Jason Rohrer’s new game, One Hour One Life, lately. It’s a fascinating concept — part MMO and part social experiment. Essentially, it’s a multiplayer survival game in a persistent world in which players craft tools and attempt to sustainably manage resources like food and water. The title alludes to one of the game’s more innovative concepts: players age one year every minute, and die when they hit age 60. On top of that, new players spawn as the children of other players, and they’ll starve unless cared for by the adults. It’s the survival and crafting mechanics of games like Minecraft but spread across a multi-generational playerbase. Implicit in the game’s design is a question: will the community self-organize into a productive society, or devolve into chaos?

Rohrer (The Castle Doctrine, Diamond Trust of London, Sleep Is Death) is no stranger to games that question our assumptions about play, and One Hour One Life takes aim in particular at something that goes unquestioned in many games: the notion of player individuality. The almighty Player is frequently the center of the universe, especially in competitive or single-player games. But other genres exhibit the symptoms too. Team-based games like Overwatch reward players with items and achievements, making the team’s progress a mere stepping stone toward individual goals. Even nonviolent sims like Animal Crossing are guilty of it. Players spend their time accumulating items and money and shaping their town as they see fit with the implicit reward of surveying their kingdom when they’re done.

There’s nothing wrong with this per se (though I could write a whole article about its implications for griefing and trolling), but once you see it everywhere, it starts to seem like a limitation. History shows countless examples of societies and political movements with collective models, whether it’s labor unions, subsistence farmers, or kibbutzim in Israel. Why can’t games give us experiences that mirror the real-life experience of collective struggle and collective triumph? It’s a hard habit to break, especially because so much of human nature seems rooted in individual risk-reward analysis, but One Hour One Life actually pulls it off.

Paying It Forward

One of the most shocking things about One Hour One Life has been watching players selflessly help each other through problems. Newborn players are almost entirely helpless, unable to pick up items, feed themselves, or even communicate! The only way they can survive is by women (“Eves,” as the game calls them) using up their own precious food meters to breastfeed them for around three minutes. At first, this seemed impossible. What online gamer would risk their own resources to help another player without a clear reward? Think about games with moral choices like Bioshock, where so often designers have to make the “good” choice more rewarding than the bad one in order to encourage positive behavior.

But players did it, and not just a tiny minority of them. I was born to mothers who scrambled around picking berries to keep us both alive, only to die soon after I came of age. One mother taught me how to plant carrots and start a farm, supplementing the game’s intentionally minimal crafting UI (there’s no tutorial, naturally). Maybe she learned how to farm herself through trial and error, or maybe she learned it from her mother. I never got a chance to ask her, but soon enough I passed the knowledge along to my own child. More cynical players might call this an inefficient game of telephone in need of a UI revamp. I call it an oral history.

Why did they do this? Look no further than the universality of the game’s generational mechanic. Every player is the child of another player (more or less, though players may spawn as adult Eves if there are no childbearing Eves left on the server). If you’ve been cared for by another player, it’s hard to neglect the next person who comes along. It would be one thing if they were an NPC — we can very easily detach our moral compass when it comes to fictional characters — but these are fellow players in need of help. When you needed help, someone gave it to you, so it’s at best rude, and at worst cruel, to not extend that help to someone else.

That’s not to say One Hour One Life is a cooperative wonderland, but even its cruelest moments are social events with fascinating moral implications. Early on I joined a village and started having children, but the other adults told me to “let them die.” We didn’t have enough food to feed ourselves and the children, they said, so bringing them into the world would be a waste of time. I balked, and refused to let the children die. Soon enough, I ran out of food and died along with my children; in retrospect it would have been kinder to simply leave those players to starve.

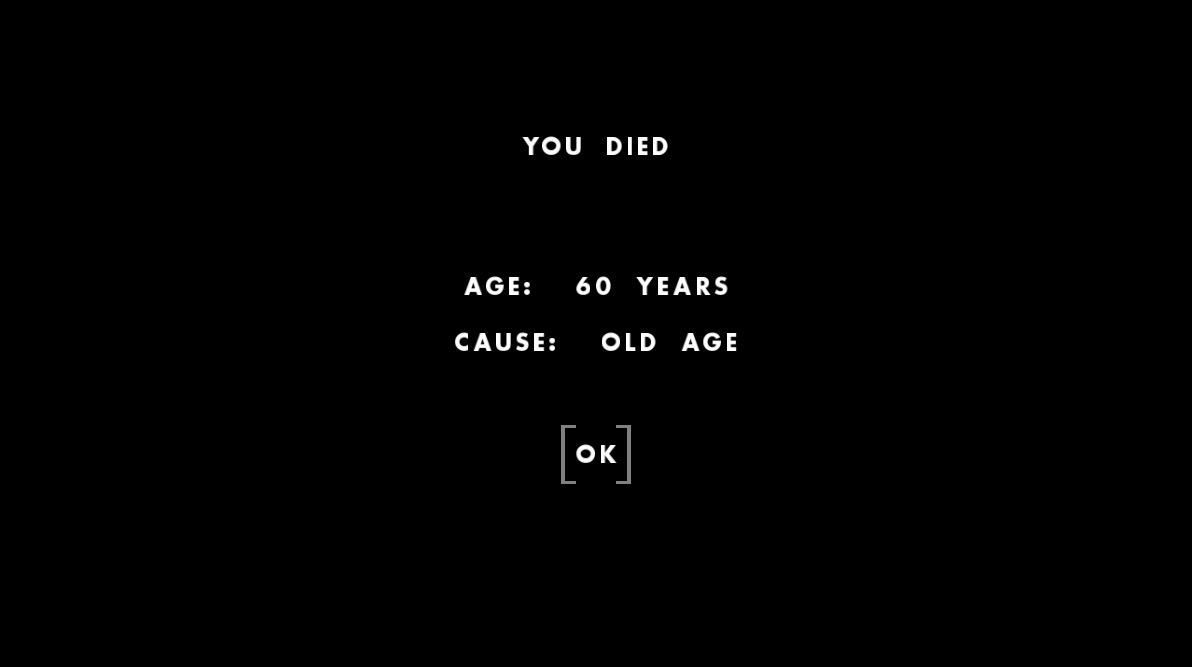

Embracing Death

The permadeath mechanic is also a big part of the game’s cooperative nature. There’s no shared progress across lives, no leaderboard or achievement system. The screen simply goes black and you’re kicked back to the start screen to try again, with no knowledge of how your children are doing now that you’re gone. Other games make everything about the player, but One Hour One Life strips away that self-importance.

Since each game lasts only an hour at most and players can’t carry over any achievements, there’s no real incentive to pursue selfish goals. Death takes us all in the end, and when it does, everything we do will effectively be wiped away. So almost all the players I’ve encountered have found a different purpose: collective achievement!

Building Together

Without selfish goals to pursue, the only thing left is to help others. You might not be able to do great things in an hour, but you can raise a family or create a foundation for others to build on. 60 minutes later, you can look back on your small seed and trust that it will grow into something much bigger.

The individual struggle, then, is to find some satisfying way to contribute. Many players end up specializing in a skill, whether it’s rearing children, making clothing, or harvesting carrots. If a village has enough people working together on these tasks, it can last for dozens of generations (the current record for longest generational line is 31 players long!).

The game has PvP, so naturally there are griefers, but even that classic video game problem has a collective solution; villages have started assigning people as guards to kill griefers, creating an entirely new power dynamic centered around violence and law enforcement. And with the permadeath and aging, griefers might think twice about attacking a guarded village — after all, they’ll have to go through their childhood years all over again before they can continue their rampage.

When all of these social dynamics and game mechanics come together, One Hour One Life provides an experience unlike any other game. It takes advantage of basic human social dynamics, our tendency to want to help and be helped by others, and convinces players to work for the greater good. Rarely has a game given me the sense of pride I got from rearing two children who grew up to be successful farmers, or the sense of gratitude that I felt when my brother fed me after our mother abandoned us.

One Hour One Life is full of stories like these, but the one that had the biggest impact on me was the first time I lived to age 60. I was a member of a large, successful village, raised alongside a half dozen other children in a small nursery. When I came of age I became a carrot farmer, eventually taking over the farm into my old age. But eventually we realized there were no more childbearing women left in the village, meaning we wouldn’t spawn any new children. Our once thriving village was about to die. Now the elder of the village, I made the decision to bulk up our carrot and clothing stockpiles so we could at least leave something for passers-by and die with dignity. But then, as I reached 59 years old, a woman and her daughter appeared from the wild, looking for food and shelter. I rushed over to them, the whole village there to welcome them. In my final few seconds, all I had time to say was “you are our future.”