Secret Santa Review: Death Parade

Everybody, put your hands up.

Welcome to Anime Secret Santa, a gift exchange run by our friends at Reverse Thieves where the gifts are anime review recommendations.

This year my Anime Secret Santa choices were pretty easy: a sci-fi sitcom (The Disastrous Life of Saiki K.), a back-to-high-school adult drama (ReLIFE), and a morbid rumination on the afterlife (Death Parade). You know I had to pick the one with “death” in the title.

Decim is the stoic, silver-haired bartender at the cocktail bar Quindecim, where he spends each episode serving a pair of guests drinks and challenging them to games like darts and bowling. But Decim is no ordinary bartender: he’s an arbiter of souls, and his guests are the recently deceased. Through observing them as they play the games, he determines whether to send each one to heaven or hell.

Death Parade continues a long tradition of anime series where an impartial hero drifts through the lives of others, helping them or judging them or possibly even killing them. Like the legendary assassin Golgo 13, Decim’s unsmiling facial expression remains fixed in place for most of the series, and his hairstyle will remind Mushishi fans of that series’ drifter protagonist, Ginko. But it’s Doctor Black Jack who most comes to mind for me, and not just because of his classy monochromatic outfit and his knack for seeing into the souls of others. What makes Decim a fascinating protagonist is that, like Black Jack, he makes mistakes.

The series began its life as “Death Billiards,” a 24-minute short produced by Studio Madhouse as part of the 2013 Young Animator Training Project. The idea was that the Japanese government would fund original anime projects that could act as catalysts for up-and-coming animators. Like Little Witch Academia, based on another short from that year’s program, much of the characterization and setting of the series was already present in the “Death Billiards” short, including the character designs and the bar’s decor.

In “Billiards,” however, the only character other than Decim and his guests is an unnamed female assistant who provides some limited commentary. In the TV series, she graduates to a central role; she serves not only as an introduction to the world of arbiters (it turns out Decim’s not the only one), but as the series’ emotional core. Under her influence, what at first appears to be an impartial arbitration begins to break down.

You see, Decim’s games don’t just force players to compete with each other; they also put them under intense pressure. In the first episode a husband and wife play darts, but the boards are linked to their organs, causing intense pain with each dart. The twist: each one’s board is linked not to their own organs, but their spouse’s (and you thought shopping at Ikea was hard on a relationship). These cruelly ironic rules are intended to bring out the “darkness in people’s hearts” so Decim can determine who is worthy and who is not, but the assistant isn’t so sure, and what makes Death Parade so satisfying is how, slowly but surely, this doubt breaks down the series’ own premise. How can an unfeeling being like Decim judge the tortured souls that walk into his bar? How can someone who’s never even lived begin to understand what it’s like to die?

This tension between the two protagonists forms the series’ central plot, which resolves by the end with an appropriately subtle emotional climax, leaving both Decim and his assistant changed ever so slightly by their experiences. For a series that could have devolved into screaming action scenes, it’s a wonderfully introspective ending.

That said, the individual episodes, which mostly focus on pairs of guests at Quindecim, sometimes do end in melodramatic tirades. By and large, however, they’re fascinating moral puzzles. A mother who stars alongside her huge family in a reality TV show faces off in an arcade game against a reclusive nerd whose parents are divorced. A young man and a detective play air hockey while Decim informs his assistant that one of them has killed someone, but he won’t tell her which one. The final judgment forms a simple but compelling hook for the end of each episode. We don’t just want to know whether each character went to heaven or hell, we want to know why. And with the added doubt that the assistant throws into the mix, Decim’s judgments take on a new dimension. Maybe it’s impossible to filter human souls into two buckets. Maybe we’re more complicated than that.

There’s been a lot of talk about a brain drain at Madhouse recently, but at least in this series from 2015, it’s hard to see much evidence of it. Decim and his assistant feature sharp, attractive, memorable designs, and the side cast looks just as great … though sometimes they look so good that it makes me wish they got more screen time. Predictably the guests don’t get quite as much love, but I appreciate the contrast between the more flashy arbiters and the realistic designs of the humans. In the more lively scenes, when characters are playing games, fighting, or going through emotional breakdowns, the animation erupts into furious, angular bursts of motion.

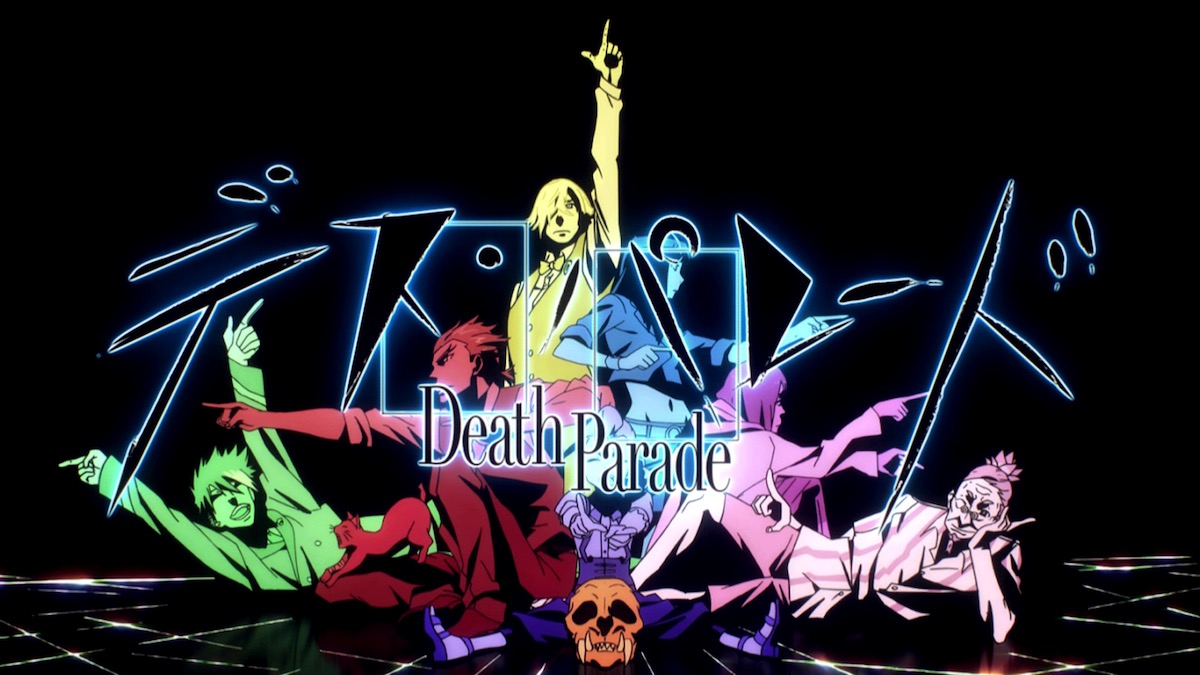

And of course, no review of Death Parade can be complete without a shoutout to its phenomenal opening sequence, directed by original creator and series director Yuzuru Tachikawa. These days he’s probably more well known for directing Mob Psycho 100, and it’s easy to see how his flamboyant style in Death Parade’s OP translated to his work on that series. While a pounding dance-rock anthem plays, the entire cast parties for a minute and a half, dancing, singing, drinking, and literally swinging from the rafters.

The intentional tonal incongruence of the OP didn’t make sense to me at first, but as I watched the series it began to come into focus, and now I see just how much it communicates the real message of Death Parade. Life is a complex thing, full of good and evil, kindness and cruelty. When it’s over, rather than brooding over its worst parts, you might as well host a big-ass party and raise a glass to life itself.