Chiyoko Fujiwara Has Come Unstuck in Time

Reveling in the fractured, nonlinear surrealism of Satoshi Kon’s <cite>Millennium Actress</cite>.

This week I had the pleasure of seeing the late Satoshi Kon’s Millennium Actress in the theater. It’s not just my favorite anime movie but my favorite film of all time, so I’m ecstatic to see that the anime market in the US has grown so much that we can get widespread screenings of Kon’s films, including this one and Perfect Blue. With Millennium Actress fresh on my mind, it seems to me like a perfect time to once again sing the praises of this sublime, quietly breathtaking film.

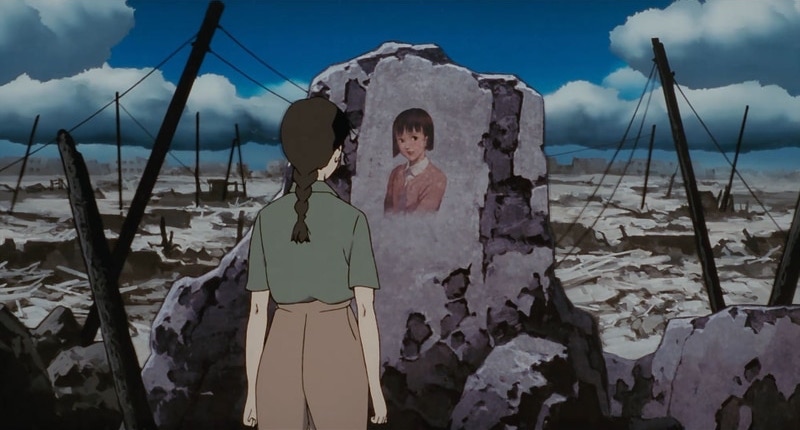

Lots of films and TV shows follow multiple timelines. There’s the ping-ponging intrigue of Memento, the flash-back-and-forward structure of True Detective and Lost, and the Guy Ritchie-inspired anime series Baccano! But Millennium Actress’s multiple timelines are a completely different breed. The film isn’t a puzzle box to be deciphered, with all its loose ends linked up with their corresponding pieces. It’s a hall of mirrors to be explored, with images bent and reflected endlessly into the distance. Millennium Actress depicts three timelines of vastly different scale and scope, interleaved into one another: the life of its titular heroine Chiyoko, the history of Japanese filmmaking, and the history of Japan itself.

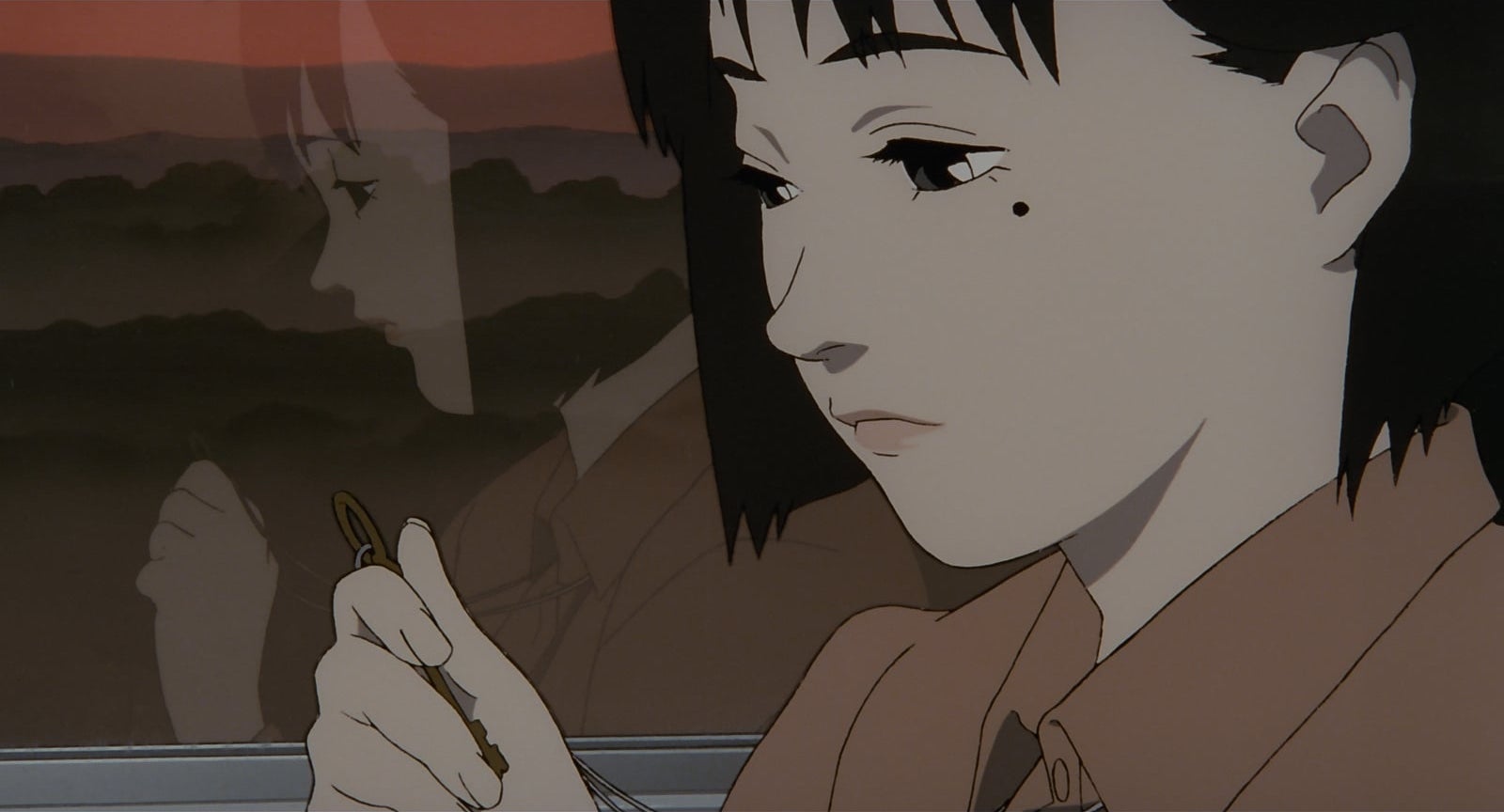

Chiyoko’s timeline plays back relatively consistently, moving forward in time as we watch her age from a newborn to an elderly woman, always searching for the man who gave her a mysterious key one snowy day. Her journey through the world of Japanese film follows a similarly linear progression. It’s when Kon throws the history of Japan into the mix that time begins to distort. Movies can transport you to any place and time, and Chiyoko’s films, by bouncing back and forth between medieval period pieces, modern dramas, and science fiction set in the far-flung future, do just that. The history isn’t just covered by the movies themselves either, but also by Chiyoko’s lived experience, which covers the turbulent history of 20th century Japan. Chiyoko simultaneously exists in all of these time periods at once, immortalized on screen. It’s in this sense that she is a “millennium” actress — trapped in a thousand years of solitude, cursed to replay her tragic love story for all time.

In short, Chiyoko has come “unstuck in time,” the condition described by Kurt Vonnegut in Slaughterhouse Five in which his protagonist Billy Pilgrim experiences moments from the past, present, and future seemingly at random. The allusion wouldn’t have been lost on Satoshi Kon, who repeatedly professed his love for George Roy Hill’s Slaughterhouse Five film adaptation. That single film had an immense influence on all of Kon’s work — Hill’s heavy use of match cuts in particular.

Match cuts, in which one scene transitions to another using one or multiple shared elements, were a favorite of Kon’s across his entire career, and Millennium Actress is a masterclass in the device. Earthquakes, a frequent subject of the cuts, jolt characters out of reverie and back to reality while connecting with Chiyoko’s statement early in the film that her life is tied to earthquakes. Doors also feature heavily, helping to carry the audience between major scene changes, as when the door of a derailed train suddenly leads to a feudal battlefield.

Most important of all, however, is the climactic scene with Chiyoko running to meet the man she’s been chasing after. The entire film is structured around this moment, with seemingly one-off shots — Chiyoko slipping and falling in the snow, her friends laughing about her first love — blending together into a single continuous scene. Though each of these shots is separated by decades of her life, they form a unified whole. We see Chiyoko’s entire life at once, in flattened, non-linear time.

There‘s a temptation, especially among American moviegoers, to explain all of this, to come up with a rational scientific reason for it. “It’s Chiyoko’s memories,” “it’s her mind playing tricks on her,” things like that. This does a disservice to what Kon is trying to achieve. Nearly every scene in Chiyoko’s past is patently impossible, even if you ignore the presence of documentary filmmaker Genya and his cameraman in the flashbacks. She has conversations about her personal life while in character for a film, making specific references to her cherished key and the man she’s after that are obviously not intended to be literal parts of her movie scripts.

In one scene, she’s cleaning her home and finds where her husband hid the key, only for Kon to zoom out and show the entire domestic scene as merely a set, with no camera crew in sight. Are we to believe that the key was hidden inside the set and Chiyoko was cleaning this fake home like a dutiful housewife when she found it? Of course not. What we’re seeing is a bit of reality and a bit of fantasy, placed in a box together and shaken up. Re-separating the parts and labeling them as “fact” or “fiction” is meaningless and detracts from Kon’s message.

That message is one that should connect with anyone who has ever fallen deeply in love with a great story. It’s the conviction that stories are what keep us going, whether they are real or fake or some unknowable mix of the two. And it’s a quintessentially Satoshi Kon insight that when we tell ourselves the stories of our own lives, we are always creating a fiction – inspired by reality but tweaked ever so slightly to grant us that much more clarity and purpose.

Millennium Actress is in theaters in the US for a limited time thanks to Eleven Arts and Fathom Events. Tickets for the Monday, August 19 screening, featuring a brand new English dub, are still available.