Disappearance Diary

I went to the woods because I wished to [drink] deliberately....

I jest with that subtitle; no part of Hideo Azuma’s “disappearance” is about wanting to drink. The parallel of that iconic line from Henry David Thoreau’s Walden is the degree of disconnect Azuma feels from society-at-large and his sudden need for a drastic departure from it via an immediate and outright escape. For Thoreau, this was sparked by an insurmountable curiosity bred from the monotonous boredom of the everyday. For Azuma, from his Disappearance Diary, one gets the feeling his decision to abandon all he knew was not so much a choice as it was a desperate, almost instinctual attempt to validate his own right to live after having been driven out of his own mind by oppressive obligations he could no longer live with on a mental or physical level.

I jest with that subtitle; no part of Hideo Azuma’s “disappearance” is about wanting to drink. The parallel of that iconic line from Henry David Thoreau’s Walden is the degree of disconnect Azuma feels from society-at-large and his sudden need for a drastic departure from it via an immediate and outright escape. For Thoreau, this was sparked by an insurmountable curiosity bred from the monotonous boredom of the everyday. For Azuma, from his Disappearance Diary, one gets the feeling his decision to abandon all he knew was not so much a choice as it was a desperate, almost instinctual attempt to validate his own right to live after having been driven out of his own mind by oppressive obligations he could no longer live with on a mental or physical level.

No time is wasted in getting to the essence of the experience. While Thoreau waxes philosophic for ~70 pages of pure text attempting to legitimize to the reader why he is writing about having cast off what is accepted as civilized society, Azuma, in three pages (20 panels and perhaps as many sentences), launches, with equal determination, directly into portraying his impetus; the psychological snap, which serves as the prologue, ends in Azuma’s autobiographical self, penniless and resolute, lying down on a hill with a makeshift tourniquet around his neck failing to kill himself. This moment marks the tone for this diary, while the events which follow and how they are told reveal the tale of a man of whom life is not yet ready to let go.

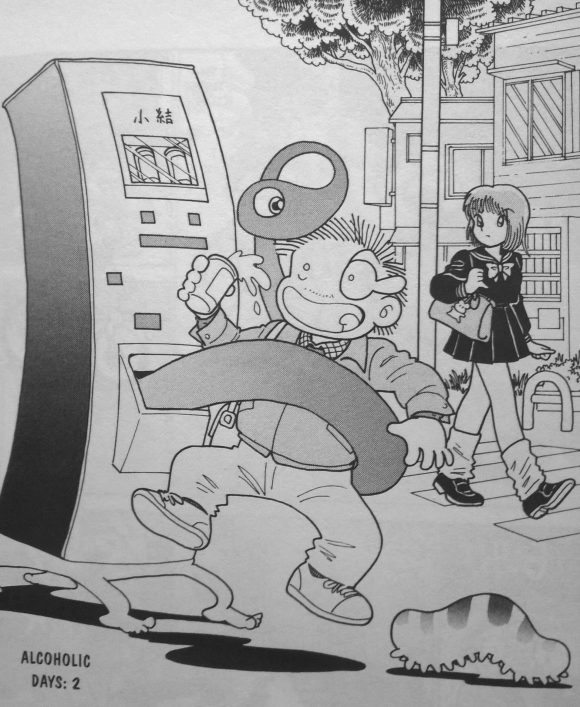

Disappearance Diary is the Superflat of manga; the story’s autobiographical content—the life and times of a manga-ka who drops everything one day and decides to become homeless—is ironically sobering given the cartoony nature of the Sunday morning funnies-esque art and buoyant narration. As the very first panel proclaims, “This manga has a positive outlook on life, and so it has been made with as much realism removed as possible.” There are three main sections to this book, and each is further divided into short, sequential tales which explore Azuma’s day-to-day life of living hand-to-mouth with a relatively passive sense of acceptance.

Disappearance Diary is the Superflat of manga; the story’s autobiographical content—the life and times of a manga-ka who drops everything one day and decides to become homeless—is ironically sobering given the cartoony nature of the Sunday morning funnies-esque art and buoyant narration. As the very first panel proclaims, “This manga has a positive outlook on life, and so it has been made with as much realism removed as possible.” There are three main sections to this book, and each is further divided into short, sequential tales which explore Azuma’s day-to-day life of living hand-to-mouth with a relatively passive sense of acceptance.

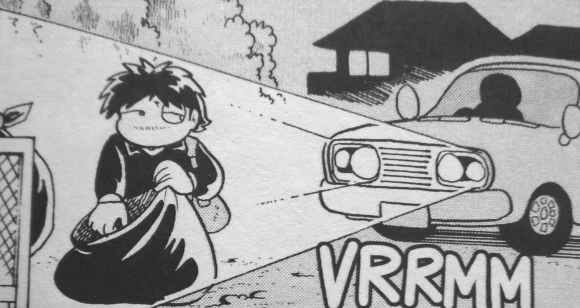

The first section, Walking at Night, depicts the process of settling into lifestyle. Driven by the most basic of needs, Azuma forages for the necessities: warmth, food, cigarettes, and booze. There’s a very subtly delivered desperation depicted despite Azuma’s rotund design. Most come when other people are around and several panels progress without narration. The absence of cheerful monolog implies self-consciousness and drives home the point what a fantasy Azuma’s acceptance of that lifestyle was while at the same time inciting sympathy within the reader by swapping an almost shameful intrigue with introspection. In short, Azuma becoming aware of his station makes readers aware of their own: that they’re reading accounts of someone else’s hard time as entertainment. But then the moment passes, and the next tale begins.

The first section, Walking at Night, depicts the process of settling into lifestyle. Driven by the most basic of needs, Azuma forages for the necessities: warmth, food, cigarettes, and booze. There’s a very subtly delivered desperation depicted despite Azuma’s rotund design. Most come when other people are around and several panels progress without narration. The absence of cheerful monolog implies self-consciousness and drives home the point what a fantasy Azuma’s acceptance of that lifestyle was while at the same time inciting sympathy within the reader by swapping an almost shameful intrigue with introspection. In short, Azuma becoming aware of his station makes readers aware of their own: that they’re reading accounts of someone else’s hard time as entertainment. But then the moment passes, and the next tale begins.

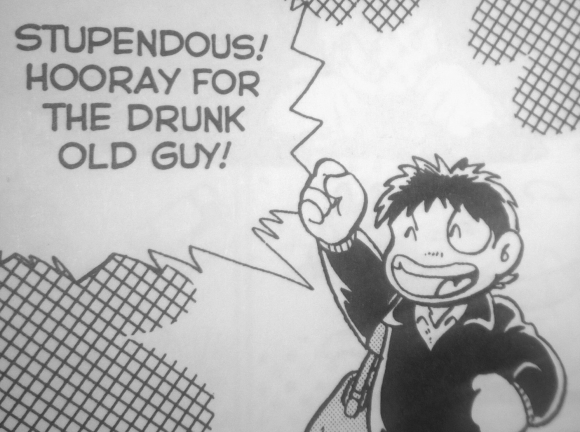

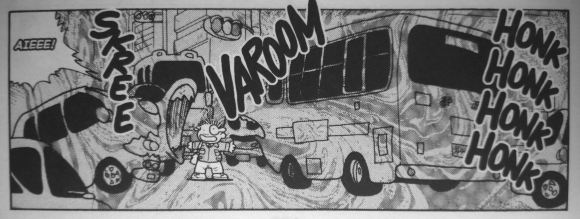

Walking Around Town, the second section, recalls Azuma’s second bout of homelessness. Things get off to a relatively smooth start since Azuma is now a seasoned veteran of bohemia, but there is also much more than scavenging in this tale. In addition to describing, at great length, his stint as a pipe layer, Azuma recounts his entry into the manga industry. There’s even a Tezuka cameo! Whereas the first section was largely introspection and Azuma working out his place in the world, the second section is a much more observation of others’ behaviors when around him. There’s a lot more outright humor in this section as opposed to the first, but since the cast is expanded exponentially, that’s not surprising. Frustration is stripped away from the act of living and applied to having to live with the presence of others.

Walking Around Town, the second section, recalls Azuma’s second bout of homelessness. Things get off to a relatively smooth start since Azuma is now a seasoned veteran of bohemia, but there is also much more than scavenging in this tale. In addition to describing, at great length, his stint as a pipe layer, Azuma recounts his entry into the manga industry. There’s even a Tezuka cameo! Whereas the first section was largely introspection and Azuma working out his place in the world, the second section is a much more observation of others’ behaviors when around him. There’s a lot more outright humor in this section as opposed to the first, but since the cast is expanded exponentially, that’s not surprising. Frustration is stripped away from the act of living and applied to having to live with the presence of others.

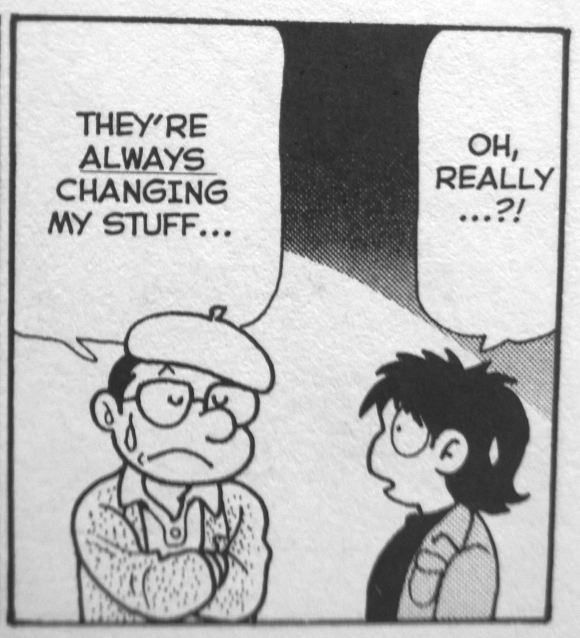

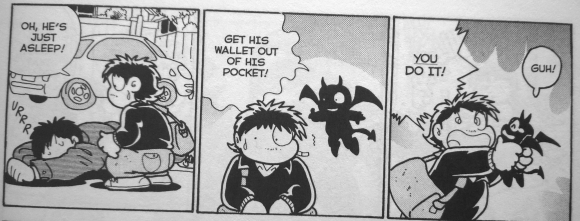

The final section, Alcoholic Ward, blends the first two sections almost too perfectly. Azuma’s back working as a manga-ka when his love for and dependency on alcohol starts to affect his work, his marriage, and his health. He’s forcefully committed to a psychiatric hospital after drinking himself to the point where he can’t ingest anything. First off, let me say Azuma’s wife must’ve been a saint to put up with not only his two disappearances but his degradation into a worthless pile of flesh. Select panels in this section have a creepy, hallucinogenic edge to them which complements Azuma’s increasing dementia and the darker subject matter at hand. While it’s a rough story to take in, there’s still a good bit of humor leveraged in relaying the situations he encountered at the hospital as well as depictions of himself and the people he met there. Also, like the pipe laying chapters, there’s a good deal of time and panel space dedicated to procedure (this time regarding hospital and AA meeting policies).

The final section, Alcoholic Ward, blends the first two sections almost too perfectly. Azuma’s back working as a manga-ka when his love for and dependency on alcohol starts to affect his work, his marriage, and his health. He’s forcefully committed to a psychiatric hospital after drinking himself to the point where he can’t ingest anything. First off, let me say Azuma’s wife must’ve been a saint to put up with not only his two disappearances but his degradation into a worthless pile of flesh. Select panels in this section have a creepy, hallucinogenic edge to them which complements Azuma’s increasing dementia and the darker subject matter at hand. While it’s a rough story to take in, there’s still a good bit of humor leveraged in relaying the situations he encountered at the hospital as well as depictions of himself and the people he met there. Also, like the pipe laying chapters, there’s a good deal of time and panel space dedicated to procedure (this time regarding hospital and AA meeting policies).

I’ve seen Disappearance Diary called a cautionary tale, and it is. What’s refreshing about the work, however, is that it’s not heavy handed. The stories and moments therein are incredibly intimate and painfully honest (even for all the censorship of realism). Even though the entire book is a reflection upon a buried and lurking sadness, Azuma manages to pull of an incredible feat in coercing a smile at every turn. But wait, there’s more. As much as this book is a warning to others, it is also an apology in the exact same manner; Azuma breaks the fourth wall in many instances within these pages—apologizing to some, thanking others, and addressing the general reader. In that fashion, I’d like to do the same.

I’ve seen Disappearance Diary called a cautionary tale, and it is. What’s refreshing about the work, however, is that it’s not heavy handed. The stories and moments therein are incredibly intimate and painfully honest (even for all the censorship of realism). Even though the entire book is a reflection upon a buried and lurking sadness, Azuma manages to pull of an incredible feat in coercing a smile at every turn. But wait, there’s more. As much as this book is a warning to others, it is also an apology in the exact same manner; Azuma breaks the fourth wall in many instances within these pages—apologizing to some, thanking others, and addressing the general reader. In that fashion, I’d like to do the same.

Alcohol is all well and good in moderation (like everything else) and can be REALLY awesome once in a while in excess, but like I’ve said since day one of this column via the disclaimer, booze is a habit-forming substance. Make sure you know yourself well enough to put the bottle down and surround yourself with those who love you enough to make you put the bottle down when you forget yourself. OR (as is the faux lesson from Disappearance Diary) don’t ever marry; wives who genuinely care about their husbands make missing persons reports to the police.

Disappearance Diary is available via FANFARE (amazon)